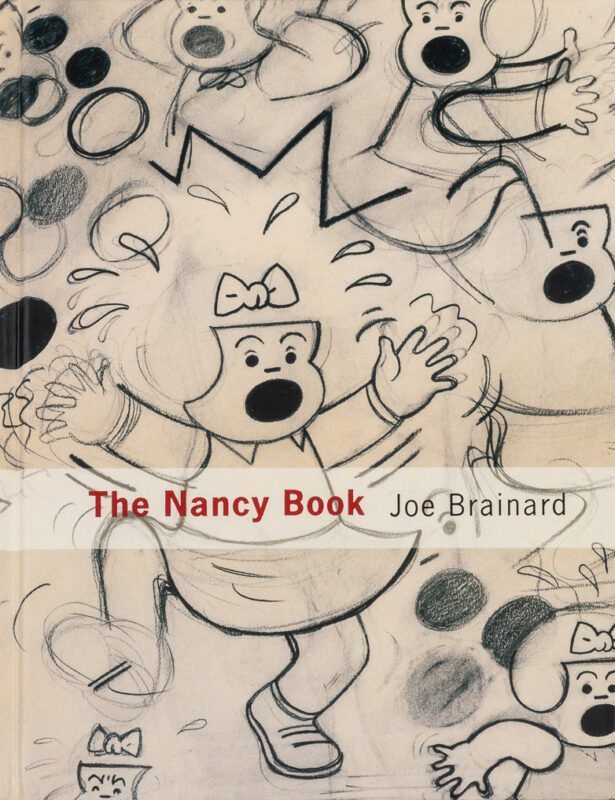

Joe BrainardJohn Ashbery

affinities, 05/01/08

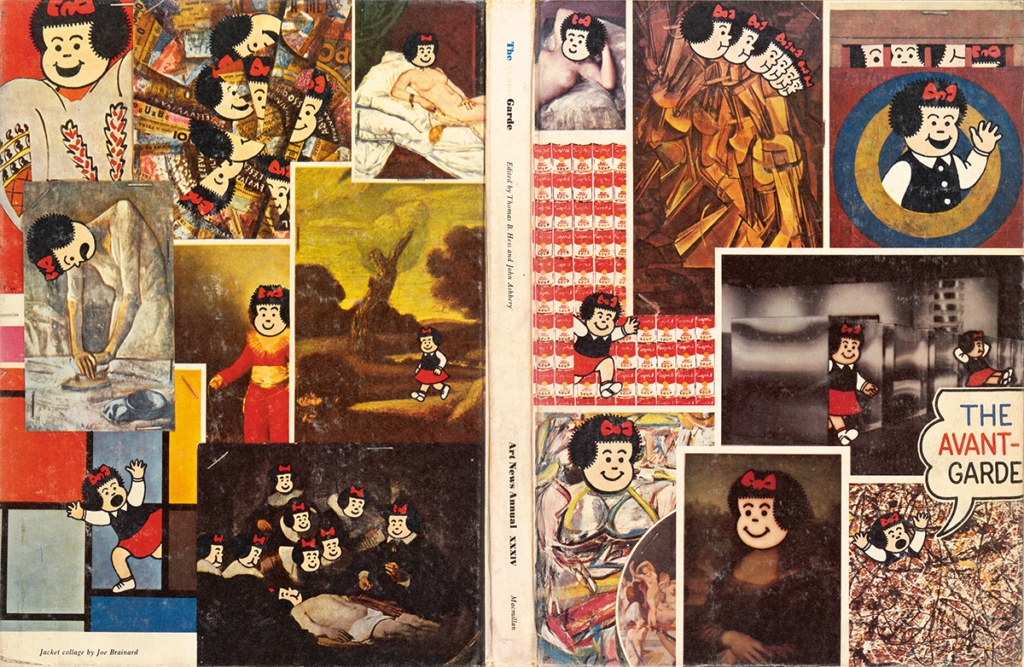

Untitled (“The Avant-Garde”) by Joe Brainard, Art News Annual #34, 1968, reproduced in The Nancy Book

Recently republished in Something Close to Music: Late Art Writings, Poems, and Playlists by John Ashbery, introduction by Mónica de la Torre, selections and playlists by Jeffrey Lependorf (Zwirner, 2022)

Originally published in the catalogue for Joe Brainard: Retrospective, Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York, 1997. Copyright © 1997. All rights reserved. Used here by permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc. for the author.

