Feminist Poetics of the ArchiveA Forum at Tupelo QuarterlyKarla Kelsey, curator

features, 07/01/20

In summer 2020, poet, critic and publisher Karla Kelsey envisioned a forum for Tupelo Quarterly—Feminist Poetics of the Archive—and invited ten participants who “actively engage in the transmission of fragile histories – through creative and scholarly writing, art-making, editing, publishing, translating, curating, teaching” to respond to three of her collective questions/propositions, another question tailored in regard to their own works, and a last posed by a fellow participant. Kelsey writes in her introduction: “Working with these participants on Feminist Poetics of the Archive has been markedly affirming during these dark months of pandemic, police violence, and social unrest. By thoughtfully engaging the past, these responses suggest ways we can empower the future.” It is a generous and thought-provoking repository, well worth a long wander.

The participants are Mary Kim Arnold, Rachel Blau du Plessis, Amy E. Elkins, Camille Guthrie, Ashley Lamb, Poupeh Missaghi, Chet’la Sebree, and Siglio author Danielle Dutton, Siglio editor Lucy Ives and Siglio publisher Lisa Pearson. (Links to each participant’s responses in full.) The forum was originally posted in July 2020 and excerpts from the forum will be included in the upcoming Best of Tupelo Quarterly book.

Below is one question each from Kelsey for Dutton, Ives and Pearson with their answers to get you started.

• • •

karla kelsey

In A Room of One’s Own Virginia Woolf writes of wanting to see how the fictious female writer Mary Carmichael might “set to work to catch those unrecorded gestures, those unsaid or half-said words, which form themselves, no more palpably than the shadows of moths on the ceiling, when women are alone.”

These unrecorded gestures are nothing less than the “strange food” of “knowledge, adventure, art” and Woolf shows us that representations of female engagement with this food are perilously absent in the literature of her time. Not only are these gestures absent but female lives have been so over-written by patriarchal versions of female gesture that they can only by captured by the “talk of something else, looking steadily out of the window.” Each time I re-visit these passages I find them perilously contemporary!

