Editor’s Note: Dorothy Iannone CompendiumLisa Pearson

excerpts, 10/31/14

Published in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy Iannone, edited by Lisa Pearson. All rights reserved. © 2014 Lisa Pearson and Siglio Press.

Ask Dorothy for the human touch (lost in art).

—Ben Vautier

In An Icelandic Saga, the work that opens part one of this book, Dorothy Iannone narrates an extraordinary journey—on a freighter across an ocean from New York to Reykjavík, Iceland, from a somewhat conventional marriage into a love affair marked by its erotic candor and emotional tumult, from a life of creature comforts to one of sexual and artistic liberation and ultimately the sacrifices made for that freedom. While Iannone had begun making art several years before An Icelandic Saga begins in 1967, it is nevertheless a kind of creation myth (though a great deal of its charm emanates from Iannone’s delight in listing and detailing the very mundane necessities of mortal life). This origin story of her life as an artist also chronicles the beginning of her search for what Iannone calls “ecstatic unity”: a search that traverses the carnal, the emotional and the spiritual, a search that embraces transgression and contradiction, that experiments with the assertion and surrender of power, that is first driven by urgent sexual desire and then ultimately inspired by a contemplative and open embrace of self and friends, life and loss.

Frequently, Iannone addresses the reader directly in An Icelandic Saga, referring to herself most often in the third person as if privy to the past, bearing witness to it, from the sunny (and wiser) purview of her apartment in Berlin many years later. Thus the reader seems to be with her in the present moment, as a confidant, an intimate. She says to us quite early on: “you who read me with passion now must forever be my friends.” We are invited into a relationship with her and offered unconditional trust. We, as readers, are invoked, made visible, and thus there is another kind of unity in our participation, in sharing this immersive space. On the last page of An Icelandic Saga, the narrator who observes Dorothy (and is sharing Dorothy’s story with us) becomes Dorothy when Dieter Roth (the artist for whom she has left her husband) opens the door to her. This shift from third person to first person signals Iannone’s own entry into her story, taking the reader by the hand, hence the title of this book: You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends. By opening this book with An Icelandic Saga and through the sequence of works that follows, I hope the reader sees the entire collection as a subversive kind of bildungsroman: Iannone, goes out into the world (though she is already well-traveled), a seeker with eyes newly opened (though she is thirty-three at the time), as if to come into her own and realize her place in society (though she is constantly redefining the possibilities of what that place might be—as a woman, artist, lover and friend). But instead of ultimately “maturing” and learning some kind of moral lesson to live by, Iannone resists every kind of expectation with joyful gusto, disobeys every authority (except those she gleefully submits to), redefines her place in the world by creating an ever-expanding field of possibilities in that world—possibilities that arise as she turns everything inside out.

