Heart, Soul, Mind, CuntReview of You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy IannoneKate Wolf, XTRA Magazine

reviews, 09/26/15

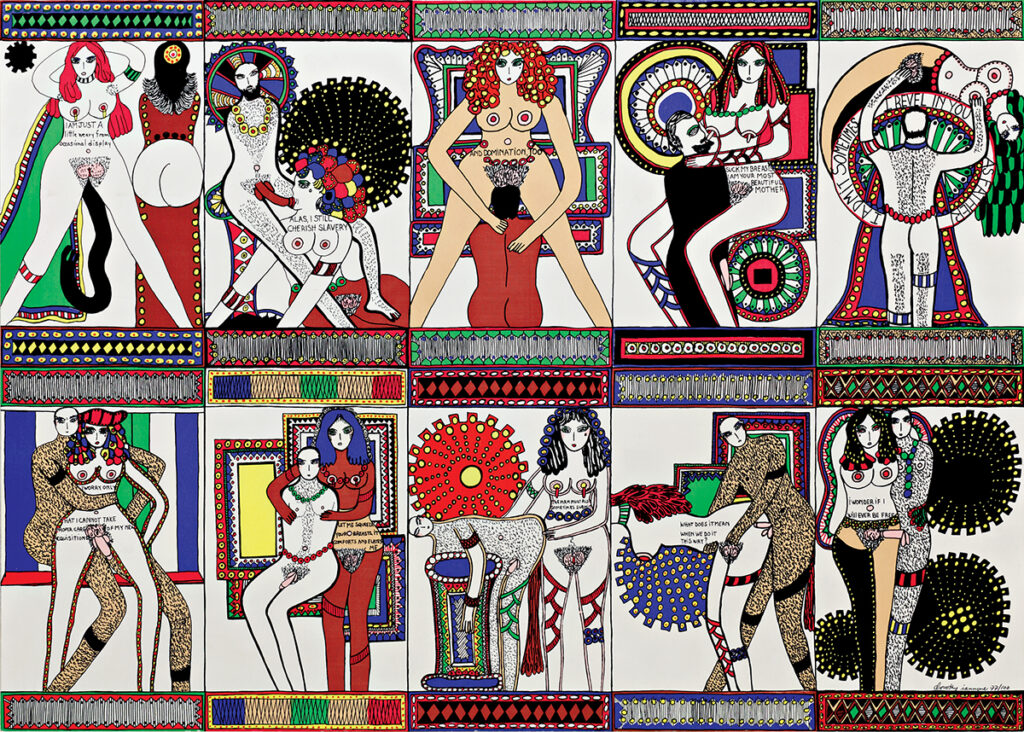

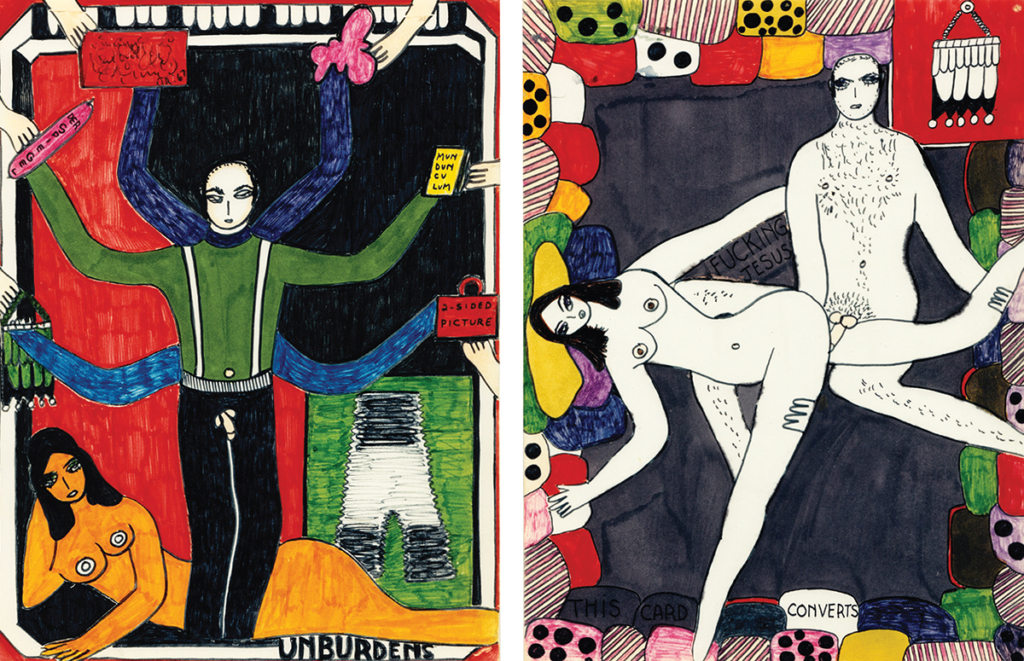

Dorothy Iannone, Ten Scenes, 1969. Color silkscreen on paper, 26.75 × 37.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Air de Paris, Paris. Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul.

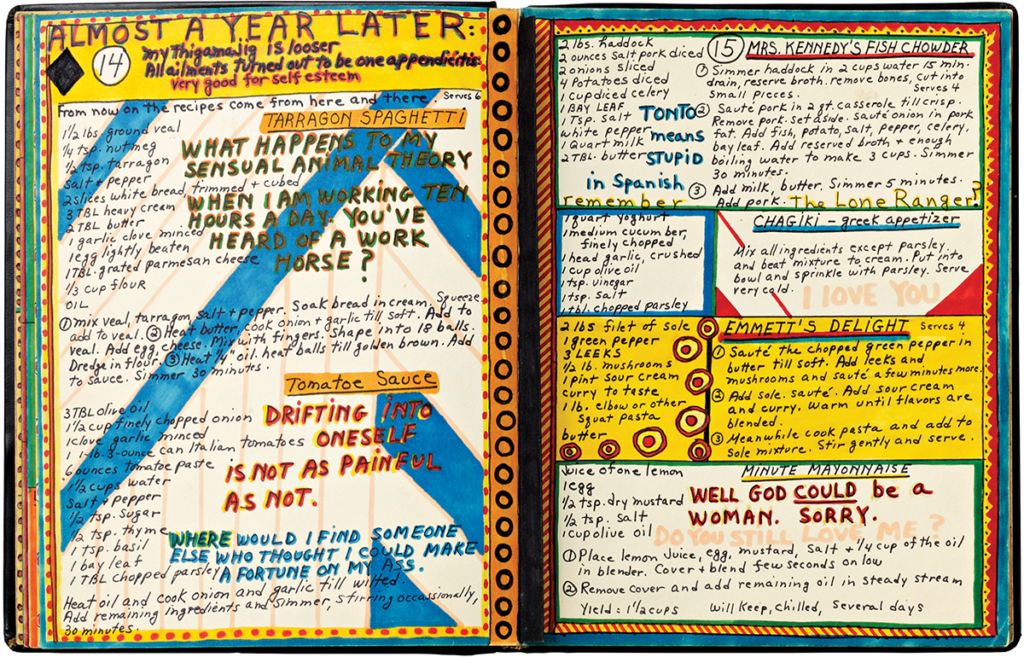

In An Icelandic Saga, a series of 48 black ink drawings on Bristol board that fluidly wed image and text, Dorothy Iannone recounts the story of her 1967 voyage to Iceland. It was there she met the artist Dieter Roth, who greeted Iannone, her then husband James Upham, and their friend, Fluxus artist and poet Emmet Williams, as their freighter docked, “WITH A VERY FRESH FISH, WRAPPED IN NEWSPAPER UNDER HIS ARM.”1 Anyone familiar with Iannone’s work, in which erotic depictions of Roth often appear, knows the auspiciousness of this encounter: within days the pair had pledged their love for one another. A week later, on the morning of her return home to New York with Upham, she confessed and bought a one-way ticket back to Reykjavik for the following day. In 1978, the same year she composed the first part of the Saga, Iannone completed another set of autobiographical drawings, L’Adorable Trixie, a timeline of personal evolution. Describing again her meeting with Roth, she writes that it was the moment when she “LEFT FOREVER THE IDEA OF HOME AND STARTED THAT LONG DESIRED JOURNEY WHICH WAS HER OWN LIFE.”2

