“photography, discretion, instinct and appetite”Odette England, Photo-Eye

reviews, 11/08/21

You shouldn’t invite me to a dinner party. I mean, I’m a reasonable guest. I arrive on time, bearing something nice (flowers, wine, dessert, pet treats). I offer to help serve or dry the dishes. I have a non-offensive laugh. You can seat me on the upside-down trash can that doubles as a spare chair, I won’t complain. I also know a few two-drink-minimum party tricks, like applying lipstick using only my breasts. But when I go to the restroom, my inner spy manifests: I will inspect the contents of your medicine cabinet.

Why? Because that’s where your uncensored life is. It’s one of the few concealed spaces of a home I can access without detection. Peek at a private version of you, presented in rows with reasonable lighting, revealing much more than your refrigerator. Your birth control preferences, meds you’re taking; wow, you use that brand, yeesh… I check out your stuff and draw conclusions. I know you know: it’s estimated almost 40 percent of folks admit that they put things away before guests arrive. Good thing, too; otherwise I’ll treat myself to a spritz of that classy perfume, thank you so much. It’s also a project I thought about as a student: thrusting my Speedlite into the shallows of friends’ little cupboards, then using their surnames or addresses as captions.

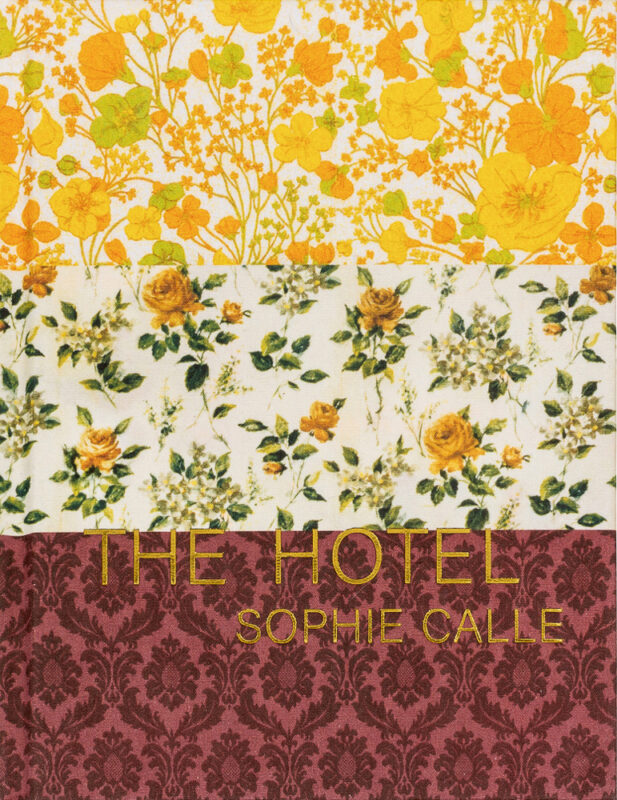

Few would do more justice to such a project than Sophie Calle. The only photographer I’d invite to stay with me long-term to see her take, in words and pictures, on the unflattering reality of my life. Remember in 1999 when the world gave birth to the Big Brother franchise? John de Mol Jr. missed an opportunity by not inviting Calle to direct what would become the biggest reality competitions on the planet. Though, it’s more fun to think of Calle turning down the offer. She has already syndicated her creative genius in more persuasive, compelling ways. One being her latest photobook The Hotel, first included in the 1999 book Double Game (long out of print). Now, a single standalone book and available in English for the first time.

The first spread is a black-and-white image of a bed. The book’s gutter separates left side from right. There are two pillows top of frame, then a sheet, wrinkled and turned down; then a patterned stained bedspread. Along the bottom of the page the text reads: On Monday February 16, 1981, I was hired as a temporary chambermaid for three weeks in a Venetian hotel. I was assigned twelve bedrooms on the fourth floor. In the course of my cleaning duties, I examined the personal belongings of the hotel guests and observed, through details, lives which remained unknown to me. On Friday March 6, the job came to an end.

It may seem Calle is giving the game away. Far from it: The Hotel becomes spicier and weirder with every page turn.

Let’s pause to consider Monday February 16, 1981, two days after Valentine’s Day (when almost a third of cheaters have affairs in hotels). Calle is 28 years old. A hand grenade explodes and kills the man carrying it at a stadium in Karachi, before Pope John Paul II arrives to celebrate mass with 70,000 people. It’s the year Ronald Regan is shot, Kiev’s Motherland Monument opens, and The Smurfs make their television debut. People are listening to Dolly Parton’s 9 to 5 on the radio. It’s also International Pancake Day. Why does any of this matter? This is a sliver of the backdrop to which Calle pokes her lens and pen into the lives and suitcases of strangers whom she is entrusted to clean up after. It provides some context, and context is everything.

Now for some theories about hotel land. The TV remote control is the dirtiest object in your room. Big suitcases mean high-maintenance guests. Never use the decorative cushions; they spend most of their lives on the floor. If you leave out your expensive shoes, they will be Cinderelled (yes, borrowing guests’ clothes happens outside of films like Maid in Manhattan). Oh, and having a fourth floor in a hotel is bad luck, a bit like a gate thirteen at an airport.

There are twelve color images positioned at intervals in The Hotel, full-bleed portraits of the beds in each of the rooms assigned to Calle. They are frontal, formal, clinical photographs. Beds made, the perspective direct. Everything is in its place. Each followed by a black and white photograph of an opposing view. Beds are now messy, angles off-kilter. Neatness replaced with the creases of cuddles, courtship, and conversation. On the next page, we’re given the room number and dates of occupancy, followed by seesaw arrangements of Calle’s adroit storytelling. It’s here the content hovers between police report, diary, press photo caption, missing cat poster, home shopping network catalog, photocopy log, and medical invoice. In short, a genre all its own.

Combining image and text well in a photobook is tricky. Calle is a master. Neither triumphs over the other. Calle takes to words like a surgeon wielding a favorite ten-blade. Each sentence is a balance between rudimentary and essential. So too with her camera. I feel Calle’s gaze touch every object. I hear her inhale the musty smell of the hotel iron that has infected your poly-cotton shirt. Her lips so close to its collar she can almost taste its texture. All the while she unravels, labels, authenticates her version of your life in the starkest, most enchanting minimalism.

Continue reading at Photo-Eye

see also

✼ elsewhere:

“In my opinion, genre is a way of speaking about conventions of reading and looking, where you sit or stand and whether you’re allowed to talk to other people or move around while you’re communing with an object or text.” —Lucy Ives, from her interview with Karla Kelsey in Feminist Poetics of the Archive at Tupelo Quarterly

[...]