“Culminations” (excerpt)Trinie Dalton

excerpts, 11/01/14

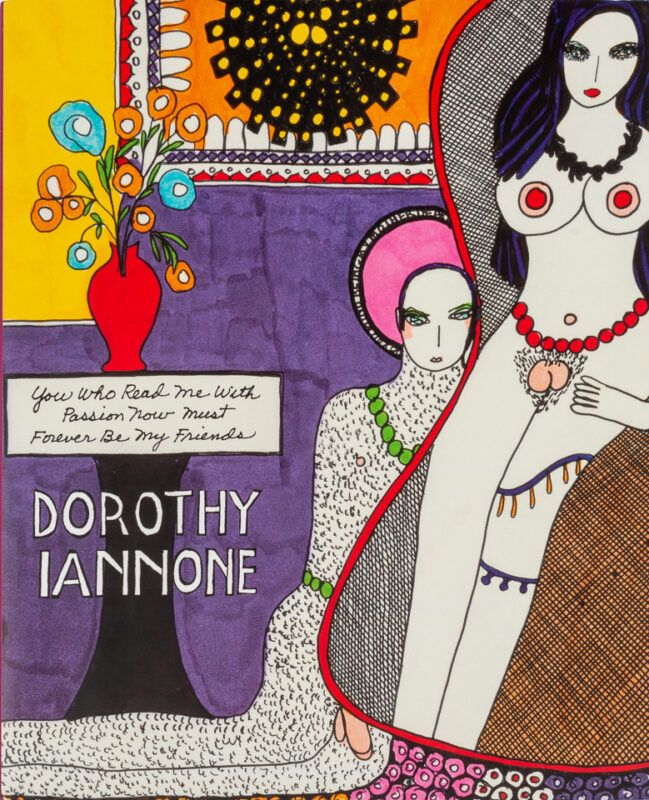

Published in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy Iannone, edited by Lisa Pearson, Siglio, 2014. All rights reserved. © 2014 Trinie Dalton.

III.

Dorothy says that she often considers figuration a crucial part of her textual arrangement and in that, she pencils everything out then allows “the eraser [to be her] best friend.” Her compositions are intricately planned, but once started, she lets their contours inform the story; in this way, she says that she cannot make a mistake. “I judge it aesthetically, with no regrets,” she says. “It was the best I could do at the time.” Therefore, her texts are matter, fixed in space by time; they aren’t in opposition to or in competition with the visual, pictorial components but are integral: first, as elements in the picture plane that seek to more significantly connect the artist to the viewer, and secondly, as generous clues to her visual acuity. Like painting studies, the anecdotal, text-based elements reveal source material, initial gestures and sensibilities, observations and psychological interests predicting imagery that position reading as a synaesthetic, physical viewing experience. Again and again, Dorothy refers to her stories as art, does not distinguish between textual and visual narrativity, rather says all creative practice propels the artist into a unified exploration. Her artwork, then, can and should be “read.” Often, statements affirming this notion of unified narrativities are written in all-caps.

ART IS THE WORLD I HAVE CREATED WHICH NEVER LETS ME DOWN, A WORLD TO WHICH I CAN RETURN AGAIN AND AGAIN AND SMILE AND BE IMMORTAL.17

ON THE CONTINUING JOURNEY TOWARDS A SHORE WHOSE DISTANCE SOMETIMES SEEMS EVEN TO INCREASE + NOW, FULLY AWARE THAT THE WAY MUST CERTAINLY BE A SOLITARY ONE, I SIGH + WONDER IF I WILL EVER MOVE FROM THE VIEW IN WHICH I FIND MYSELF TODAY. BUT NOT TO GO ON NOW IS DEATH.18