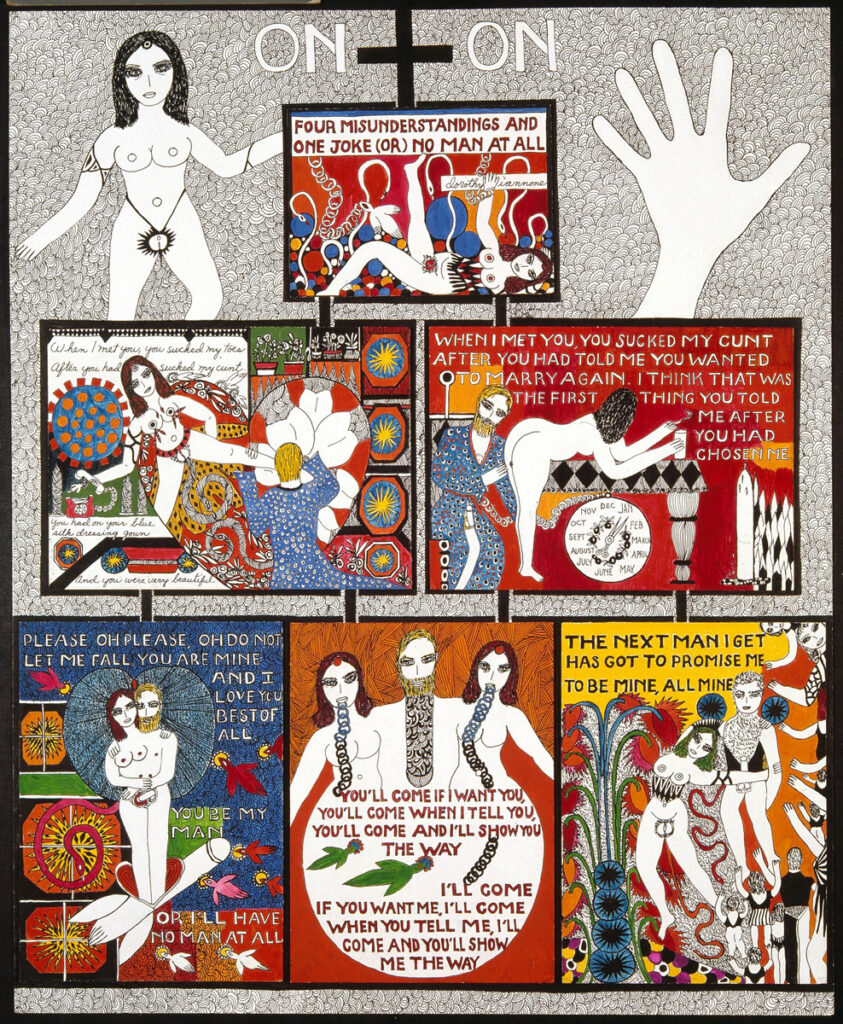

These reversals abound in Iannone’s work, whether through inversion (and merging) of male and female, muse and maker, sacred and profane, celestial and carnal, submission and dominance, compliment and insult, humor and earnestness. Nothing is quite as it seems, or wholly one thing or another. (Every one of these inversions is enlivened in the fever dream of Danger in Düsseldorf [Or] I Am Not What I Seem, a masterwork in Iannone’s oeuvre.) Her first person declarations have mutable authorship: her own voice may instead (or also, simultaneously) be that of her lover’s. The fluidity (or dissolution) between opposites is most prominently displayed in the merging of genitalia, which Iannone describes (in her interview with Trinie Dalton at the end of this book) as representing “two beings coming together spiritually through erotic love—realizing a sense of completion.” This itself is a kind of resistance, not only to traditional gender roles and sexual typecasting but also to the second-wave feminist mission of individual liberation and equality. For Iannone, in her earlier work, the pursuit of ecstatic unity through sexual union was a means (if not an explicit goal) to liberating consciousness. Iannone is willing to submit (so long as her lover is willing to submit, too) and this itself is yet another surprising inversion, here of the female medieval mystics whose chaste “marriages” to god often entailed extraordinary sexual ardor as well as self-realization through a self-denial: “That I love you passionately comes from my nature, for I am love itself. That I love you often comes from my desire, for I desire to be loved passionately. That I love you long comes from being eternal, for I am without an end and without a beginning” (Mechthild of Magdeburg, The Flowing Light of the Godhead, edited by Frank Tobin, [New York: Paulist Press, 1998], 52).

“On+On,” 1979 by Dorothy Iannone, in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, Siglio, 2014.

The complexities of submission and dominance in even the most sexually graphic aspects of Iannone’s work have much more in common with medieval mystics like Mechthild of Magdeburg than say with the narrator of Pauline Reáge’s Story of O. In the latter, the narrator tells the story of a woman who submits so completely to her lover that she becomes a slave, branded even, and abused at will. Told in third person, from the limited and almost disembodied perspective of O, the story has unrelenting sexual detail, a discomfiting experience of terror and arousal, as if Reáge is implicating the reader for her complicity in the world that will keep women as sexual chattel: eroticism as a means to political critique (I realize many read it as a classic “bondage and discipline” text in which the degradation itself is sexy, but I’d argue—elsewhere—that Story of O is feminist). In Iannone’s work, in the piece The Whip for example, the woman willingly yields: “Can you take more blows tonight? / Yes. / I mean the whip.” But Iannone also writes a little later, “I believe that the alliance between us unfolds the nature of ourselves. I believe that the emperor, my master, is not a little moved by my faith in him.” Her power (inextricably linked to the power of the beloved/the master) resides in the pleasure she takes (he gives), the faith she extends (he inspires), the dissolving of constructs, the surrender of self (as well as the assertion of self and frequent deployment of humor—something not necessarily found in the mystical texts). She writes in the postscript to The Whip (which follows a conversation between Isis and Jesus!):

