Two Halves: Unica ZürnA short, constellated biography

affinities, 11/12/11

Selected, edited and arranged by Jasmine Francis.

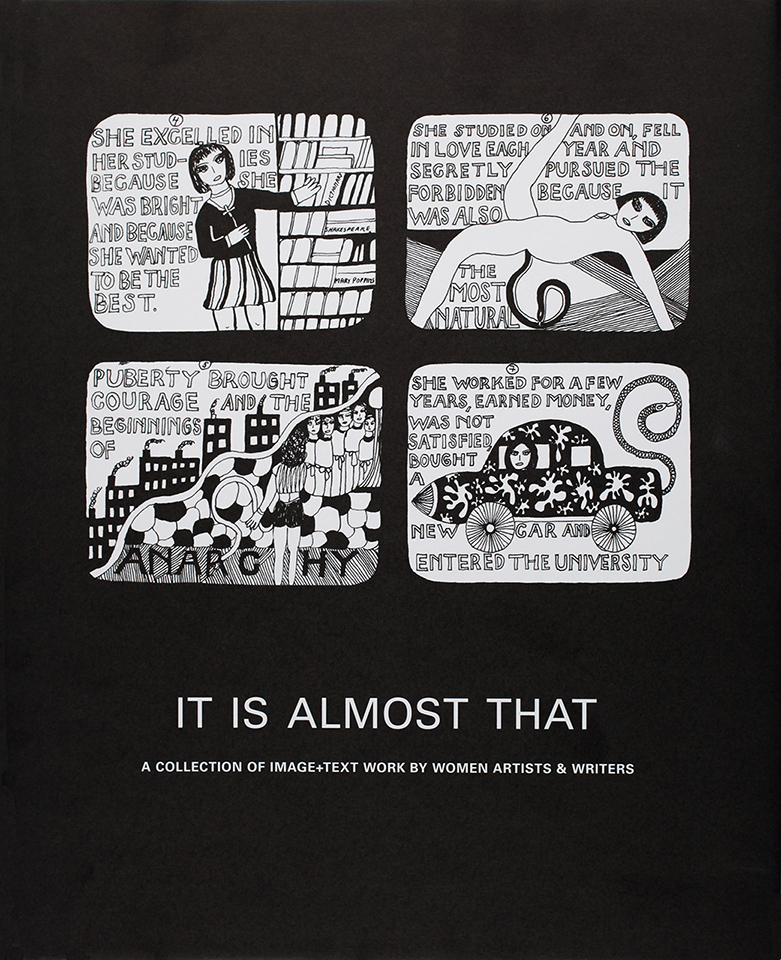

Excerpts of drawings and texts from Unica Zürn’s The House of Illnesses was included in Siglio’s 2011 publication It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers. One of my aims in editing and publishing the book was to bring attention to artists and writers who have been overlooked or too tightly categorized and thus are known to a only a very particular audience. Zürn is certainly case in point. While the inclusion of her work in It Is Almost That may help to remedy that, this blog post—authored and organized by Siglio intern Jasmine Francis—pulls together disparate sources of information to serve as a kind of hub and as resource for readers looking for ways to navigate (sometimes sparse) material on artists and writers who are not (or not yet) as well-known as we think they should be. See our other post on Charlotte Salomon and my short biography of Dorothy Iannone published in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, 2014. —LP

From my earliest childhood, the first woman’s eyes I encountered conveyed the same uncontrollable anguish spiders cause me … This is why I very soon divided myself into two halves.1

—Unica Zürn

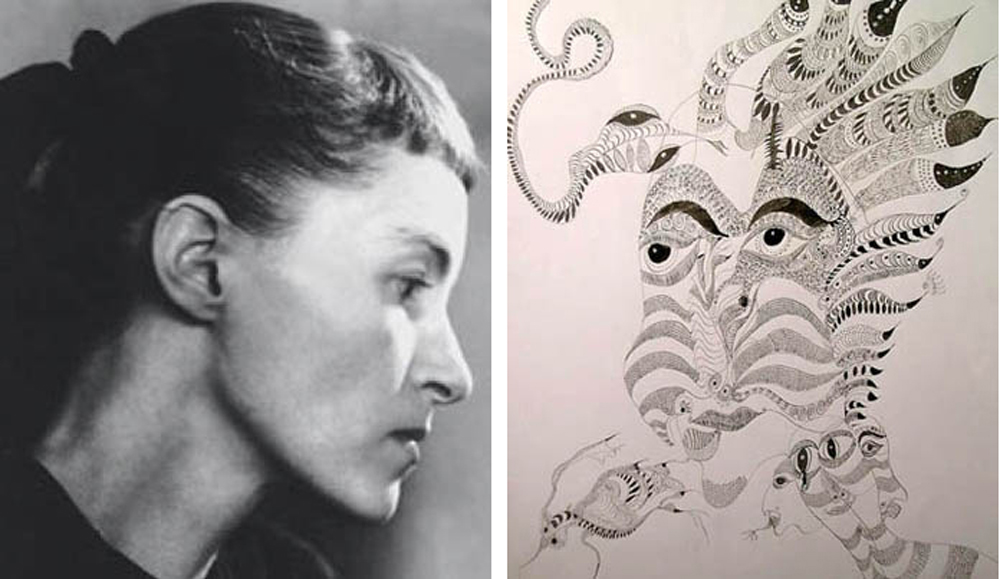

Left: Photo of Zürn; Right: Drawing by Zürn, 1961.

1.

A LITTLE ABOUT UNICA ZÜRN

Unica Zürn was born in 1916 in Berlin-Grunewald as Nora Berta Unica Ruth. Her mother was Helene Pauline Heerdt, and her father was Ralph Zürn, a writer and editor and cavalry officer who was stationed in Africa; he often brought Zürn exotic, ephemeral gifts he had collected in his travels. Her parents divorced in 1930. During her childhood, Zürn often dreamed of a male fantasy figure she dubbed “the man of Jasmine.” She left school at the age of fifteen, and in 1933, after a stint at business school, she worked at the studios of Universum Film AG in Berline as a shorthand typist. From 1936 to 1942, she wrote for commercials.

In 1942, Zürn married Erich Laupenmühlen and had two children with him, Katrin (born in 1943), and Christian (born in 1945). After divorcing her husband and losing custody of her children, she developed a relationship with the painter Alexander Camaro, who introduced her to painting. Around this time (1949–1955), she wrote short stories, reports for journals in Berlin, serials for newspapers, radio plays, and skits for a cabaret called “The Bathtub.” She separated from Camaro in 1953, the same year that she met Hans Bellmer in Berlin during an exhibition at the Galerie Springer.