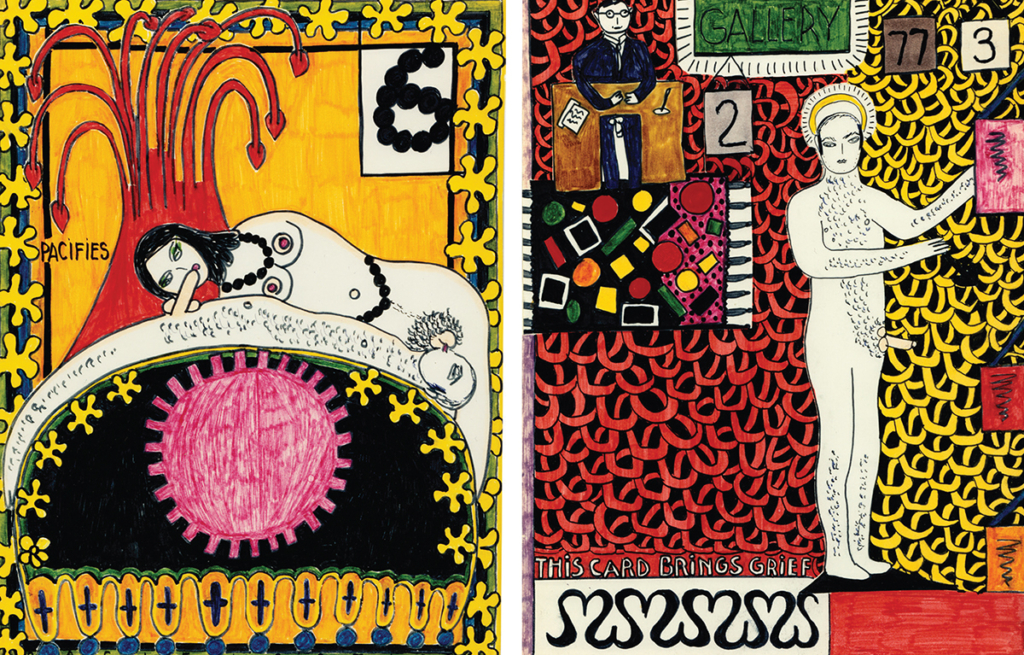

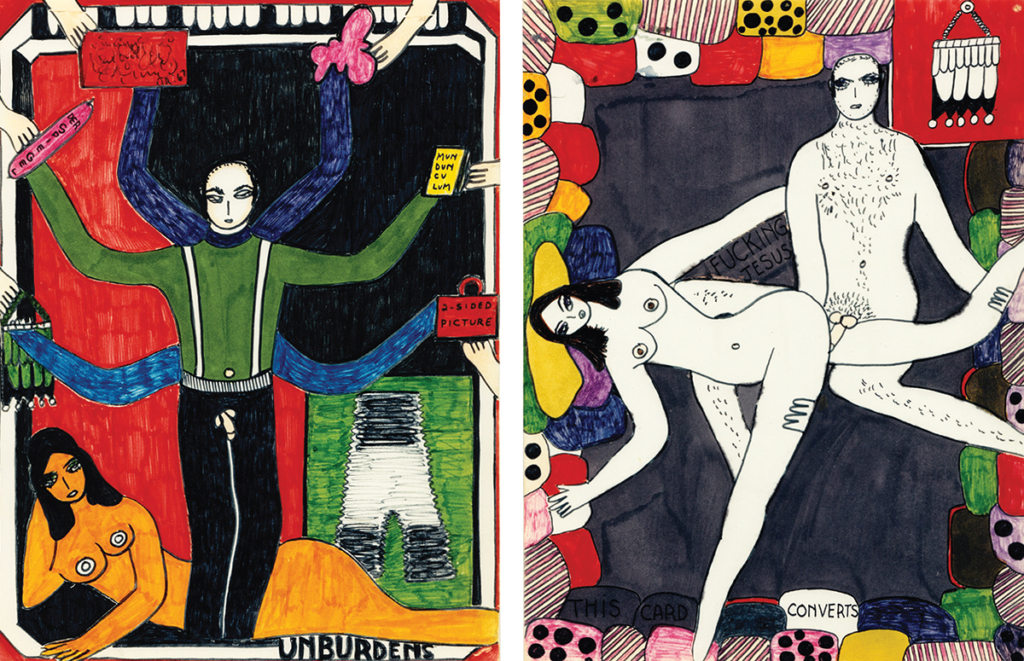

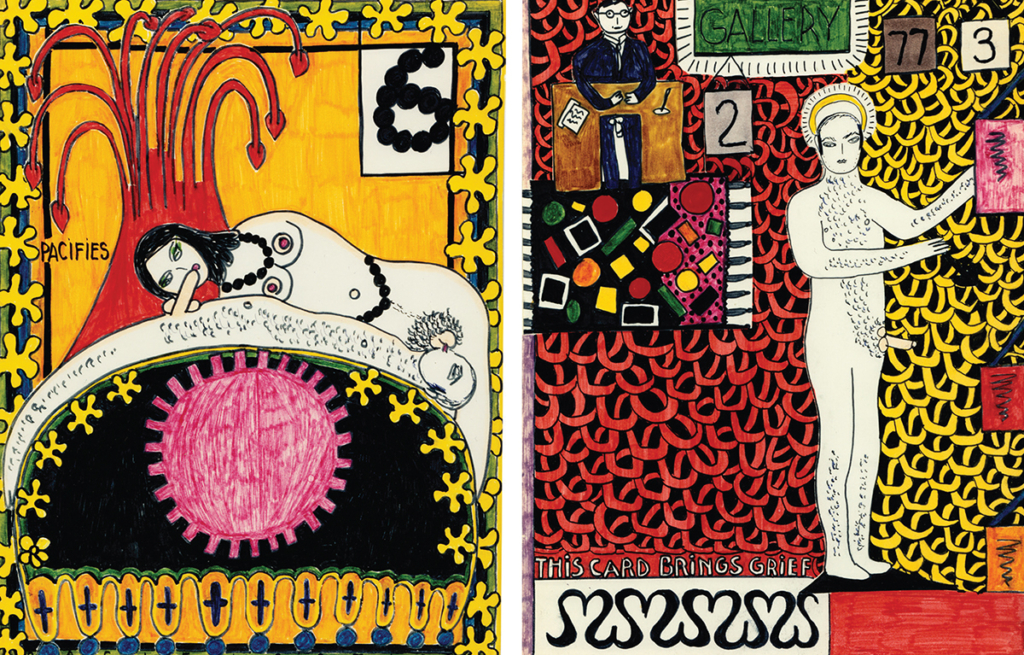

While some of the language in this book exists purely as text to be read, these texts above removed from their pictorial context, lose something. Dorothy’s typography varies widely, the letters themselves evoking beadwork, woodcraft, wobbly cursive a ghost might write in dust, telephone cordage, illuminated manuscripts, coiled rope, tattooing, tendrils and vines; it sometimes grounds her figures against a background, like wallpaper, or it appears as signage, or it even sometimes acts as umbilical lifelines on the page as it literally “draws” characters together in the compositions. More emphatic messages might be in bold, or larger in scale than figurative elements or interior thoughts conveyed in smaller script across the same image. On occasion, text and image are separated, placed across from each other in a book spread (Danger In Düsseldorf), or on multiple sides of 3D projects. Her liberal application of hand lettering around her figures is what, in part, gives her artwork an ornamental sensibility, but two major factors distinguish her lettering from sheer unadulterated ornamentation. First, ornaments are elements that can be removed, while the object they’re adorning “remains structurally intact, recognizable, and can still perform its function.”19 Secondly, “ornament is decoration in which the visual pleasure of form significantly outweighs the communicative value of content.”20

Neither definition suits Dorothy’s typography, which is a primary component in the compositions and not only invites reading for content but cues the reader in to mood and tone of the content expressed. The way she establishes handwriting and figuration as equal partners in a communicative system reminds me not only of likhiya but also of medieval Japanese image/text traditions like haiga—pictorial haiku painting—and again, emaki, a yamato-e (picture-scroll) style that “illustrates, usually with accompanying text, literary works, moral tales, biographies, and legends concerning the origin of