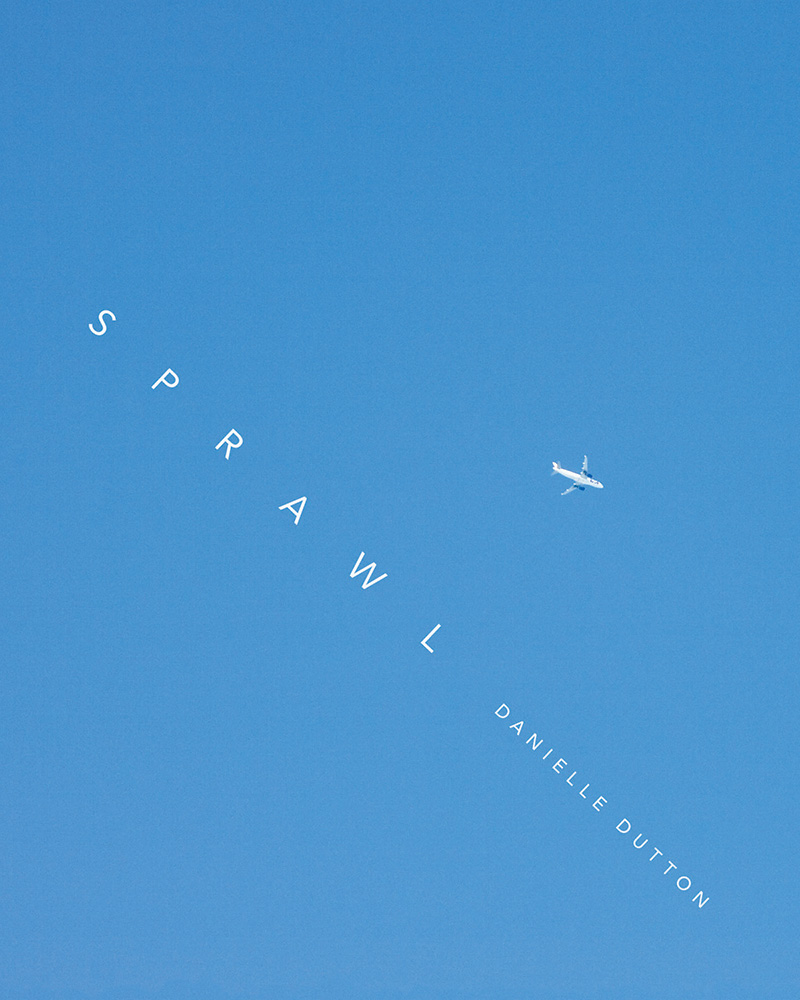

Counteracting this, your books Attempts at a Life, SPRAWL, and Margaret the First share a voracious exploration of such “strange food,” creating windows into the lives of female characters, both historical and imagined, as they hunger and eat. Attempts at a Life operates in short pieces, vignettes that draw on a cast of characters including Jayne Eyre, Alice James, Madame Bovary, and Hester Prynne. SPRAWL is an ekphrastic response to Laura Letinsky’s contemporary domestic still lives and pulses with the rhythm of the body as your narrator circumambulates her suburban neighborhood: “I appear to be free from design or discretion. It is an easy discovery of the ‘feminine.’ I walk through the doorway wearing my aggressively orange hat. I do it over and over.” Margaret the First delivers a complex portrait of celebrity culture through the ambition, sensibility, and brilliance of a 17–century Duchess. What a variety of vital “strange food” you’ve created for readers, and I have yet to mention the lives of books you’ve published since 2009 via Dorothy, a Publishing Project!

My question here for you has to do with technique: Woolf suggests that in order to capture the “strange food” of female life, writers need to “look out the window,” developing alternative techniques to those used in conventional narrative writing. What are your thoughts on this notion? Do you have any favorite techniques?

danielle dutton

For days now I’ve been trying to think of something smart to say in response to this generous question, but the truth is that I operate as a writer and in some ways as an editor very much inside a space of instinct. There’s a kind of silence there. It’s something I’ve spent a decade or so trying to “overcome,” because so many aspects of the job of being a writer and certainly being a teacher of writing demand that we articulate how it is that we do what we do and why. But I write the way I write … because I do. I’m not trying to not write some other way. I’m thinking about how Eileen Myles talks about how most of the interesting work (they’re talking about in poetry) is being done by female writers. They aren’t saying that all work by female writers is better than all work by male writers, but that—okay, I’ll just quote them: “Female reality (and this goes for all the ‘other’ realities as well—queer, black, trans—everyone else) is more interesting because it is wider, more representative of humanity—it’s definitely more stylistically various because of all it has to carry and show. After all, style is practical. You do different things because you are different.” I believe I write toward that “strange food” because I am strange and have always felt strange and estranged, as a girl and a woman, for sure, and also no doubt because of certain inherited mental health struggles, and also because I grew up Jewish in a conservative/Christian small town and (despite the presence in my childhood of plenty of good people) was made to feel like an outsider. All of this is as much a part of my technique as a fiction writer as is the fact that I read Gertrude Stein for pleasure and am not very adept at writing plot. Maybe reading people like Stein and Woolf, maybe just that practice is its own way of looking out the window? Looking differently. Maybe I’m saying that one of my preferred techniques is to look past whatever is at the center, to center myself on the periphery instead.

• • •

karla kelsey

Each of the eleven books that you’ve published is utterly its own, unique entity that observes and reinvents relationship to genre. Each book sits squarely in its room of the archive while at the same time teasing out nuances and transcending boundaries until—voila!—the floorplan has opened. For example Loudermilk, your novel set in an MFA program in Iowa, not only invites us into the trials and tribulations of your young aspiring writer-characters but also includes some of the poems and stretches of prose that they write. When I imagine you at work I imagine you sit before the entire Western (and some of the non-Western) archive of literature. As you write you rearrange the walls and the furniture.