Bellmer, a German Surrealist, encouraged her to pursue “automatic” drawings and to work on her anagrams (poems resulting from the rearrangement of the letters of a word or phrase in order to produce a new word or phrase, using all the original letters only once). Zürn also experimented with oil painting, but quickly abandoned the pursuit. Her drawings and anagrams were presented under the title Hexentexte by the Springer Berlin Gallery in 1953. In the same year, she had her first solo exhibition of automatic drawings in the Galerie Le Soleil dans la Tete in Paris (where she also had another exhibition in 1956). In attendance were well-known artists, writers and philosophers such as Breton, Man Ray, Hans Arp, Joyce Mansour, Victor Brauner, and Gaston Bachelard.

I was allowed to accompany Bellmer during all the portrait sittings: Man Ray, Gaston Bachelard, Henri Michaux, Matta, Wilfredo Lam, Hans Arp, Victor Brauner, Max Ernst … There are those who must be adored and others who adore. I have always belonged among the latter. Being full, constantly full of wonder, admiration and adoration. Remaining in the background, watching, looking—that is the passive manner in which I lead my life.2

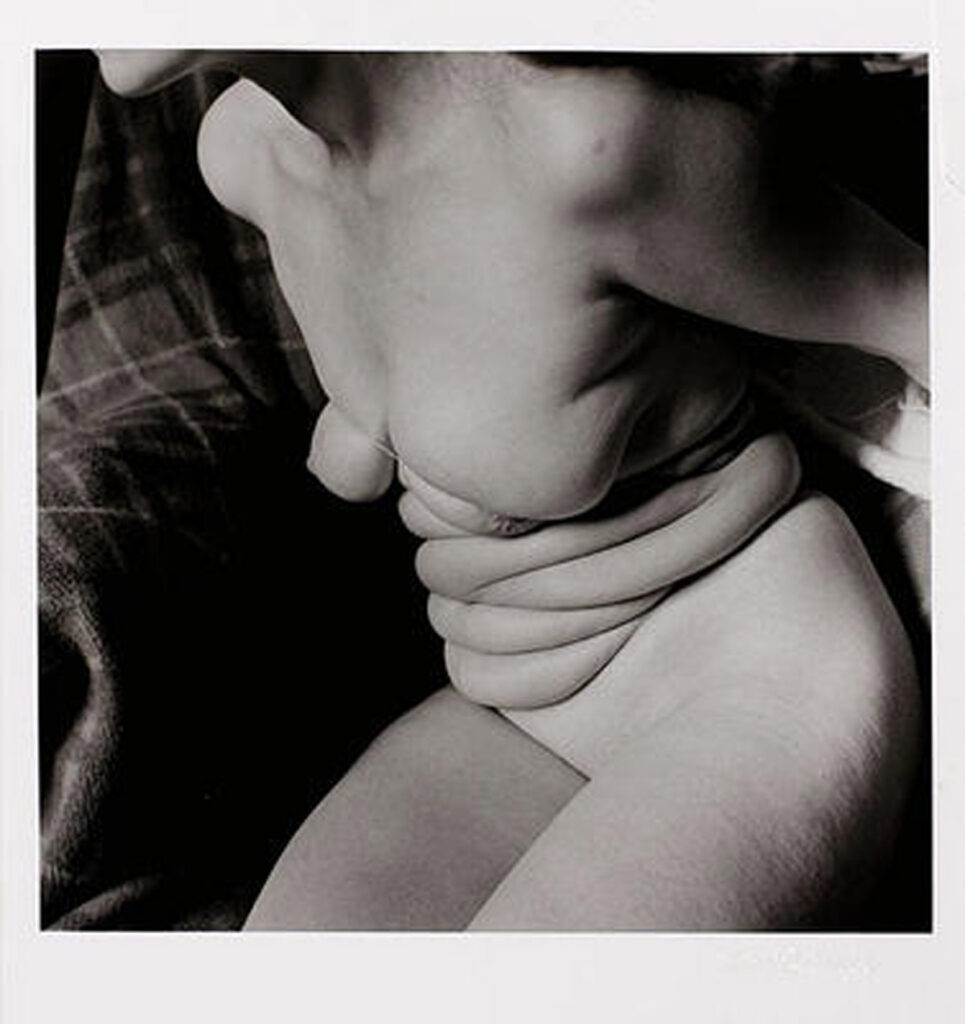

In 1954, Zürn moved to Paris with Bellmer and met Man Ray, André Pieyre de Mandiargues, and Max Ernst. In 1958, she participated in a series of photographs with Bellmer, who tied her up with ropes so tight that they cut into her naked body. The photos were called “Unica Tied Up,” and Bellmer’s 1959 exhibit Doll (La Poupee) that included these photos were a success. In 1959, Zürn’s own work was included in the large surrealist exhibition at the Galerie Cordey in Paris.

In 1957, Zürn met Henri Michaux, identifying him with “the man of Jasmine” from her dreams and took the drug mescaline with him. Zürn’s mental health began to deteriorate that same year. After stays at multiple clinics prompted by a nervous breakdown and schizoprenic crisis, the administration of psychoneural drugs, and two suicide attempts, she returned home in a wheelchair, where she destroyed many of her works. Later that year, she was then taken to the Sainte-Anne clinic in La Rochelle (and remained there for three years). Henri Michaux brought her drawing materials so she could continue to work. After this, she was interned in various other psychiatric clinics, including “La Fond” in La Rochelle (1966) and Maison Blance at Neuilly-sur-Marne (1969 and 1970). One of her doctors was Gaston Ferdiere, who was considered a friend of the surrealists.

Her illness provided inspiration for much of her writing, including The Man of Jasmine, which was written between 1963 and 1965 and a sketchbook of drawings, created from 1963-1964, entitled “Oracles and Spectacles” (one of her unpublished works). She published Dark Spring in 1969, while The Man of Jasmine was published posthumously in 1971. An expanded section from The Man of Jasmine, entitled The House of Illnesses, was published in 1986.

On April 7, 1970, Bellmer, now paralyzed from a stroke in 1969, informed Zurn that he could no longer be responsible for her. On October 18, 1970, she was discharged from La Chesnaie de Chailles, an asylum. The following day, she committed suicide by jumping from a sixth-story window in the apartment she shared with Bellmer. Bellmer, who died in 1975, was buried next to Zürn at his request at the Père-Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. Their grave is marked with the words Bellmer had written for Zürn’s funeral wreath, five years prior: “My love will follow you into Eternity.”3

Sources

- Unica Zürn, Gesamtausgabe (Berlin: Brinkmann and Bose, 1988). Cited in: Unica Zurn: Dark Spring, curated by João Ribas, edited by Jonathan T.D. Neil and Joanna Berman Ahlberg, Drawing Papers 86 (New York, NY: The Drawing Center, 2009).

- Unica Zürn, Notes of an Anaemic, 1957, published in Das WeiBe mit dem roten Punkt (Berlin, 1981). Cited in: Introduction to The Man of Jasmine by Malcolm Greene (London: Atlas Press, 1994).