“And would you consider, Sir, that the only way to move toward this modest beatitude—the eternal yes—is to consciously, hospitably, alarmingly, and diurnally shed an infinitesimal number of our infinite masks, because, Sir, one mask, forever fixed, cannot indefinitely hold the attention of the growing spirits who have, Sir, their eyes directed toward the inexhaustible.”

That, in fact, the recipient of the blows in The Whip might very well be the emperor himself becomes a distinct possibility, and the extraordinary complications of that possible reversal is echoed in Mechthild of Magdeburg, speaking—it seems—as worshiper in the voice of the worshiped: “That I hunted you was my fancy. That I captured you was my desire. That I bound you made me happy. When I wounded you, you were joined to me” (Magdeburg, 42). Throughout Iannone’s work, such inversions ultimately point to the ineffable, with an implicit affinity for Tantric metaphysics. She writes inside hearts adorning the primeval, paradisaical couple in “Flora and Fauna” (page 81): “Is not the opposite of all I say also true? I am dangerous.”

• • •

The selection and sequencing of the works for You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends was shaped by two editorial criteria: first, to trace the narrative arc of Iannone’s pursuit for ecstatic unity across the universe of her work (and life), and secondly, to offer an opportunity for the reader—who is so often lovingly invoked—to delve into her inimitable, hybrid form of image and text and read an ever-shifting field of autobiography, anecdote, allegory, song, dreamscape and fiction. This collection of diverse works from several decades—artist’s books, drawings, paintings, etchings, and writings—is sequenced “to make sense” in terms of narrative structure rather than serve a strict chronology: part one begins with Iannone meeting Dieter Roth in Iceland; in part two, after she has left Roth, Iannone searches all corners of her life for connection, revelation and fulfillment. Within this arc, I hope the reader finds thought-provoking juxtapositions, slippages, and connective tissue between the works as they accumulate.