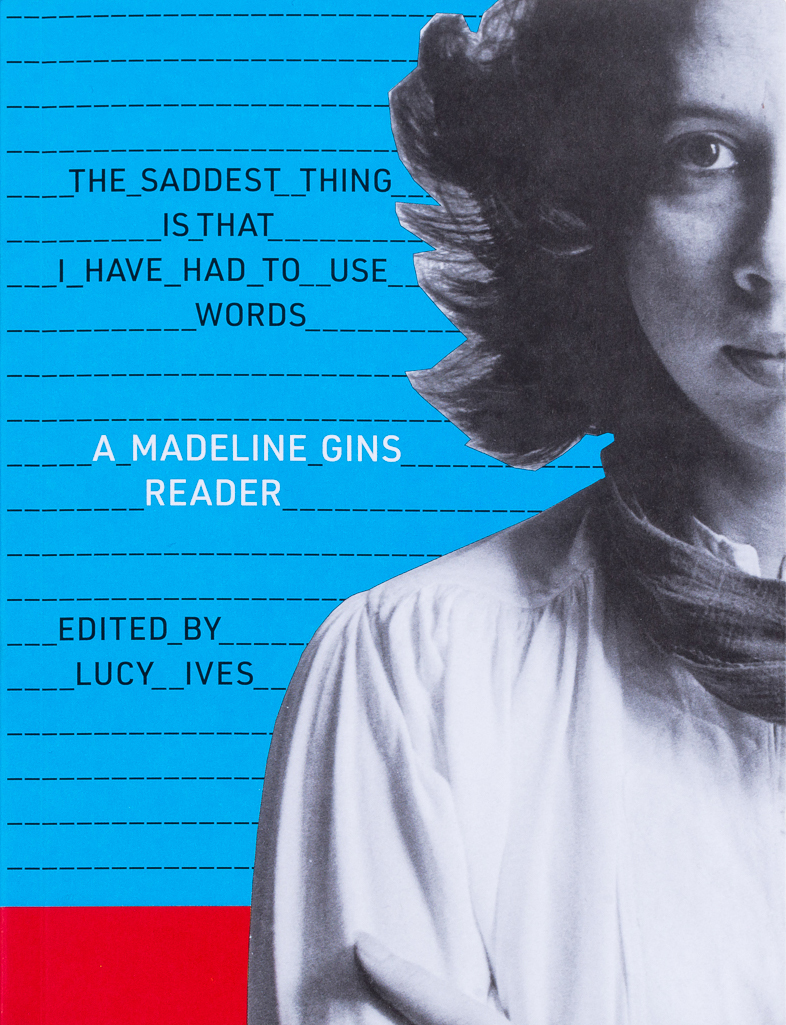

Added to this are your editorial projects, most recently The Saddest Thing Is That I Have Had To Use Words: A Madeline Gins Reader, which collects this extraordinary poet-artist-philosopher’s transdisciplinary writing. You end the book’s introductory essay with the following thought on the undervaluing of poetry, which has stayed with me for months: “Poetry may be writing, of course, but it is not necessarily that; it is also image, performance, gesture, song, social life, gossip, furniture, food, shelter, dance, research, email, garments. This is not to say that poetry has no determined or identifiable form, but that it suffers when it is confined to a stanza. It may well need all the room of a novel, if not the room of an actual room. Madeline Gins is the one who taught me that.”

How has working with Gins’s archive shifted or solidified your sense of genre—shifted and solidified not only what might belong in what genre, but also the usefulness of the concept of genre for the creative practitioner?

lucy ives

Thank you for this question. I wrote in a recent review of a collection of writings by the artist Moyra Davey,

…there is a certain “magic circle” drawn around the authors Davey prefers. “Magic circle” is a phrase that the critic Walter Benjamin applied to the act of creating a collection, and with it he implies at once the synthetic quality of collections and the collector’s selectivity, according these a mildly occult valence via his chosen metaphor. The collector is a creator not just of piles of stuff, but of categories, genres. And with new genres come new aesthetic possibilities.

In my opinion, genre is a way of speaking about conventions of reading and looking, where you sit or stand and whether you’re allowed to talk to other people or move around while you’re communing with an object or text. By combining different or new sorts of things into a given work, the author of that work is suggesting different affects and behaviors to the reader or viewer. Gins, for one, was very good at this sort of thing. I think that this is part of why it’s taken us such a long time to really be able to “read” some of her unpublished work from the late 1960s and 1970s, because the habits and behaviors of mind and body suggested by her writing from this time are really more those of a more densely mediated, projective society (a society like our own), a society to come.