- This biography assembled from the following sources: Ubu Gallery, Wikipedia “Unica Zürn,” Wikipedia France “Unica Zürn,” Art Brut, Atlas Press, and the essays by João Ribas and Mary Ann Caws in “Unica Zürn Dark Spring” (from The Drawing Center catalogue).

2.

ZÜRN, THE ARTIST

In a letter to Gaston Ferdiere, the doctor who Zürn shared with Hans Bellmer (and Antonin Artaud), Bellmer writes:

During a relaxed after-dinner conversation at my mother’s house, Unica was doodling distractedly (the way one does while on the telephone). With my clearly experienced eye I immediately recognized her remarkable gift for automatic drawing. I pointed it out to her: after two or three days, she was making, with intense delight, drawings of which each one was of good quality.1

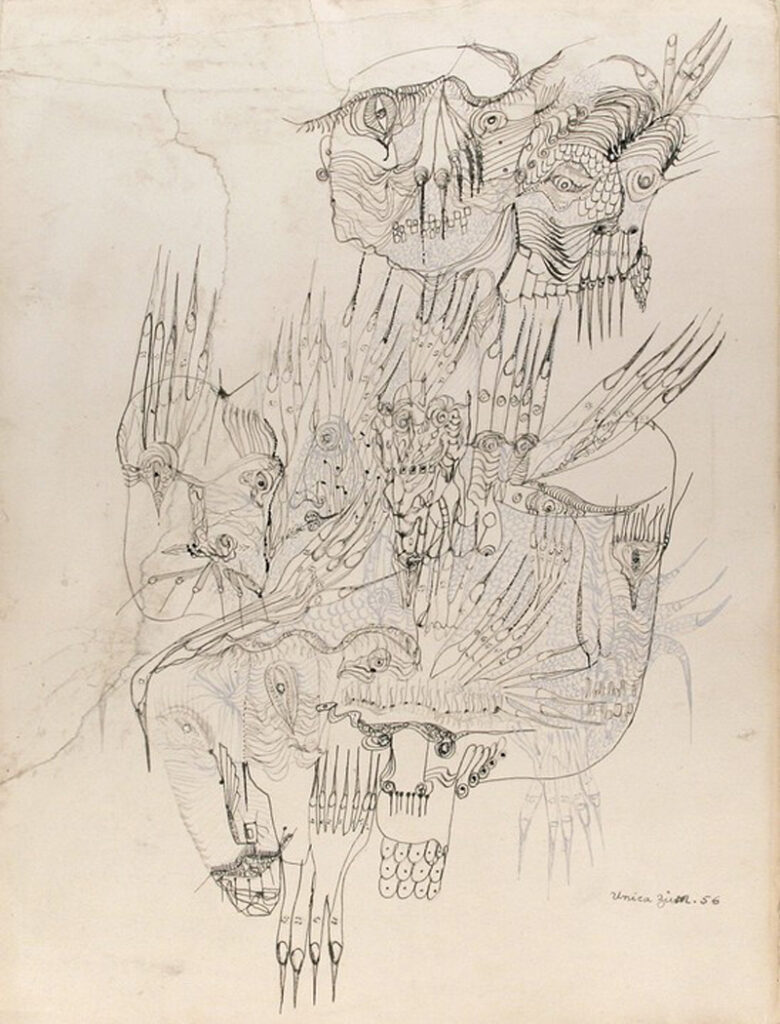

1954.

More of Zürn’s early work can be found here.

On May, 1956, Zürn has her first solo exhibition in Paris at the Gallery “Le Soleil dans la Tête.” She sold four paintings:

So my show is over […] The drawings were sold, like something like this: the first was like a rabbit, with breasts on the chest, with bones and a ghost in the stomach (ink China black). The second was, as said Hans, a sort of “buffalo-bug” […] The third was a “sole traveler” attached to a repulsive octopus […] The fourth was […] kind of a big bell, from which emerged other insects.2

1956.

1956.

Zürn writes in an excerpt from her novel The Man of Jasmine:

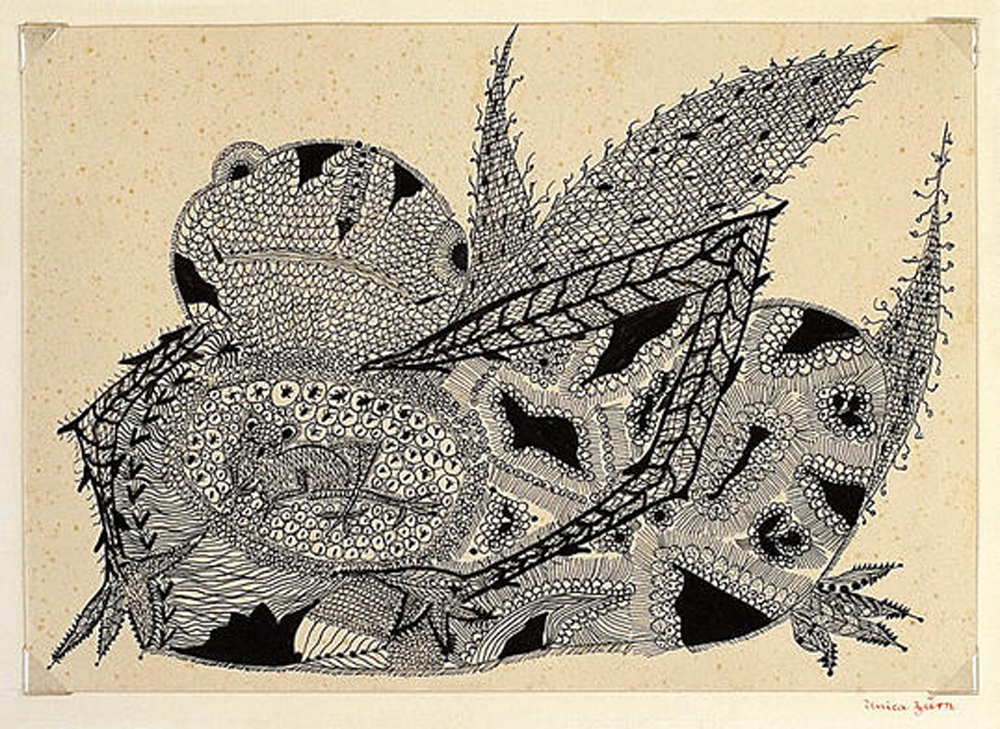

One day at Wittenau the head doctor had called her to a room in which a group of students and psychologists from other clinics was assembled, and asked her to comment on her drawings as he showed them to the others. The drawing Recontre avec Monsieur M (ma morte) prompted a discussion, and she was asked: ‘Why did you cover the entire surface of the paper right to the edges? On the others you’ve left the space around the motif white. And she had answered: “Simply because I couldn’t stop working on this drawing, or didn’t want to, for I experienced endless pleasure while working on it. I wanted the drawing to continue beyond the edge of the paper – on to infinity…” 3

