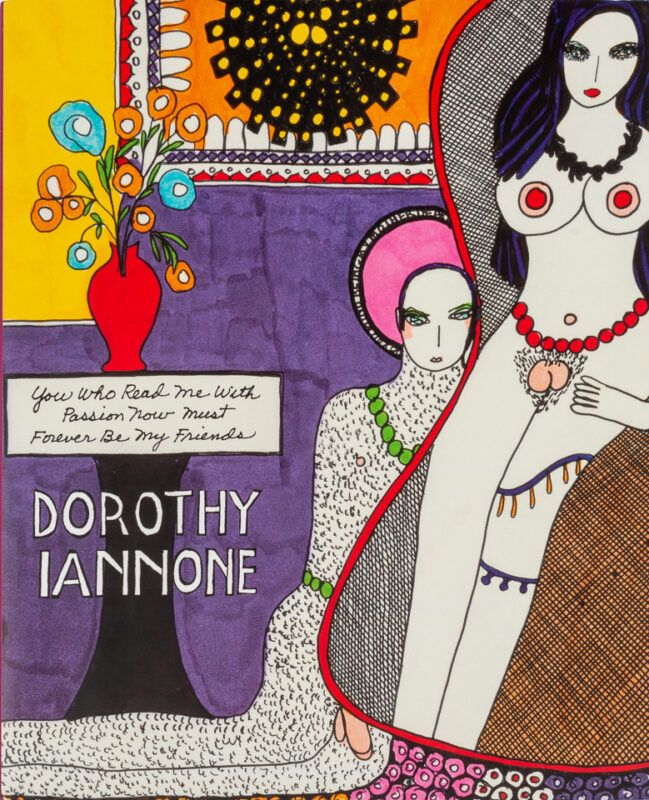

She Is DangerousDorothy Iannone, 1933-2022

affinities, 01/04/23

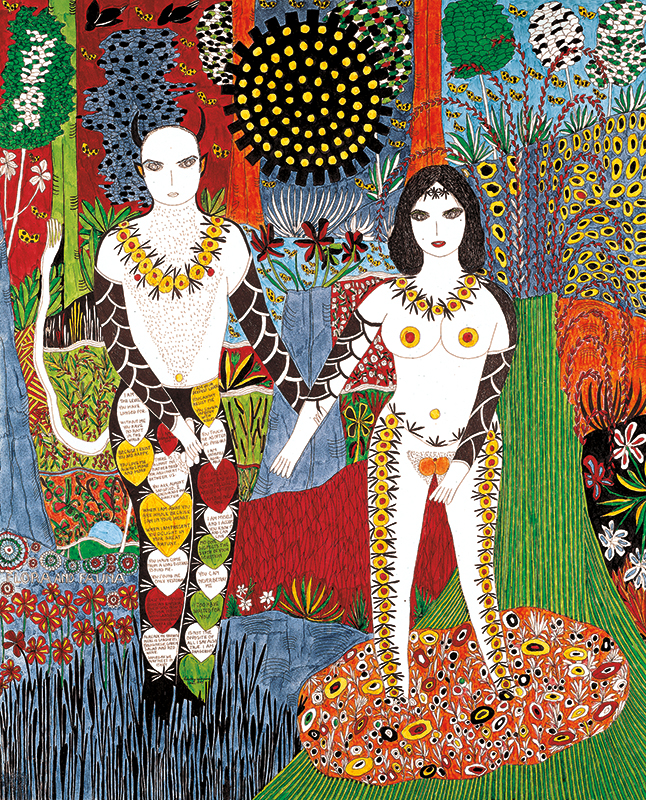

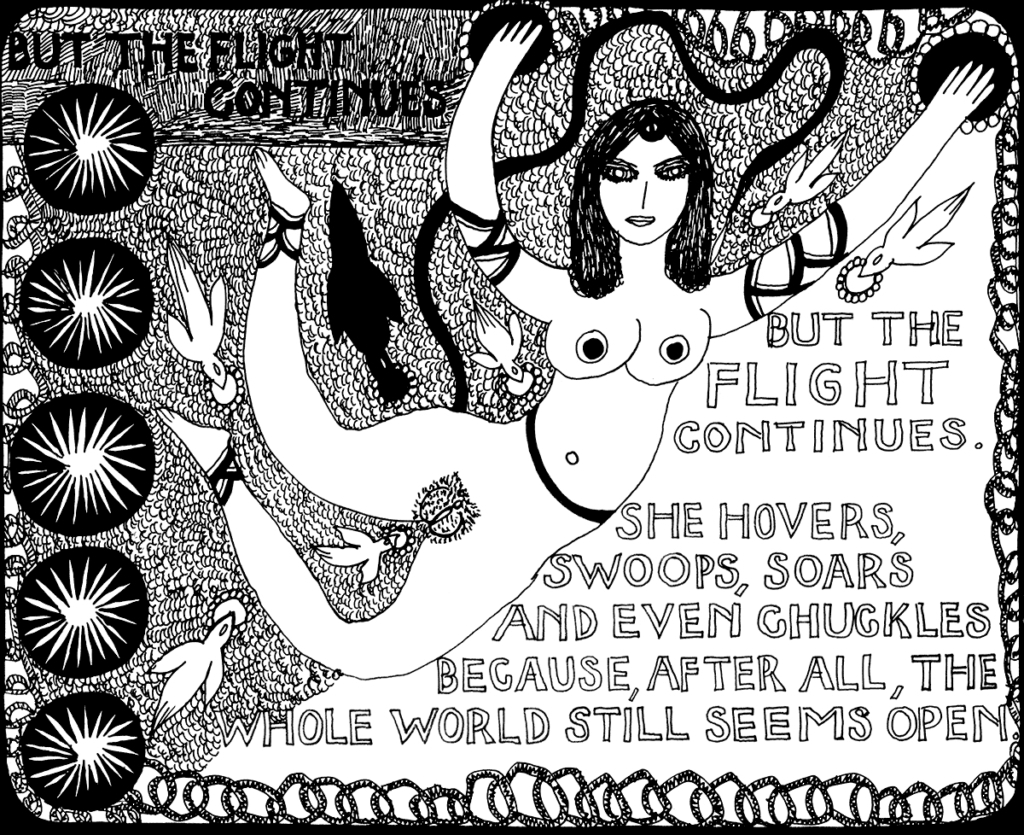

“Flora and Fauna,” 1973. From You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy Iannone, Siglio, 2014.

On December 26, 2022, Dorothy Iannone passed away in Berlin, her home since 1976. She was a self-taught artist who made exuberantly sexual, joyfully transgressive, and often autobiographical image+text works, radical in their inversion of binaries, and often tender in the incorporation of her lovers and friends. She worked tirelessly, in obscurity, for decades—relegated to side-note status in discussions of Dieter Roth, Emmett Williams, Robert Filliou, etc. Then, in the last fifteen years of her life, she achieved the recognition and admiration that had long eluded her. Or, perhaps better said: what she achieved in her life was finally recognized.

The obituaries this past week quote Filliou (a true and lovely assessment—from 1975), invoke Roth (one in the first paragraph, the others thankfully further in), and use these words or some version of them: “sex,” “censorship,” “liberation,” “love.” Those words certainly apply, as do “spirituality” and Dorothy’s phrase “ecstatic unity.”