celebrated shrines and temples.”21 Her writing invokes reverie in the making—laboriously spelling out every word, in pencil then in ink, a commitment of each sentiment expressed twice to memory. Her writing becomes her, is textile, lyric, part of her body’s tissue as much as it is a material constituent in her artworks. The carefully designed, slow rendering of the text commits it to the artist’s memory, as I mentioned in the opening, an act of live revision like the variants in Emily Dickinson’s “scraps,” though poet/artist Jen Bervin corrects that word to call them “a sort of small fabric” in her and Marta Werner’s art book facsimile of Dickinson’s envelope poems, The Gorgeous Nothings.22

Dorothy considers the handwriting on her artworks a “compositional decision,” central to the conveyance of her message in each piece, of course, but hand-lettering is also part of a physical challenge that keeps her in an active, meditative state of “practice” and that formally moves her to the satisfaction she finds in finishing an artwork: she says, “the moment of fulfillment must have a deep influence on your body/mind.” Paradoxically, while Dorothy’s artworks acquire a highly finished look, in that their compositions are nearly hermetically sealed by border designs, as well as additive, repeating, and hypotactic patterning, her artworks obliterate my sense of linear time—the artwork’s narrative is always conceiving, always finishing, like an ouroboros. The way she revises, retells, reimagines stories (the “Follow Me” manifestos; or falling in love with Dieter reconfigured from An Icelandic Saga into the story of Otto and Anna in Danger in Düsseldorf), as well as the way her own hand is apparent in each gesture belies her artwork’s prismatic circuitry; one can understand through multiple sensory depictions of an instant moment a wider spectrum of time, as well as how that particular point in time influences the present. A Cookbook exemplifies this, as its recipes are bifurcated by the chef’s interior thoughts on the page, artfully arranged in larger lettering that is frequently highlighted with red or green felt pen.