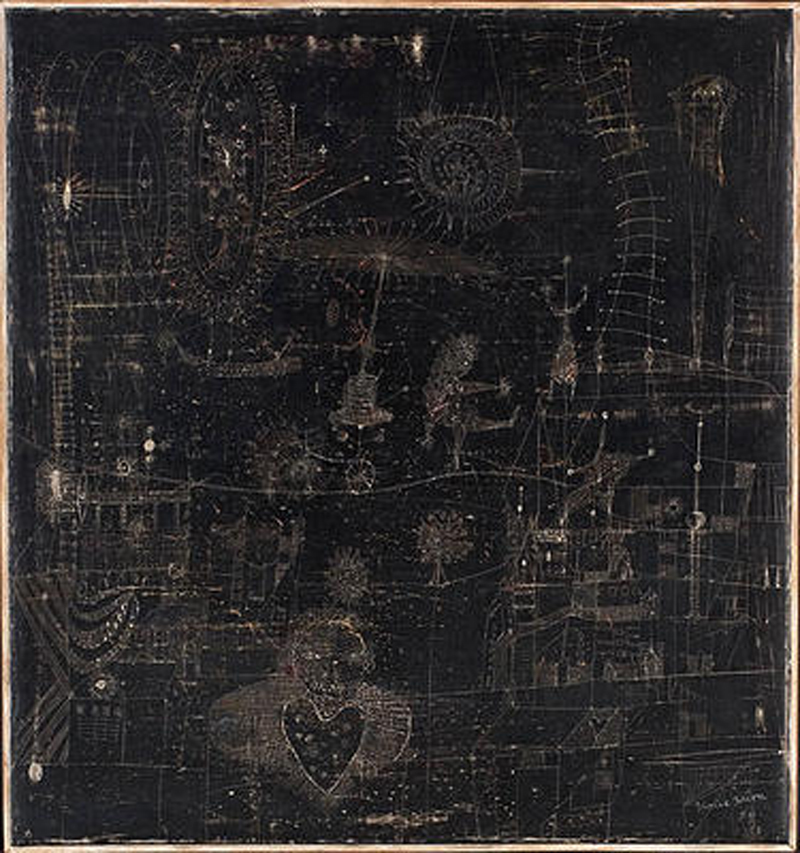

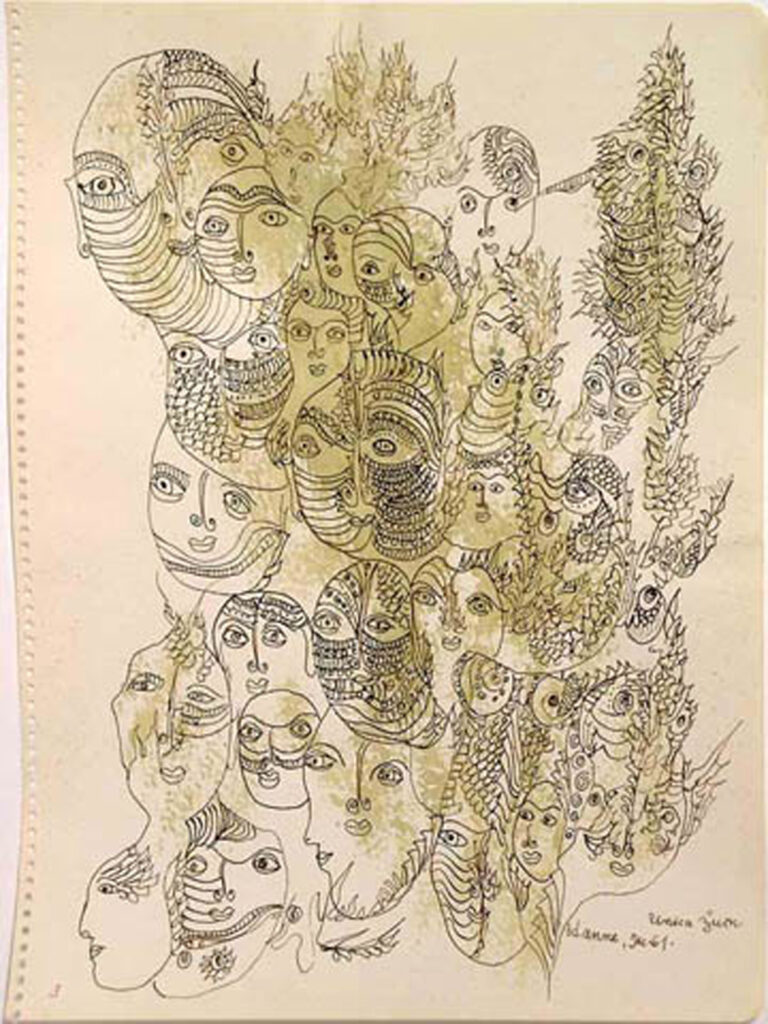

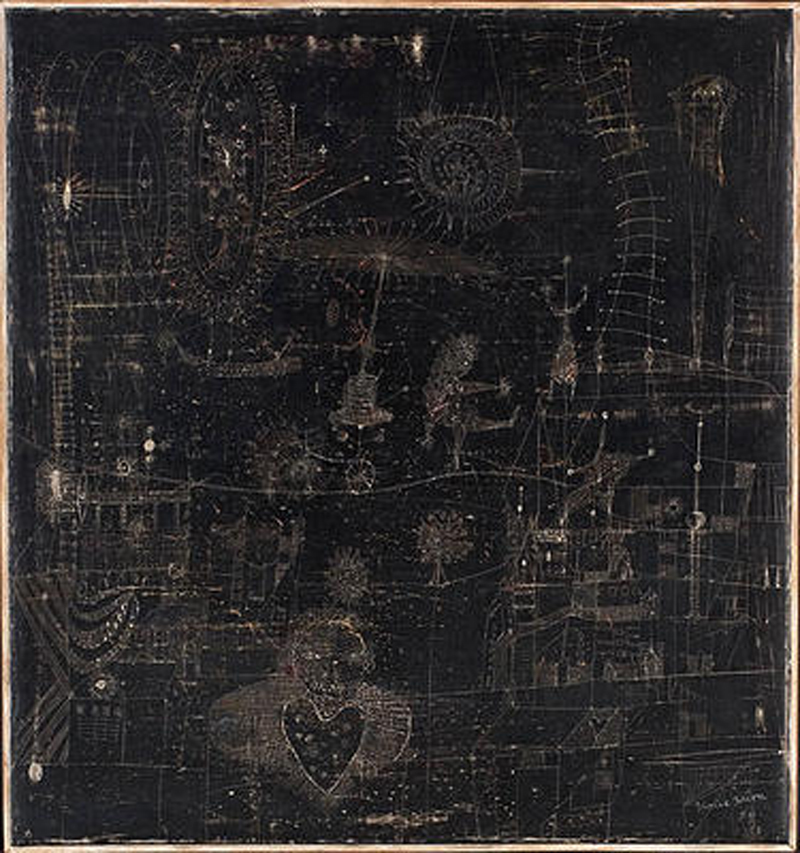

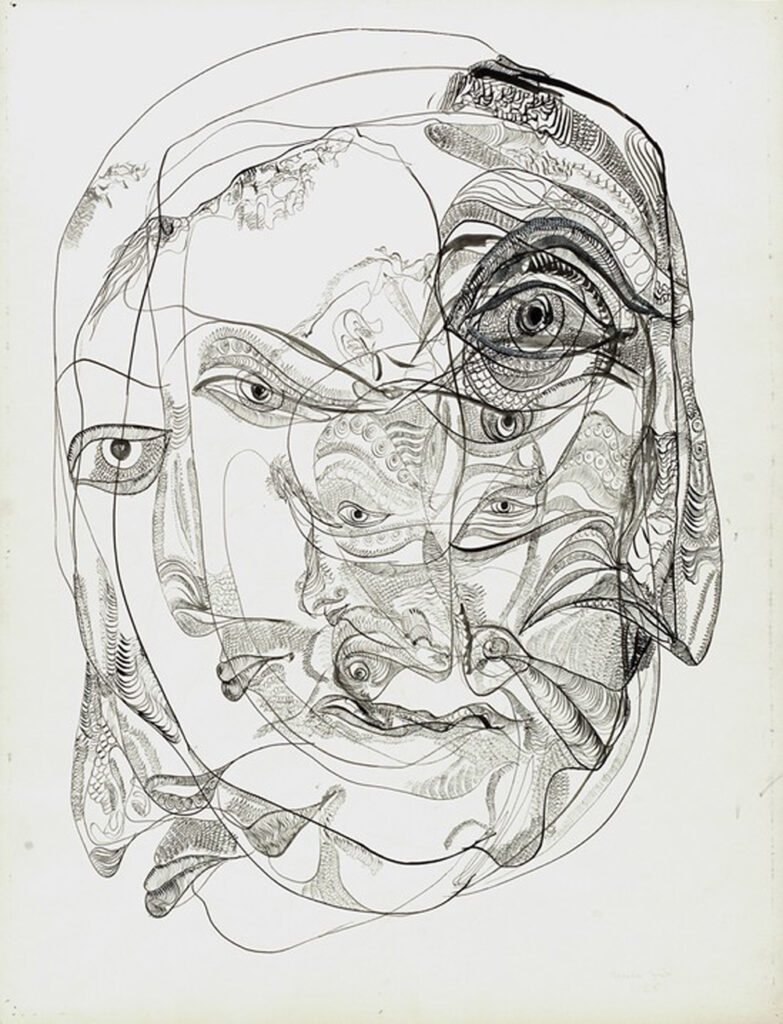

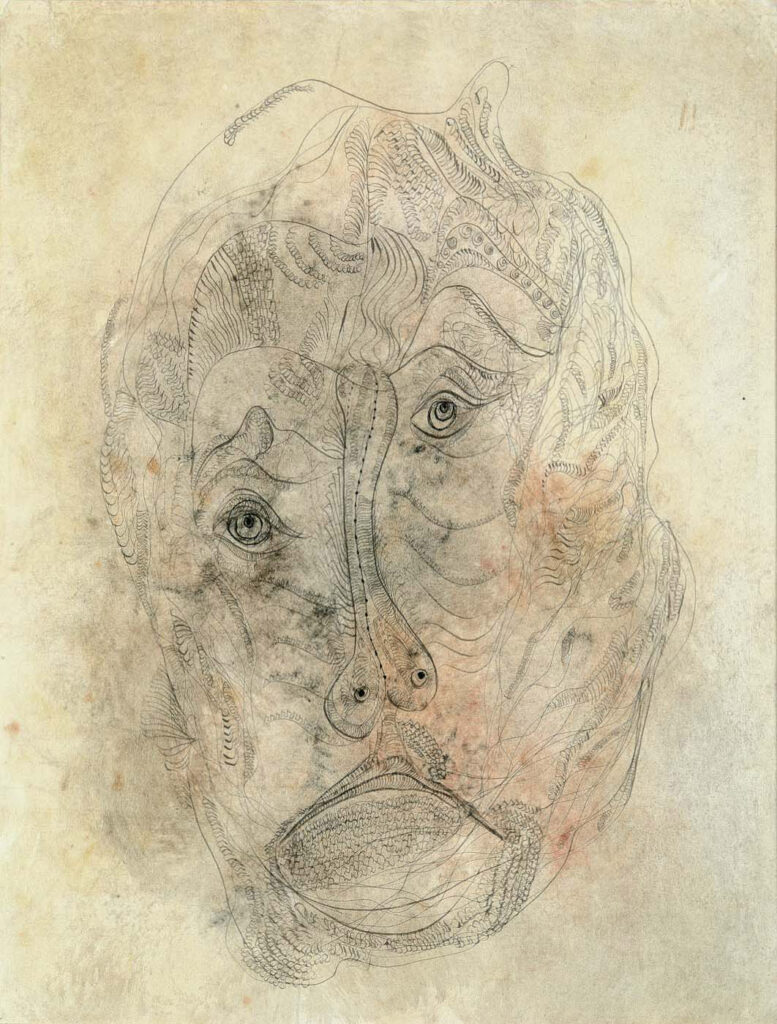

1961.

1965.

1965.

The pen ‘floats’ tentatively above the white paper, until she discovers the spot for the first eye. Only once she is ‘being looked at’ from the paper does she start to find her bearings and effortlessly add one motif to the next.4

Sources

- Unica Zürn, co-written with Hans Bellmer, Letters to Dr. Ferdière (Biarritz: New Editions Séguier, 1994).Cited in Automatic Woman: The Representation of Women in Surrealism by Katharine Conley (Nebraska: The University of Nebraska Press, 1996)

- From a letter published in The Complete Works of Unica Zürn, (Berlin: Brinkman and Bose, 1988-1999). Cited in Dictionnaires et Encyclopédies sur ‘Academic’

- Unica Zürn, The Man of Jasmine, trans. Malcolm Green (London: Atlas, 1994). Cited in: Esra Plumer, “The Comfort of Standing Next to Walls” (Online Publication, 2009).

- Unica Zürn, The Man of Jasmine, trans. Malcolm Green (London: Atlas, 1994). Cited in: Unica Zurn: Dark Spring, curated by João Ribas, edited by Jonathan T.D. Neil and Joanna Berman Ahlberg, Drawing Papers 86 (New York, NY: The Drawing Center, 2009).