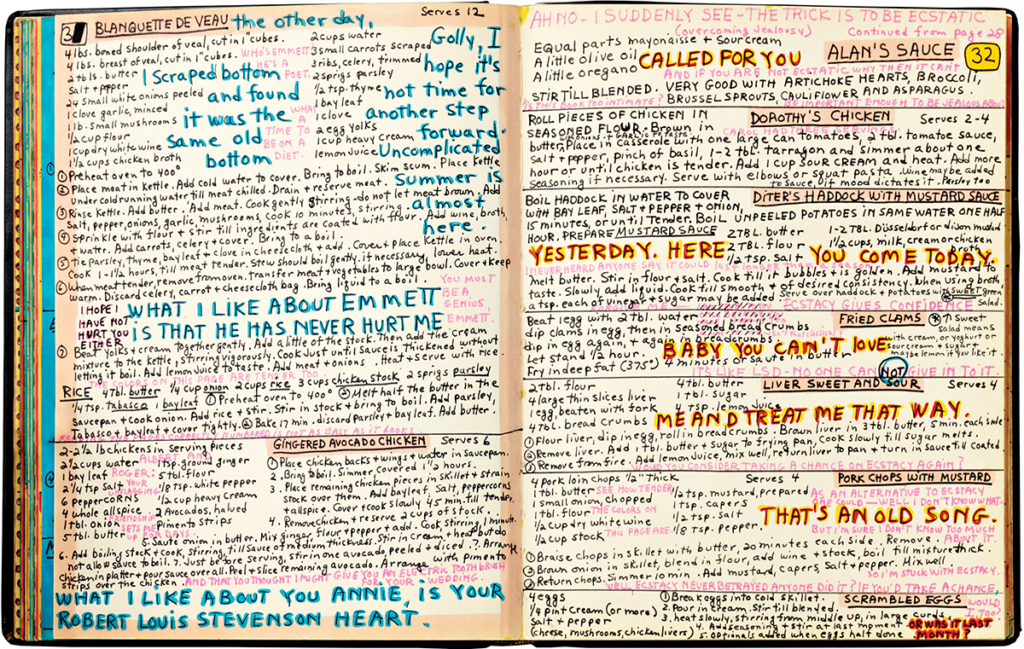

What is absent—and how would the writers of these obituaries know?—is the recognition that her work is words. Yes, those words particularly, how she experienced, understood, defined and redefined them (literally, figuratively, textually, visually), but also how the reader, whom she often lovingly invokes and directly addresses, ingests her words, served up in the most delicious and inviting ways. Other words: “search,” sometimes “flight.” Out of those words, Dorothy was always in the process of making/remaking a new world, her world, perhaps unfinished, imperfect, always rich with intended (and unintended) contradictions and provocations.