DRIFTING INTO ONESELF IS NOT AS PAINFUL AS NOT. (Accompanies “Tomato Sauce”)

WELL GOD COULD BE A WOMAN. SORRY. DO YOU STILL LOVE ME? (Accompanies “Minute Mayonnaise”)

THE WOMEN’S LIBERATION MOVEMENT PROVED THEIR WORTH WHEN THEY POINTED OUT TO THE LADIES THAT THE VAGINAL DEODORANT WAS AN INSULT. (Accompanies “Baked Red Snapper with Grapefruit”)

This multi-layering of time also mirrors two primary functions of haiga and emaki: to bring the past into the present through storytelling and poetry and to invite the artist into a state of meditative clarity during creation which, if the picture/poem is successful, will invite the viewer into a similar presence of mind. This idea of mindfulness may be connected to Dorothy’s Tibetan Buddhist practice.23 It is evident to me that she experiences autobiography not as a set of past events to romanticize but as inspiring seedling episodes for stories (whether expressed visually or textually) that are elliptical, recurring and interrelated, forever relevant.

The ways Dorothy utilizes autobiography, as well as how she formally expresses these notions through her inextricable weave of text and image, further embodies her concept of ecstatic unity. If her concept of ecstatic unity is seen as merely sexual, then one cannot see that it also refers to the unity of self, an acceptance and joy found in individualism which evolves in her work over time. A purely sexual reading also awards primacy to the male notion of finishing, i.e. the orgasm, which implicates physical climax as the end-goal, and that is certainly not Dorothy’s intention. Rather, when one considers how evocations of non-linear time can be embedded into an artwork, and how autobiography has the ability to invoke the past, suddenly autobiography is the perfect aesthetic tool and material, just as the way Dorothy’s ancient/classical ornamentation and figuration ironically lends her artwork contemporary relevance. Her hand-lettered pictures transgress notions of linearity and the idea of a finishing point, while her concept of art as working practice towards lucid mindfulness is another way of defining ecstatic unity.

Dorothy says that remaking or remodeling her autobiography as material allows her into “a space of less embarrassment,” or invites a “selection” process to undercut the intimidation that can come while staring at a blank canvas or paper. Her autobiography, then, is a shifting poetic as well as a narrative constraint that helps her yield unexpected material from events in her daily life. For example, her “Dialogues” (I, IV, IX and the unnumbered work included in this book) then become much more than Kama Sutra-esque studies of Dorothy and Roth in various sexual positions and instead read as role-playing conversations that explore power dynamics:

MOVE OVER/NO

PUT OUT THE LIGHT/ I CAN’T IT’S ON YOUR SIDE

I AM NOT D./WHO ARE YOU THEN?

“Soon after Dieter and I started living together,” Dorothy has said, “I made books which I called ‘Dialogues’ where my ‘People’ turned into the two of us, and instead of taking my texts from literature as I had been doing in some of my paintings, I now used the words that Dieter and I had spoken.”24 While her relationship with Dieter Roth has been heavily documented, it is fitting for this book to begin with An Icelandic Saga because, while it locates Roth as muse and provocateur (among others who populate her work in general), it mostly illustrates Dorothy’s mutating definitions of autobiography and its usage, archetypally proving how no story of Dorothy’s has a single, simple subject matter. All of her stories do pay tribute to her source inspiration, often a lover or friend, but they are not mere hero-worship. Of An Icelandic Saga, a pictorial origin story about personal transformation, adventure, dedicated passion, and much more, Dorothy says she does not consider her practice one of mythologizing, save the accidental mythic in An Icelandic Saga, in which she “scrupulously chose decisive moments.” “In retrospect,” she says, remembering specifically the mermaid/fish imagery, “I chose moments that trigger deep memory. Primordial moments which hold the greatest mysteries. The mythical, biblical or primordial moments put together into an original voice is what makes [An Icelandic Saga] art.” Her employment of the word “art” there implies a culmination of narrative and visual factors, efforts and effects that create whole arrangements committing, above all, to a chronicle of pinnacle moments that demarcate her flexible, roving search for beauty—an artistic reflection of Dorothy’s education, to borrow Elaine Scarry’s definition of education:

The willingness to continually revise one’s own location in order to place oneself in the path of beauty is the basic impulse underlying education. One submits oneself to other minds (teachers) in order to increase the chance that one will be looking in the right direction when a comet makes a sweep through a certain patch of sky. The arts and sciences, like Plato’s dialogues, have at their center the drive to confer greater clarity on what already has clear discernability, as well as to confer initial clarity on what originally has none.25