3.

BELLMER+ZÜRN

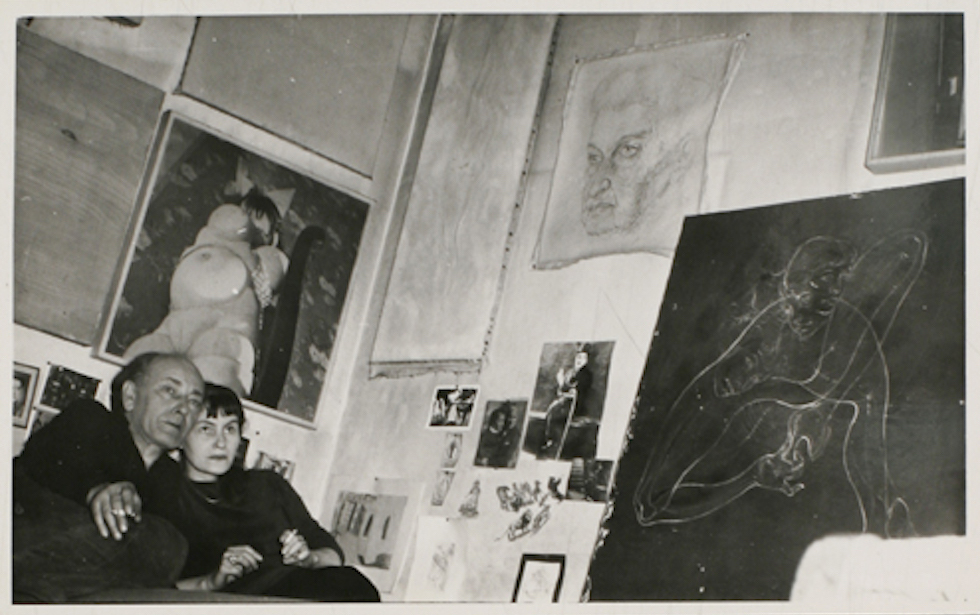

Bellmer and Zürn in their apartment.

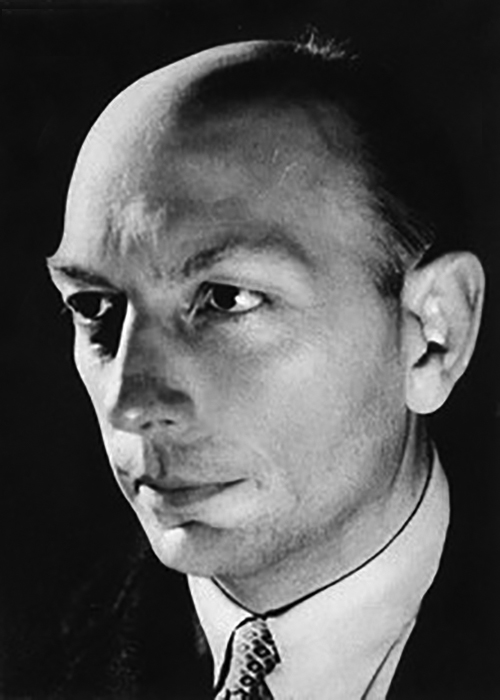

Hans Bellmer

The female body…is like an endless sentence that invites us to rearrange it, so that its real meaning becomes clear through a series of endless anagrams.1

Unica Zürn

If woman is to put into form the ‘ule’ [Greek: matter] that she is, she must not cut herself off from it nor leave it to maternity, but succeed in creating with that primary material that she is […] Otherwise, she risks using or reusing what man has already put into forms, especially about her, risks remaking what has already been made, and losing herself in that labyrinth.2

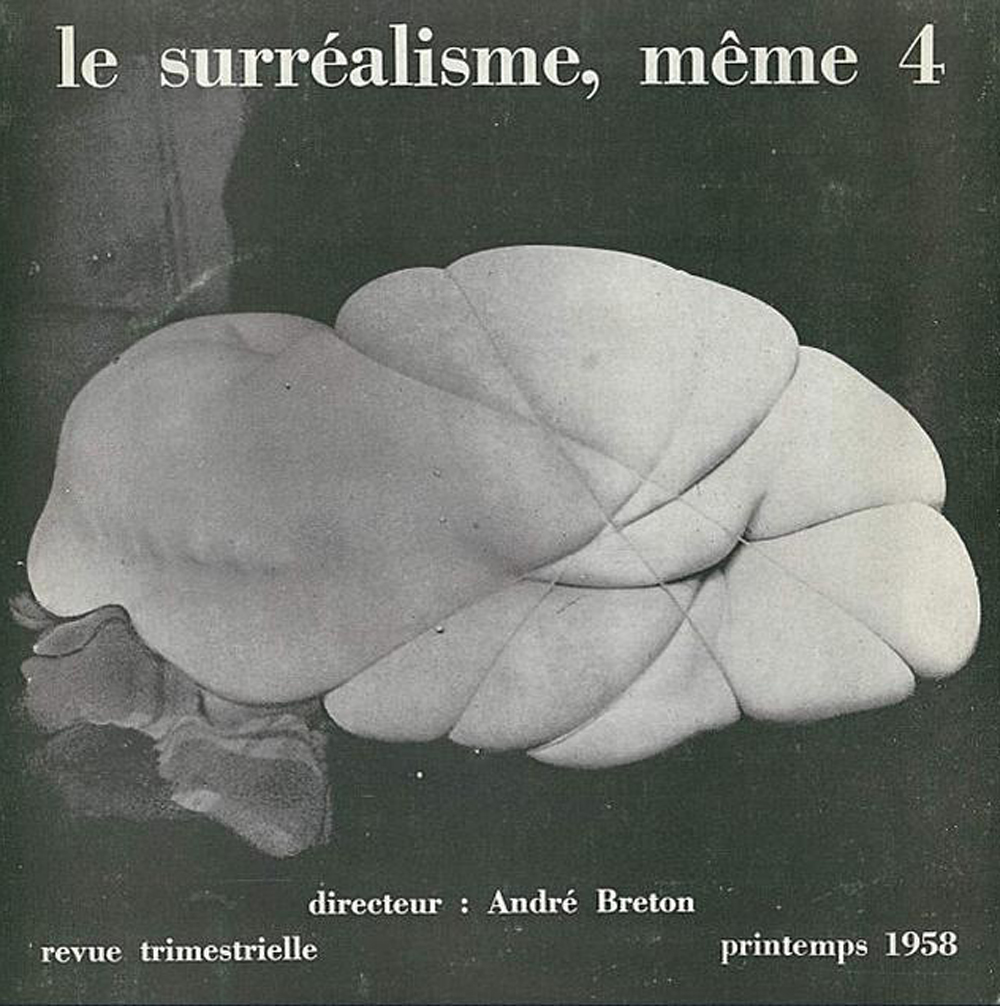

In 1958 Bellmer took photographs of Zürn after wrapping her nude body with twine. It was printed in Le Minotaure and titled “Keep in a cool place.”3

1958.