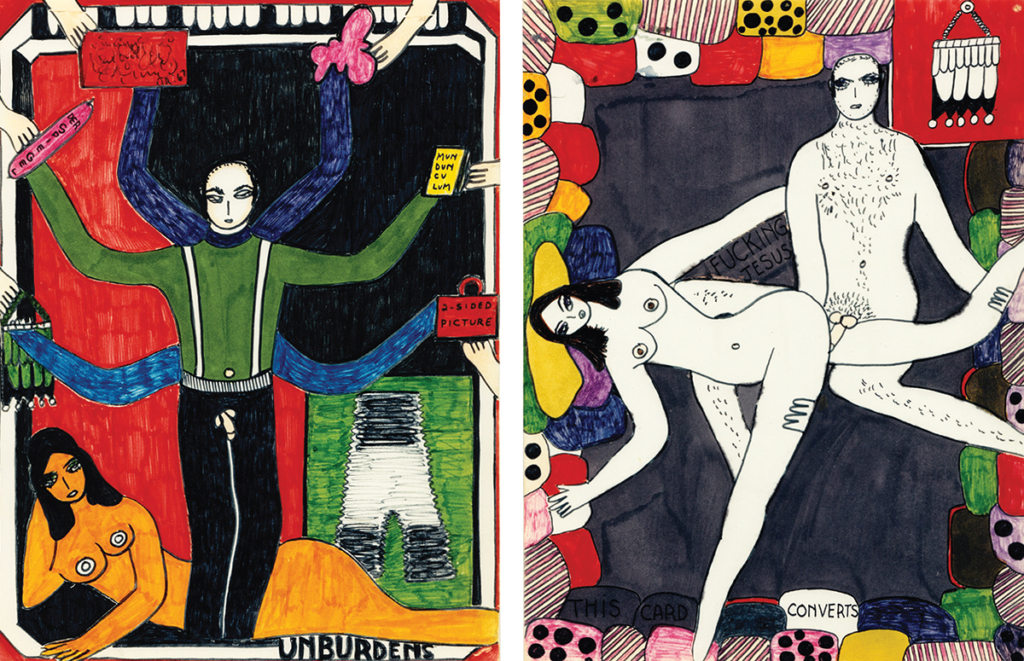

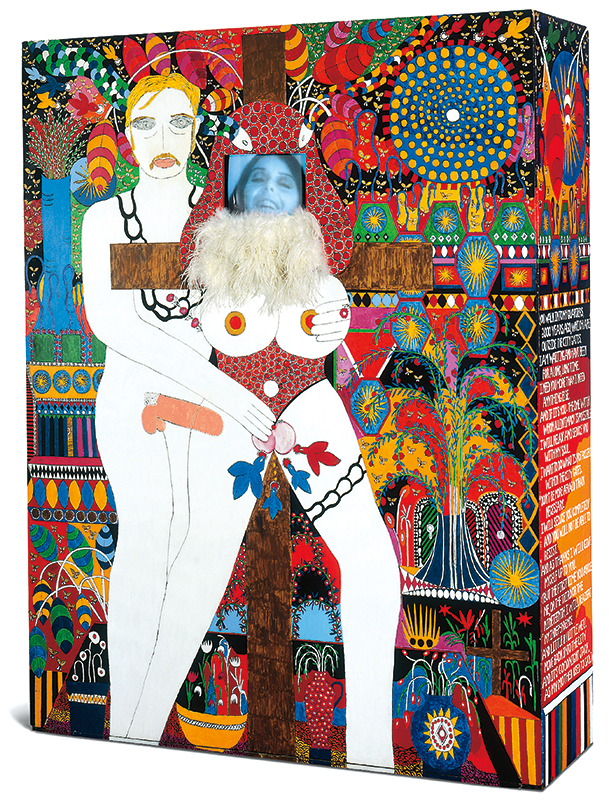

Detail from “L’Adorable Trixie,” 1975-1978, by Dorothy Iannone. From You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy Iannone, Siglio, 2014.

What is also not quite said—perhaps because it seems commonplace for so many women artist/writers?—is that beyond the outright acts of censorship (and the actual destruction) of her work, there was also an almost-fifty-year-long dismissal of her work, which she acutely felt. Despite being ignored, even “mildly ridiculed,” as she said in an interview, she kept making work, whether or not it would be seen or read, censored or destroyed.

Finally, in 2005, at the age of 72, Dorothy was invited to recreate “I Was Thinking of You” (see below!) for the Wrong Gallery at the Tate Modern. It was subsequently remounted at the Whitney Biennial in 2006, the same year Kunsthalle Wien mounted “Seek the Extremes,” an exhibition focused on works by Dorothy and Lee Lozano (an inspired pairing of two neglected artists for which the catalog is far too thin—please, will someone write about these two artists in relationship to second wave feminism?!). In 2009, Lioness, her first solo exhibition in the U.S., took place at the New Museum. Yet, there was still no book dedicated solely to her work.

At that time, the only existing, available trade publications were two volumes of correspondence between her and her lover Dieter Roth. (The first, Dieter and Dorothy, published lovingly by bilgerverlag Zürich in 2001, was the most exquisite and may have been my first encounter with her work.) There were also long out-of-print artist’s books, mostly published by Hansjörg Mayer in tiny editions, so scarce that Printed Matter (so I was told) never had her masterwork artist’s book Danger in Düsseldorf in its inventory. It was only in the context of her relationship with Roth that one might be able to locate Dorothy’s own writings, drawings, voice, vision: she was invisible without the man whom she called her muse. This oversight seemed, to me, almost criminal.