However, as much as I am able to observe what Gins does here, in this writing from her archive, and as much as I’ve learned that this sort of thing is possible (and I marvel at it!), I’m not sure I partake of the same logic in my own work. I am primarily interested in writing speculative texts that are expressly very difficult to write, because of the sorts of mimetic skills they require. I’m interested in teaching myself to imitate different genres of writing—that are not, strictly speaking, important or canonical. For example, for Loudermilk, I taught myself to write a style of poem that would have been written in an academic workshop setting in the U.S. circa 2004. It’s not exactly significant that I was alive at this time and also hanging around these contexts; I didn’t want to write a poem that *I* would have written at this time, in this place. I wanted to write a poem (“the” poem) that would have been written by a young man in his early twenties, in this time and place. So I made some studies and sketches, and I developed a technique to write as this person, writing at this time. It’s a projective exercise. In my novel Impossible Views of the World, I did the same for a minor novelist of the nineteenth century in the U.S., and I also created various other documents written by other people at other historical moments.

As stated, I’m interested in very challenging kinds of writing—kinds of writing that are not precisely personally expressive and which are deeply informed by research, theories of material culture, as well as theories of affect and psychology. I don’t believe that I can or should attempt to counterfeit every kind of writing or every point of view; my choices are specific and have to do with a style of historical learning that interests me at a given point in time. A more recent example of this sort of work is a short story included in my forthcoming collection, Cosmogony, which is written in the style of a Wikipedia entry for the word, “guy.” It’s a strange and synthetic point of view, the “objective” or algorithmic tone of these entries, mixed with the voice of a person who’s struggling to compose this entry, along with themself.

• • •

karla kelsey

In Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of Archives Susan Howe writes: “Often by chance, via out-of-the-way card catalogues, or through previous web surfing, a particular “deep” text or simple object (bobbin, sampler, scrap of lace) reveals itself here at the surface of the visible, by mystic documentary telepathy. Quickly – precariously – coming as it does from an opposite direction.”

With this idea the borders of what we might think archival material contains open to admit deep text and simple object, web-work and library time. Also opened: the process of engaging archival material, allowing us to see the material itself as animated and willful, “revealing itself.” It is as if material has a plan of its own. As such, Howe invites us to overturn a sense of orderly rule, orderly access, of patriarchal law that often dominates historical objects. The call of the archival object invites us to understand the power of texts and objects outside of ourselves to urgently speak.

Have you experienced such a “call” from an archival object or text that led you down the path of response? If so, please describe one such moment and how you responded to the call. Did this response result in a project? Do you now (or did you then) understand this call, or your response to the call, to challenge established systems of value and record? If you never have received such a call what is your process for engaging historical material like?

lisa pearson

Not an object or a text but a name, a spirit: Jean Brown. When I lived in Los Angeles, I was spectacularly dependent on the Getty Research Institute. I won’t spend time here telling you how thrilling it was to ascend the hill (by monorail), walk the marble steps up to the Institute (tucked to the side of the museum), spy hummingbirds among the birds-of-paradise, and catch a glimpse of the ocean if the marine layer had already burned away by mid-morning. My first stop in the circular library—a design that afforded an un-library-like bright Pacific light filtered by long white shades while forcing a disorienting labyrinth of stacks and shelving—was the computer terminal. No matter what I was looking for, no matter what tangent or rabbit hole I was traveling down, however broad or specific my search terms (Dada, Surrealism, Fluxus, concrete poetry, New York School, Language poetry, performance art, conceptual art, mail art, artist’s books, individual artists like Hannah Höch, Dorothy Iannone, Madeline Gins, Alison Knowes, Pati Hill, Mieko Shiomi, Annette Messager, etc. or journals like Heresies or M/E/A/N/I/N/G, or publishing entities like Something Else Press or Hansjörg Mayer), the appearance of “Jean Brown Collection” on the resulting citation seemed both inevitable and fortuitous. It seemed as if everything I was already interested in—and everything my research uncovered that became interesting to me—was part of that collection.