Dorothy’s definitions of ecstatic unity are close to my definitions of beauty. While I’ve attempted here to interpret her multiple expressions of this unity, one perhaps most readily expresses the connectivity she seeks: unification between the artist and the reader/viewer as mentioned in the essay’s opening. This obliteration of boundaries between Making and Experiencing the object or text is phenomenologically transgressive, and it is what originally attracted me to Dorothy’s artwork. For example, I adore the following moment in An Icelandic Saga that acknowledges the intimacy of the reader/viewer’s gaze. A line drawing bisects the page, showing Dorothy reclining in a bed covered with intricately rendered rosetted and striped textiles. Since the narrator is depicted nude, her body’s surface is an all-white space; the highly ornamented density of black marks on the bedding contrasts her white body, illuminating it, thereby drawing the eye inside that white space directly to the title of the book she’s reading, Genius and Lust: Mailer on Miller. Elements circulate as in a graphic novel: the textual content first invites the eye to view the picture, the picture then invites the eye back into narrative with its highlighted depiction of a specifically titled book. From there the reasoning for the depiction of the book is explained through hand-lettered all-caps text below the picture:

I HAVE BEEN UP SINCE MIDNIGHT READING NORMAN MAILER ON HENRY MILLER, MARVELING HOW OUR LIVES HAVE TOUCHED AND HOW WE HAVE, IN ONE WAY OR ANOTHER, RECOGNIZED EACH OTHER.

“Our” unity between Mailer, Miller, the artist and the reader/viewer is underscored when one realizes a secondary message only available through reading:

YOU WHO READ ME WITH PASSION NOW MUST FOREVER BE MY FRIENDS.

Dorothy’s artwork will endure because she has obliterated practically every type of separation categorically, in both textual and material realms; her artwork has contemporary edging but its scope surpasses artwork that deals in strictly contemporary art historical discourse. This is her artwork’s great aesthetic strength, fortified through her personal endurance and tenacity. Dorothy’s efforts to evolve her artwork’s message through audacious usages of timeless content and imagery reflect constant attention and energy, an inquisitive desire to push both forwards and backwards in every letter, story, brushstroke, pencil mark, sweep of color. Above all, this is a body of ecstatic artwork that always revels in the “going on,” the “telling.”

SO YOU SEE, STRICTLY SPEAKING, THERE NEED BE NO SEPARATION BETWEEN EATING AND MEDITATION, OR ANYTHING ELSE AT ALL—INCLUDING SLEEPING—AND MEDITATION. TO BE AWARE TO THIS DEGREE, OF COURSE, TAKES A LOT OF PRACTICE (AND OPEN-HEARTEDNESS TOO). NEEDLESS TO SAY I’M JUST A BEGINNER BUT IF YOU’D LIKE TO HEAR A LITTLE MORE ABOUT PRACTICING WHILE ENJOYING YOUR SUCCULENT DUCK, I’D LIKE TO GO ON TELLING YOU.26

footnotes

- Dorothy Iannone, “An Icelandic Saga,” in this edition, 23.

- Dorothy Iannone, “Position Report #4: On The Continuing Journey,” in this edition, 289.

- Trilling, Ornament, 3.

- ibid.

- Okudaira, Emaki, 11.

- Jen Bervin and Marta Werner, Emily Dickinson: The Gorgeous Nothings (New York: New Directions Press/Christine Burgin, 2013), 8.

- Noa Jones, “Interview with Dorothy Iannone,” Tricycle, Spring 2013.

- Dorothy Iannone, email correspondence with author, 2014.

- Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and Being Just, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 8.

- Dorothy Iannone, “To Emmett, Who Hasn’t Changed A Bit,” in this edition, 281.

see also

Books

You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My FriendsEdited by Lisa Pearson with an essay by Trinie Dalton

Reviews

Heart, Soul, Mind, CuntReview of You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy IannoneKate Wolf, XTRA Magazine

Excerpts

Editor’s Note: Dorothy Iannone CompendiumLisa Pearson

Excerpts

Dorothy Iannone, a short biographyLisa Pearson

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

October 25, 2022 — In the rearview mirror: I Will Keep My Soul has gone on press, the new website is launched, NY Art Book Fair hurricane has subsided. Now—finally—looking toward the horizon which happens, at this very moment, to be the blue on blue of California sky and Pacific ocean. But returning to the melancholia of fall and coming days of gray to read, read, read.

[...]