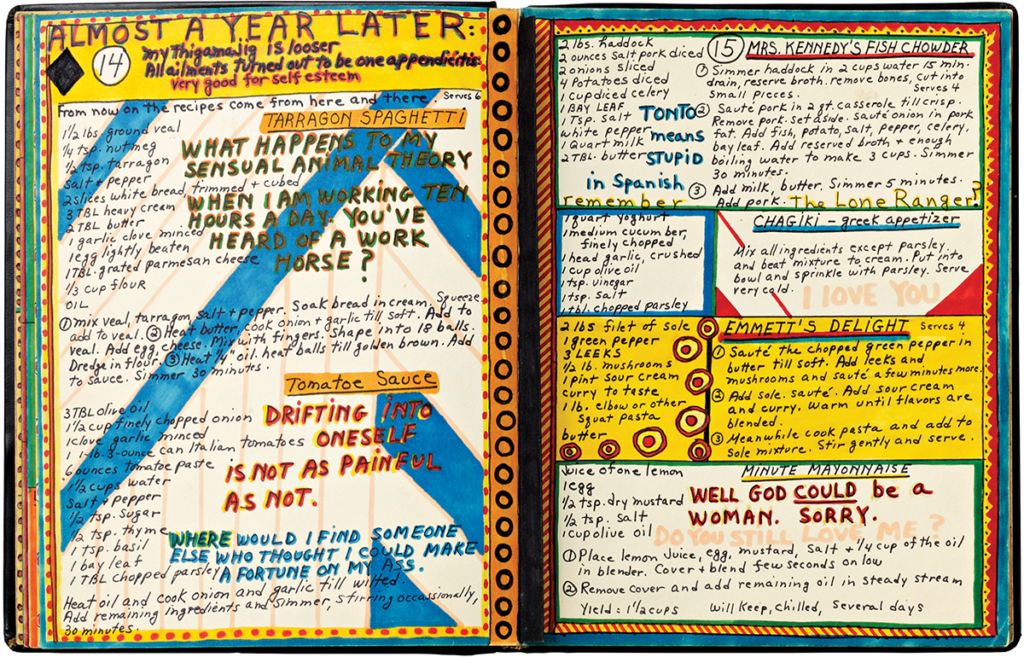

Detail from A Cookbook, 1969. From You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy Iannone, Siglio, 2014.

I loved Dorothy’s work—what I knew of it, at least. I had a desire to find it, see it, read it closely, completely, as much of it as I could locate, but all of it—if not out-of-print—was unpublished, unreproduced, thus unfindable. The compendium of her work I edited, You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends (2014), was fueled by the resulting outrage. A few years earlier, about the time I published It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers in 2011 (another attempt to rectify some wrongs)—which included Dorothy’s witty summation of a girlhood marked by joyous and committed resistance—I met up with the writer Trinie Dalton (I remember clearly, at the Casbah Café in Silver Lake) where we discovered our mutual passion for her work and our fury that it was so unavailable.

Much of what excites us about Dorothy’s work is articulated in the book, hatched that very day. Trinie wrote an extended and deeply considered essay for You Who Me Read With Passion… (there’s an excerpt here), and in my foreword, I profess my love for Dorothy’s work, a love that is simply evinced by the book itself, which took almost three years to take shape, with the ambition to make enough room for Dorothy to fully speak. There’s a possible novella about this process—a real lesson in the many aspects of editing—but I’ll share just one fond memory.

In October 2012, I visited Dorothy in Berlin to spend several days with her talking, looking, reading as we finally started the book in earnest. At the end of the first day, she directed me to an oversized wicker chair (just like the one on the cover of You Who Read Me…), made me a cup of tea, served it in a bone china teacup with saucer, each adorned with a circle of plump, smiling Buddha faces (if I remember correctly). Then she turned on the TV and plunked a VHS tape in to the player. “These are the outtakes from ‘I Was Thinking of You,'” she told me.

In black and white, Dorothy’s gorgeous face filled the frame, looking straight at the camera. She closes her eyes. Then she sighs, purrs, coos, moans, while her face slowly drifts down to the bottom of the frame—leaving a mostly blank space with just the top of her head—as she climaxes. I watched the first few versions, each about five minutes give or take. I was riveted (even, admittedly, a little startled, if only because it came to mind that my mother was only a few years younger than Dorothy). Meanwhile, Dorothy watched me, quite tickled, and we laughed as she explained how challenging it was to stay in the frame while masturbating. Then we continued talking while the video rolled on, our conversation punctuated by sounds of her pleasure. It was all very much Dorothy, in so many ways.

At the end of her life, as she was able to bathe in adoration and opportunity (even recently designing a handbag for Dior), it is easy to forget that she worked for decades without it. It is easy to forget her stamina, her fight, her persistence. Her bold, declarative female figures are now recognizable—inimitably Dorothy—with ripe breasts and vulvas that are almost testicular in their roundness. Sometimes the women stand alone. Most often they stand with men, holding their hands, lying in bed, maybe arguing about who will turn out the lights. The women are sometimes on their knees, but the men are too, all depicted in mutual states of pleasure, giving and receiving. The surface, though, does not tell the entire story. In Dorothy’s work, not all is what it seems. It is also more than one thing at once. She writes, “Is not the opposite of all I say also true. I am dangerous.” Her great gift is this invitation to read—dangerously. And to be her friend while we’re at it.

Adieu, Dorothy. With love, Lisa.

“I Was Thinking of You,” Dorothy Iannone, 1975. Courtesy of the Ahlers Collection. From You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends by Dorothy Iannone, Siglio, 2014.

see also

✼ ex libris:

What’s going to happen in the next four years? A 1600+ page cautionary tale… Clearly, not enough people are reading anymore.

[...]