1958.

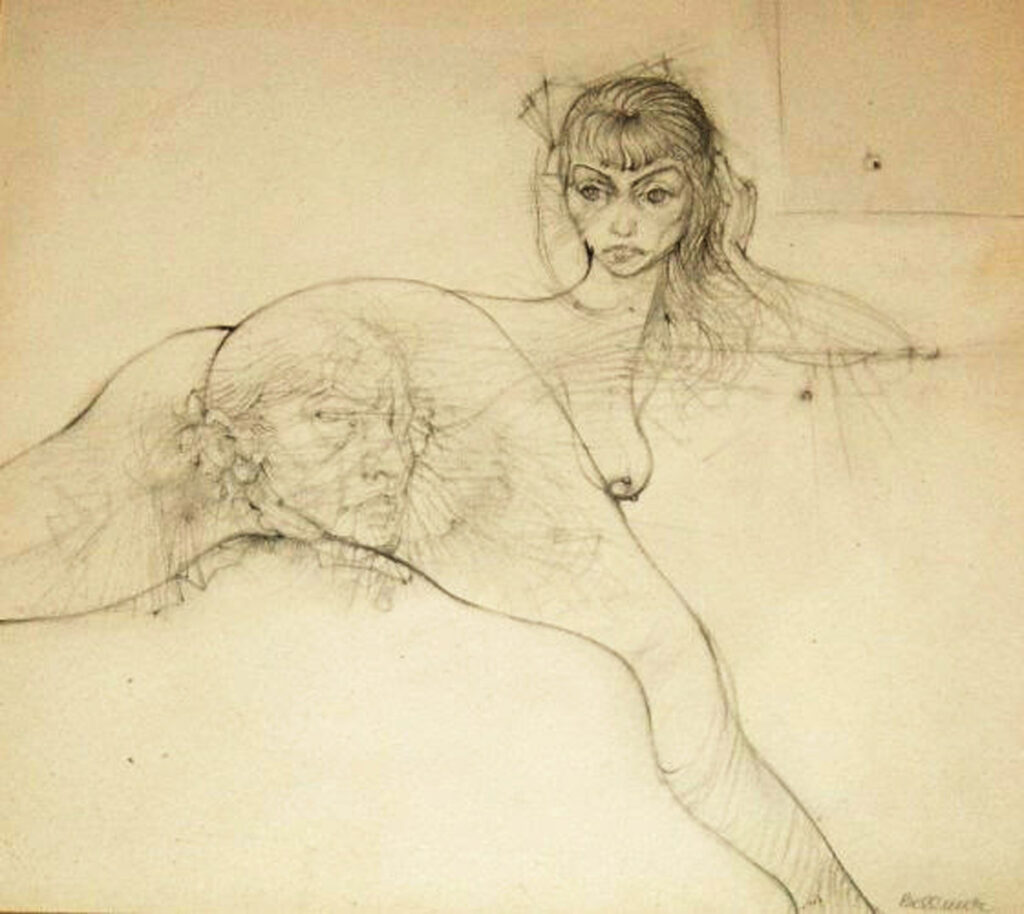

A portrait of Hans Bellmer by Zürn, 1965.

Untitled by Hans Bellmer.

I always need a companion to tell me what to do…They just have to say “now you do this, now you do that.”4

Sources

- Webb P.& Short R., Hans Bellmer (New York: Quartet Books, 1985). Cited in: Miranda Argyle, “Hans Bellmer and The Games of the Doll” (Online Publication, 2004).

- Quote cited in: Subversive Intent: Gender, Politics, and the Avant-Gardex by Susan Rubin Suleiman (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

- Miranda Argyle, “Hans Bellmer and The Games of the Doll” (Online Publication, 2004).

- Unica Zürn, Gesamtausgabe (Berlin: Brinkmann and Bose, 1988). Cited in: Unica Zurn: Dark Spring, curated by João Ribas, edited by Jonathan T.D. Neil and Joanna Berman Ahlberg, Drawing Papers 86 (New York, NY: The Drawing Center, 2009).

4.

ZÜRN, THE WRITER

Hexentexte (The Witches’ Texts), (1954):

“ANAGRAMS are words and sentences resulting from the rearrangement of the letters in a given word or sentence… Man seems to know his language even less well than he knows his own body: the sentence too resembles a body which seems to invite us to decompose it, so that an infinite chain of anagrams may re-compose the truth it contains. At close inspection the anagram is seen to arise from a violent and paradoxical dilemma…What is at stake here is a totally new unity of form, meaning and feeling: language-images that cannot simply be thought up or written up. They enter suddenly and for real into their interconnections, radiating multiple meanings, meandering loops lassoing neighboring sense and sound.”

—Hans Bellmer, Afterword to Hexentexte

• • •

Dark Spring (1970):

It is a very beautiful day. The woman looks around and thinks: “there cannot ever have been a spring more beautiful than this. I did not know until now that clouds could be like this. I did not know that the sky is the sea and that clouds are the souls of happy ships, sunk long ago. I did not know that the wind could be tender, like hands as they caress – what did I know — until now?1

She wants to look beautiful after she is dead. she wants people to admire her. Never has there been a more beautiful dead child.2

She steps onto the windowsill, holds herself fast to the cord of the shutter, and examines her shadowlike reflection in the mirror one last time. She finds herself lovely. A trace of regret mingles with her determination. ‘It’s over,’ she says quietly, and falls dead already, even before her feet leave the windowsill.3

An assessment: “Preadolescent sexuality merges with depressive fantasy—to devastating (if ineffably morbid) effect in this once-notorious novel by a German writer and artist (1916–70) who, like this novel’s young protagonist, took her own life shortly after its (1967) publication. She’s a nameless suburban girl who’s provoked, by her slovenly mother’s indifference, her beloved father’s long absences from home, and her own claustrophobic self-absorption, into masturbatory daydreams and tentative baby steps toward adult sexual expression. The story’s (expertly caught) tone and rhythm are indeed hypnotic … and Zürn caps it with a marvelously bleak, brisk final scene. Unusual and memorable fiction.”4

Sources

- Unica Zürn, Dark Spring (Cambridge: Exact Change, 1970).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Kirkus Reviews, June 1, 2000

• • •

The Man of Jasmine: Impressions from a Mental Illness (1971):

Someone travelled inside me, crossing from one side to the other. I have become his home. Outside, in the black landscape with the bellowing cow, someone is maintaining that they exist. From his gaze the circle closes around me. Traversed by him inwardly, encircled by him from without — that is my new situation. And I like it.1