Such a tumultuous turn of events—the dramatic break from both husband and homeland—would naturally change anyone’s life, but here the rupture is also tied to Iannone’s artistic development. She was born in Boston in 1933 and self-trained as an artist. Prior to the trip to Iceland, she had been making abstract paintings and collages in New York for more than half a decade and had transitioned to figuration shortly before leaving the United States. Most notable was an exhibition in 1967 at the Stryke Gallery, a downtown exhibition space she ran for four years with Upham, in which she showed small wood cutouts of popular figures, such as Bob Dylan, Norman Mailer, and the Kennedy family, with exposed genitals drawn on the outside of their clothes. But Iannone maintains that something powerful coalesced when she began her relationship with Roth, who was the first and most prominent of a number of muses. The work that followed—much of it portraying graphic amatory acts, with declarations of erotic devotion and happiness, as well as registers of pain and doubt often written directly onto figures’ bodies—is positioned as coming out of the revelation of a profound and liberating Eros or, as she later calls it (in a nod to mystical and Eastern philosophy), “ecstatic unity.” Even after her departure from Roth seven years later, the tenet of becoming one with another through erotic love as a form of deep spirituality, or as the meaning of art itself, would remain one of Iannone’s central themes.

An evangelist for sexual pleasure and unmitigated female sexuality, Iannone’s bold embrace of sex and love in her work is matched by an equally if not more robust drive toward narrative construction and inventive forms of autobiography. The notion of unity extends beyond pictorial representations of the fusing of lovers’ bodies to a yoking together of disparate points in time and place, truth and fiction, people and identities, as well as a compositional cohesion. One could be excused for occasionally confusing her art and her life, because at times she seems to purposely collide the two. At the same time, she consciously plays with persona, elision, pun, and self-reference, always asserting her role (often with humor) as the interlocutor between her experience and its application.

An Icelandic Saga—which opens Siglio Press’s recent volume of selections from 40 years’ worth of Iannone’s drawings, paintings, artist books, etchings, and writings, and is organized in two parts around a loose chronology of Iannone’s life with Roth and after—quickly becomes a mise-en-abyme. A two-page interlude deposited early in the work locates the artist in her Berlin apartment long after her trip, writing and drawing the text and image that her “dear and loyal” reader is now viewing. The interjection introduces another layer of time to the story being told. Afterwards, Iannone periodically alternates between past and present, as well as different points of view. This shifting occurs in both image and language, as in one drawing, where in a rounded, even cursive she describes a night of drinking on the freighter when Emmet Williams impishly burned a dollar bill, which enraged the wealthy Upham. Everything is written in first person, until the last line, where she describes resignedly following Upham out of the ship’s bar after he’s returned for her a second time: “James expected me to follow and a few minutes later he returned and asked his wife, once more, to follow him. Reluctantly she did.”3

While she often writes about herself as a character, the sudden change in perspective foregrounds this construction, concisely expressing the gap between her role as the dutiful wife and the liberated woman crafting her experience into art. This sense is given dimension and echoed by the drawings that border and break up the text. Iannone depicts herself sitting nude at a desk, perhaps completing or beginning another artwork: a page bearing the name of the German journal where An Icelandic Saga was first published, Sondern, rests on the table with a message inscribed to a new lover, “Danton,” dated to the present year of 1978. A large, shadowy hand bridges the distance to a masked male nude with an erect penis across the page wearing a cape and a crown of rosettes, which also border the desk and appear in between the fingers of the hand; they morph to become the pattern on the cape, cling to the top of the black outline framing the drawing and reappear many times again as a motif throughout the work.

- 1. Dorothy Iannone, You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, ed. Lisa Pearson (Los Angeles: Siglio Press, 2014), 29. 2. Ibid., 221. 3. Ibid., 27.

- Ibid., 221.

- Ibid., 27.