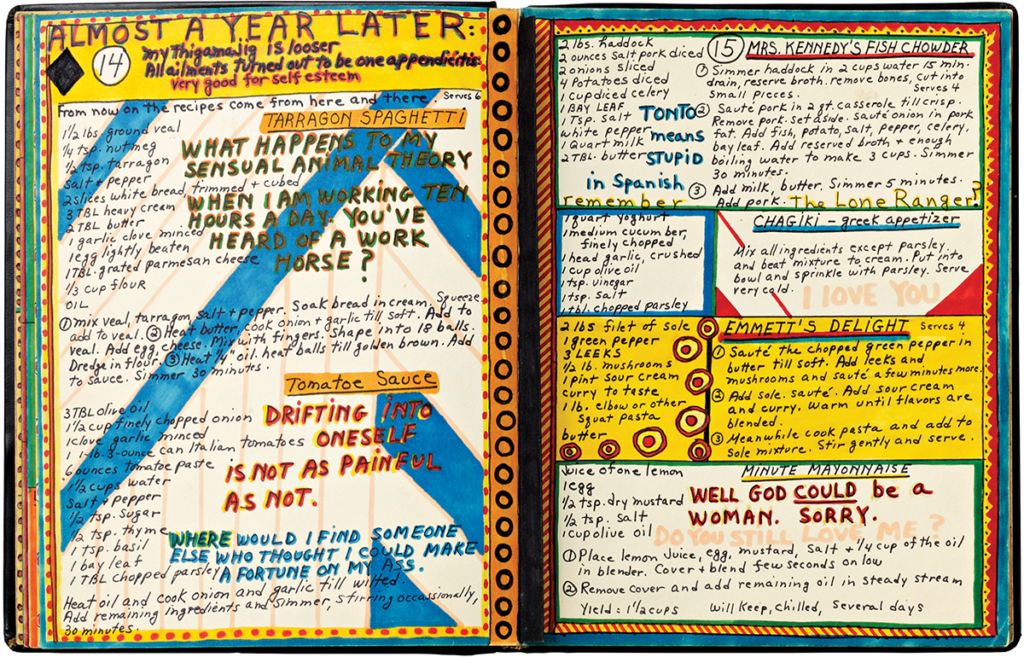

There is, in this extremely visual selection, so much to read, not simply because Iannone uses text, but also because she takes the stuff of everyday life and invests it with emotional as well as philosphical complexity. One can literally read between the lines in A Cookbook, but figuratively as well, as Iannone always seems to be revising (see the declaratives of the “Eros” paintings on page 9 and the interrogatives of “Ten Scenes” on pages 126-127, for example) as well as reasserting propositions/motifs in new contexts (a dish of duck takes on various meanings throughout). This is also why I chose to reproduce so many of the works in their entirety (e.g. Danger in Düsseldorf, An Explosive Interlude, An Icelandic Saga, the Dialogues, The Whip, Lists IV, Pieces in Autumn) or to excerpt them substantially (particularly A Cookbook, The Berlin Beauties, [Ta]rot Pack and the 75 Uncomplimentary Cards, 75 Apologies, 75 Complimentary Cards). As most of Iannone’s artist’s books are so rare and many of her drawings and paintings are multi-paged or multi-paneled (and thus rarely reproduced in full or legibly), I felt very strongly that Iannone’s work cannot be truly experienced, understood and appreciated until it has actually been thoroughly read. And since Iannone’s work has been roundly ignored for many years, if not outright censored on particular occasions, this book has at its heart a simple intention: to make a real space for her work to be read—and thus fully engaged.

That said, You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends is by no means complete. There were several works and series for which there was just no more room in the book and many narrative threads which are present but underdeveloped within the editorial scope here. Iannone’s own narrative constructions are often permeable with literary texts, poems, and filmic narratives that contend with the vast subject of love and refract Iannone’s concerns in radiant ways—in the beginning when she integrated appropriated texts from the likes of Wallace Stevens, William Butler Yeats and Gerard Manley Hopkins into her early abstract works; later in her figurative paintings, prints and drawings inspired by Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Robert Graves’s The White Goddess, among others; and most recently in her latest series, cutout sculptures called “Movie People” (see pages 5 and 6) in which she distills the love stories of films in her own voice accompanied by iconic and erotic images. Many of the works not reproduced here fortunately appear in recent museum catalogs.

The topic of censorship is another thread which Iannone addresses in Censorship And The Irrepressible Drive Toward Love And Divinity (represented here by a short text excerpt) and in The Story of Bern which Trinie Dalton discusses in her essay with an accompanying illustration. The latter chronicles “The Friends’ Show” in 1969 at the Kunsthalle in Bern, Switzerland in which invited artists were then asked to invite their own friends to participate. Dieter Roth invited Dorothy whose works (the Dialogues and [Ta]rot Pack) were the subject of the controversy that unfolds in The Story of Bern. What also emerges in The Story of Bern is a picture of a time and place, a circle of friends, almost all of whom were part of Fluxus with which Roth is often associated. While Iannone’s work manifests quite differently aesthetically and materially, friends such as Emmett Williams, Robert Filliou, Ben Vautier and George Brecht nevertheless recognized the Fluxus spirit in her work: the anarchic, the contrary, the extraordinary possibility in the quotidian, the embrace of “intermedia” and the ever-flowing confluence of art and life. Her friends (whether or not in Fluxus) are frequently invoked throughout Iannone’s work, particularly in A Cookbook, but also in Speaking To Each Other, The Berlin Beauties, and For Emmett, Who Hasn’t Changed A Bit, all of which evince the great importance of Iannone’s friendships and are indicative of other works Iannone made for, with and about her dearest friends.

Nevertheless, I hope the reader finds this selection not only an extraordinary bounty of Iannone’s work but also an invitation into her circle of friends, into an always candid and surprising intimacy with an artist who now as ever is still striving, undaunted.

see also

✼ elsewhere:

Open now — an exhibition of Christian Marclay’s work at Centre Pompidou, designed as a network of affinities and echoes according to the multimedia artist’s way of thinking, combining the preexisting with reinterpretation and metamorphosis.

[...]