At the time, well over a decade ago, I quizzed the librarians on Jean Brown: Who was this woman, this collector, this consciousness? How did her extraordinary collection (of 6000 books, objects, journals, etc.) come to the Getty? Perhaps I wasn’t asking the right people or the right questions, but no one seemed to have any information other than what is still currently available the Getty’s finding aid. Her current entry in Wikipedia is two sentences, and her 1984 New York Times obituary (online since 2014) is less than 350 words.

Without knowing anything about her, I nonetheless felt her very particular presence. The name “Jean Brown” itself was, for me, the conduit of Howe’s “mystic, documentary telepathy.” When her name appeared on a citation, I sensed that this object or book had been carefully selected, cared for, considered, held. That it was a source of experience, of pleasures. As the citations accumulated, I also sensed a remarkable generosity of spirit: even as some corners of her collection were well-demarcated in art history (the Dada and Surrealist books, mostly, which were in themselves still an exquisite set—see below), it was clear that the very individual hand and eye highly valued what had been marginalized, obscured, dismissed, or just outright ignored. This was not a collection that was meant to be conclusive, nor did it have the kind of swagger of expertise (though clearly multiple bodies of knowledge informed it—as well as instinct); rather the connections between these books and objects were electrified by her consciousness, her curiosity, her ability to see across and between and beyond. In Jean Brown, I felt a great kinship for the expansiveness that I aspire to as a publisher. I knew all this by just spending time in what was once her library, her collection of things. When her name appeared on a citation, I felt awash in some combination of exultation, intimacy, communion, trust, confidence. There was a transmission. When her name was not there (which was infrequent), I might have felt a twinge of loneliness, and then summoned the courage to further complicate and add to the matrix of connections: an ever-expanding universe.

In 2008, Siglio published The Nancy Book by Joe Brainard (the first book, fueled by much serendipity, good will, and a great deal of love for Joe and his work). I got a call from a woman in New York who wanted to see the accompanying limited edition. She was visiting her daughter in LA—could she come by? At that point, I don’t think anyone but friends had visited my garage-office so I remember being a bit nervous about the presentation. But it was an easy conversation; she loved the edition, and we talked for quite awhile about mutual interests. I chalked our connection up to the camaraderie of loving Joe’s work. As she was leaving, she stopped, surveyed the garage (and me, I think), and said how much Jean Brown, her partner’s mother, would’ve loved the edition, loved The Nancy Book, loved Siglio. My reaction was to suddenly embrace Susan who had likely embraced Jean. Instead of books, bodies. Another, equally visceral transmission.

I learned from Susan that Jean Brown was a librarian in Springfield, Massachusetts, who had sold her entire collection to the Getty when (according to hearsay) they only wanted the Dada and Surrealist publications. (Fortunately, later GRI curators, like Nancy Perloff, recognized what an extraordinary trove the Jean Brown Collection actually is, particularly the Fluxus objects and concrete poetry works.) She was friends with some of the greats of the 20th century avant-garde—Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, George Macunias—but she was also deeply invested in all corners of experimental work and often commissioned and bought work to support artists who weren’t selling anything at the time, even though she was by no means wealthy. In February 2019 a short film “Not Jean Brown” played for a single night at the Emily Harvey in NYC (and I was not in the city to see it, alas). The filmmakers wrote a lovely homage to Jean Brown which you can find on their website. She seems to be exactly whom I imagined her to be, and likely more. She remains a presiding spirit over Siglio.

• • •

n.b. In 2021, the exhibition Fluxus Means Change: Jean Brown’s Avant-Garde Archive took place at the Getty Research Institute accompanied by the eponymous book, and there’s a long, chatty article preceding it at Artsy. Teaser image: detail from Umberto Romano, Portrait of Jean Brown, 1938.

see also

✼ @sigliopress:

Yes, for the foreseeable future, any ongoing catastrophe metaphor applies: tsunami, fire, mudslide, earthquake, aftershock. Indie publishing is never for the faint-hearted. Now, it requires superpowers. Meanwhile, I have a drugstore umbrella, knee-high wellies and a spade.

[...]