From the introduction: Zürn’s texts suck one into her world; it is as difficult to break loose as it was for the writer herself. This despite, or perhaps, because of her use of the 3rd person (Zürn’s original manuscript of The Man of Jasmine even attributes the book to “the wife of Hans Bellmer”). Her agency is removed in these texts, like that of the central character, almost as if she has become a medium to her own self. But sometimes she hits back. The Whiteness with the Red Spot, in which she writes in the first person, is a damning condemnation of her contingency, her “training,” the illusions of hope and happiness she had projected onto the other, the man, and in the short texts The House of Illness and in the short Les Jeux a Deux she employs a subversive, laconic humour. Her anagrams even reveal overt aggression…And if her main texts seem strangely subdued by comparison, it should not be forgotten that they were written under a strong inner compulsion, against the advice of others…which jeopardised her ‘normal state.’2

Sources

- Unica Zürn, The Man of Jasmine (London: Atlas Press, 1994). Automatic Woman: The Representation of Women in Surrealism by Katharine Conley (Nebraska: The University of Nebraska Press, 1996)

- Malcolm Greene, introduction to The Man of Jasmine (London: Atlas Press, 1994).

• • •

The House of Illnesses: Stories and Pictures from a Case of Jaundice (1986):

Since yesterday I know why I am making this book: in order to remain ill for longer than is correct. I can slip in a fresh page every day…My better half, which is clever and wise, wants me to remain ill for sometime, for it knows that one can gain from an illness such as mine. My worse half wants me to return to my few duties, yes, feels that it is time for me to show some consideration for my surroundings, which, incidentally, are not large…Perhaps I should now quickly smuggle another couple of empty pages into this book? Forgetting one’s duties has for me the taste of sweet cream.1

A description: Written and drawn during a bout of fever induced by jaundice, The House of Illnesses (Der Haus der Krankenheiten) traverses a kind of mirror world in which happiness is torment, traps are set to improve one’s health, and mortal enemies attack their enemies with virulent love. The narrator’s ailment was caused by her mortal enemy, a sharpshooter whose bullets removed the hearts of her eyes. Her stay in the House of Illnesses is supervised by Dr. Mortimer—adversary, stooge, the embodiment of her “personal death, and ultimately the figure that releases her. Zürn writes at the end of the work that she began the book on the twelfth day of her own illness, Wednesday, April 30, 1958, and she finished it ten days later.2

Sources

- Unica Zurn, The House of Illnessses (London: Atlas Press, 1977).

- Lisa Pearson, introduction to “The House of Illnesses” excerpted in It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists and Writers (Los Angeles: Siglio, 2010) .

• • •

Other Writings:

Pierre Joris translated a few of Zürn’s Anagrams, which can be found on his website:

IN THE DUST OF THIS LIFE

Pale sieves a tired

Ax in the tree’s bosom.

In the foliage’s broom there is

Seed-blood-silk. Bites

in the lovenest of the building.

Sweetly fogs in its ice-bath

the Ibis’s blood. Masses

in the dust of this life.

ONCE UPON A TIME A SMALL

Once upon a time a small

warm iron was alone. No

Noise, no wine let in.

Lightly at the sea ran, while no

Ice was, thrush-pink in a

See-egg. All wink: tear

like all seeds. Sink in,

watergerm, no, alone –

in a pillow. All warmth

once upon a time’s a mall.

Montpellier, 1955

More of Zürn’s anagrams can be found in this excerpt from Anagrams, taken from the complete edition, volume 1 (1988).

5.

ON UNICA ZÜRN

“Zürn’s life reads a bit like a Freudian case study…Zürn was herself equipped with a vivid imagination and, inspired perhaps by Oedipal yearnings, developed a rich interior fantasy life that is evidenced in her later drawings.”

—Valery Oisteanu, artnet

“The muffled scream that issues from Zürn’s drawings is surely the cri de coeur of a woman denied: deprived the love of her monstrously distant mother and the companionship of her absentee father, separated from her two children and refused possession of her own body by its transformation into a pot roast, among other things, by Bellmer. Her revenge is assimilation of the deformities these deprivations caused—her adamant presentation of herself as the twisted and manipulated creature that others have imagined. …Zürn’s virtuosity is that of an artist willing her madness to manifest itself on paper, rather than a mad person exuding symptoms in the form of pictorial expression.”

—Gary Indiana, Art in America

“Zürn’s body of work opens up the interior of a perceptual system of madness. The texts are located at an intersection, a point of transfer. Madness becomes the supplier of literature, literature transports madness. Both drawings and texts show the “image processes” (Zürn) or hallucinations haunting her. “I’m haunted as though I were the only home for something unknown” (4/1:36). It is not she who writes or draws, as images “stream in” or “arise” (4/1:53). A dictation she feels compelled to take down circumvents “sublimated elaboration” (Kristeva). For Zürn, some thing or other–what Lacan calls extimacy (“extimite,” a foreign body, composed of what is intimate)–seems to take charge in the missing place of authorship and sublimation. She is remote-controlled and the rote observer of a delirium that runs on ahead like a movie. She writes down what can be caught. The notes resist, as pure record, the inaccessibility of madness.”

—Rike Felka, The Memorien of Unica Zürn

“For Zürn her body is an imaginary construct, capable of reconfiguration, like the anagrams she loves. This view is in keeping with Bellmer’s contorted dolls, who with their surrealistically flexible body parts represent distorted corporeal anagrams.”

—Katharine Conley, Automatic Woman: The Representation of Woman in Surrealism

“She drew phantasmagoric creatures, chimerical beasts with transparent organs and multiple appendages, plantlike abstractions, oneiric forms, amoebic shapes whose fractal membranes are filled in with multiple recurring motifs: spirals, scales, eyes, dots, beaks, claws, conical tails, leaflike indents. Some early and late drawings are sketches, loose, spare, and barely formed, containing multiple, differentiated, quasi-representational figures; others, often on larger paper, have a more “finished” quality, offering a clear inside to the entity, and an outside expanse of unmarked paper. Another batch, the most depressing, crowd out the picture planes with clusters of Munch-like heads, eyes, and mouths, set against cloyingly patterned backgrounds. These images were produced during one of the frequent institutional internments that followed Zürn’s being diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1960.”

—Bartholemew Ryan, Artforum

“In the art of Unica Zürn, the known is rederranged, the red-eared angel is crushed into a thousand eyes, as if in Tantrik diffraction, cranial shapes break into heads in telescopic profiles, with eye lozenge clusters of hanging pods. Abyss weevils percolate with seed energies.” (from “Unica Zürn” in Reciprocal Distillations, 2007)

see also

✼ ex libris:

“Multiplicity and distance or void wasn’t an affected practice on Johnson’s part; they were the very lenses of his reality.” —Elizabeth Zuba, from her introduction to Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson

[...]