Continue reading at XTRA.

see also

Books

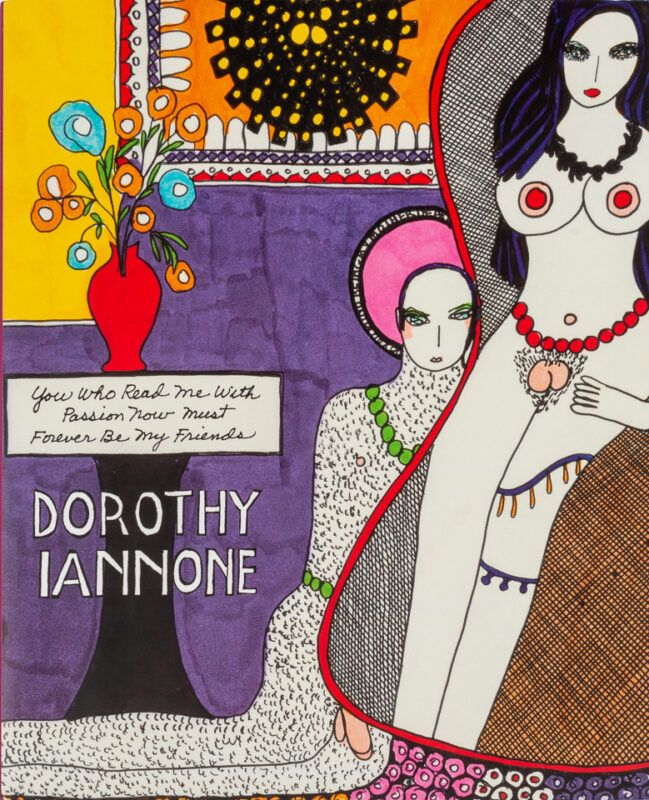

You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My FriendsEdited by Lisa Pearson with an essay by Trinie Dalton

Books

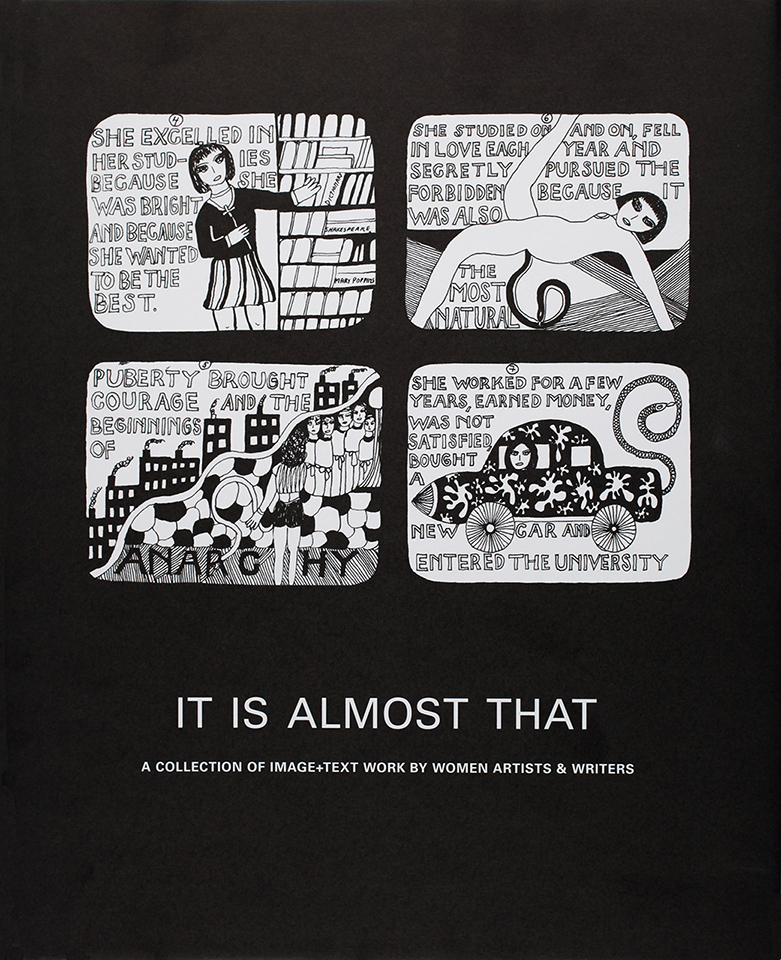

It Is Almost ThatA Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers

Excerpts

“Culminations” (excerpt)Trinie Dalton

Excerpts

Editor’s Note: Dorothy Iannone CompendiumLisa Pearson

✼ elsewhere:

“Not an object or a text but a name, a spirit: Jean Brown … The name ‘Jean Brown’ itself was, for me, the conduit of Howe’s “mystic, documentary telepathy.” When her name appeared on a citation, I sensed that this object or book had been carefully selected, cared for, considered, held.”

[...]