Joe Brainard was one of the nicest artists I have ever known. Nice as a person and nice as an artist.

This may present a problem. Think of how many artists, especially those whose work you admire, weren’t all that nice. Caravaggio. Degas. Gauguin. De Chirico. Picasso. Pollock. Their art isn’t exactly nice either, but the issue seldom arises. In Joe’s case, it does. He began around the same time that Pop Art did. With Lichtenstein or Warhol there is a subtext of provocation, though the Pop Artists generally were too cool, too “down” as we used to say, to let this possibility become anything more than unspoken. In Joe’s work, one of his pictures of pansies, for instance, there is confrontation without provocation. A pansy is a loaded subject. So is the effortless, seed-packet look of the painting. But there’s no apparent effort on the artist’s part to cause stress or wonderment in the viewer. With Joe, a certain gratitude mingles in the pleasure he offers us. One can sincerely admire the chic and the implicit nastiness of a Warhol Soup can without ever wanting to cozy up to it, and perhaps that is as it should be, art being, art, a rather distant thing. In the case of Joe one wants to embrace the pansy, so to speak. Make it feel better about being itself, all alone, a silly kind of expression on its face, forced to bear the brunt of its name eternally. They we suddenly realize that it’s “doing” for us, that everything will be okay if we just look at it, accept it and let it be itself. And something deeper and more serious than the result of provocation emerges. Joy. Sobriety. Nutty poetry.

There are however no histoires à l’eau de rose here. Nor is Joe’s book of “remembers” for family viewing. Some indeed seem to require a new rating for “humane smut” though they are so cleverly interleaved among others like “I remember wondering if I looked queer” and “I remember the rather severe angles of ‘Oriental’ lampshades” that one can’t say for sure. One is “taken aback.” The writing and the art are relaxed—not raging—in their newness, careful of our feeling, careful not to hurt them by so much as taking them into account. They go about their business of being, which in the end makes us better for having send and lived with them; and better for not feeling indebted to them, thanks to the artist’s having gone to unusual lengths for us not to feel that.

Joe was a creature of incredible tact and generosity. He often gave his work to his friends, but before you could feel obliged to him he was already there, having anticipated the problem several moments or paragraphs earlier, and remedying it while somehow managing to deflect your attention from it. Into something else: a compassionate atmosphere, where looking at his pictures and recognizing their references and modest autobiographical aspirations would somehow make you a nicer person without realizing it and having to be grateful. It’s for this, I think, that his work is so radical, that we keep returning to it, again and again finding something that is new, bathing in its curative newness. Joe seems to have taken extraordinary pains for us not to know about his work. Either he would create 3,000 tiny works for a show, far too many to take in, or he would abandon art altogether, as he did for the last decade of his life, consecrating his time to his two favorite hobbies, smoking and reading Victorian novels. It’s as though in an ultimate gesture of niceness he didn’t wasn’t us to have the bother of bothering with him. Maybe that’s why the work today hits us so hard, sweeping all before it, our hesitations and his, putting us back in the place where we always wanted to be, the delicious chromatic center of the Parcheesi board.

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

august 27, 2024—Oh, the chasm of meta. First, hackers hacked the original @sigliopress. As we refused to pay the ransom and meta was zero to nothing with help, @sigliopress disappeared into the abyss. A brief attempt at another—@sigliopress_affinities—was deemed “inauthentic” and taken down by meta, with none of the recourse supposedly on offer actually available. What now? Who knows. The point is…? Alas.

[...]