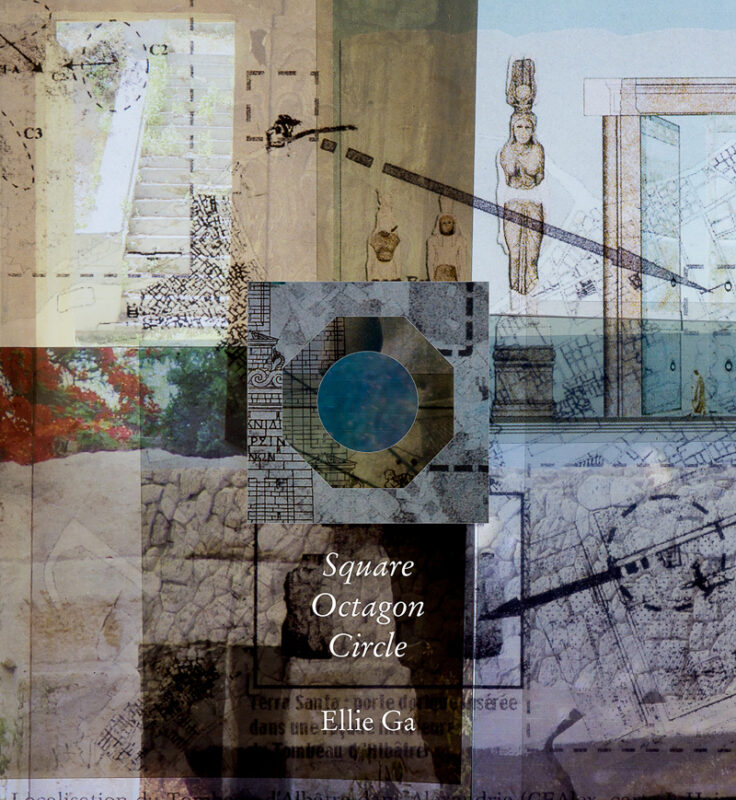

In Praise of DriftIn conversation with Ellie Ga, artist of the intrepidAnna Della Subin, Tank Magazine

features, 06/27/19

Ellie Ga is an artist of the intrepid. Charting a course from Patagonia to the North Pole, she voyages through histories, mythologies and languages, navigating the role of the artist on a precarious planet. Her points of latitude are chance meetings, accidents and coincidences. At her longitude are archives, libraries and ethnographic museums, filled with decaying relics of discovery.

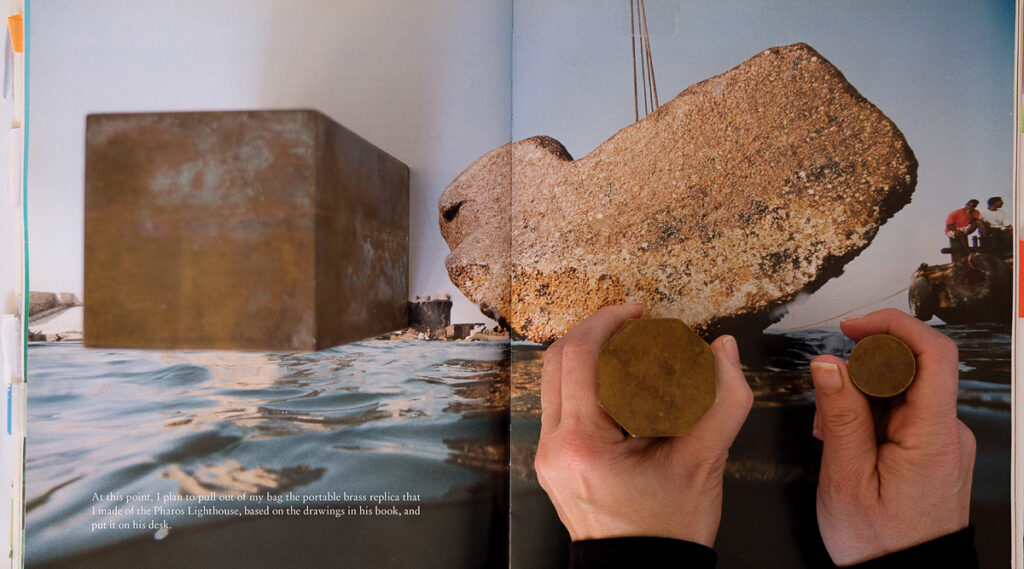

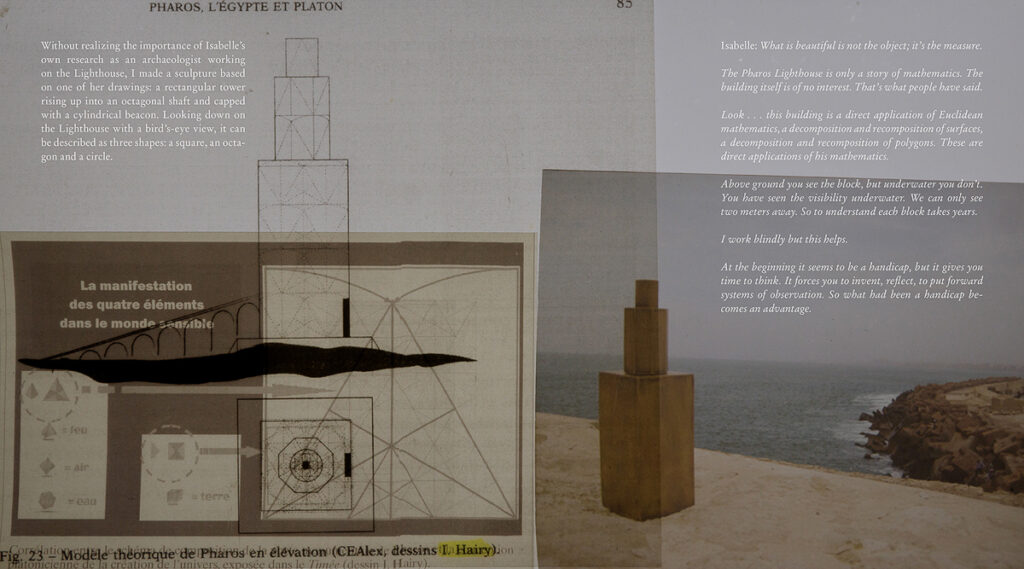

A statue is lifted from the sea, Alexandria, from Ellie Ga’s Square Octagon Circle.

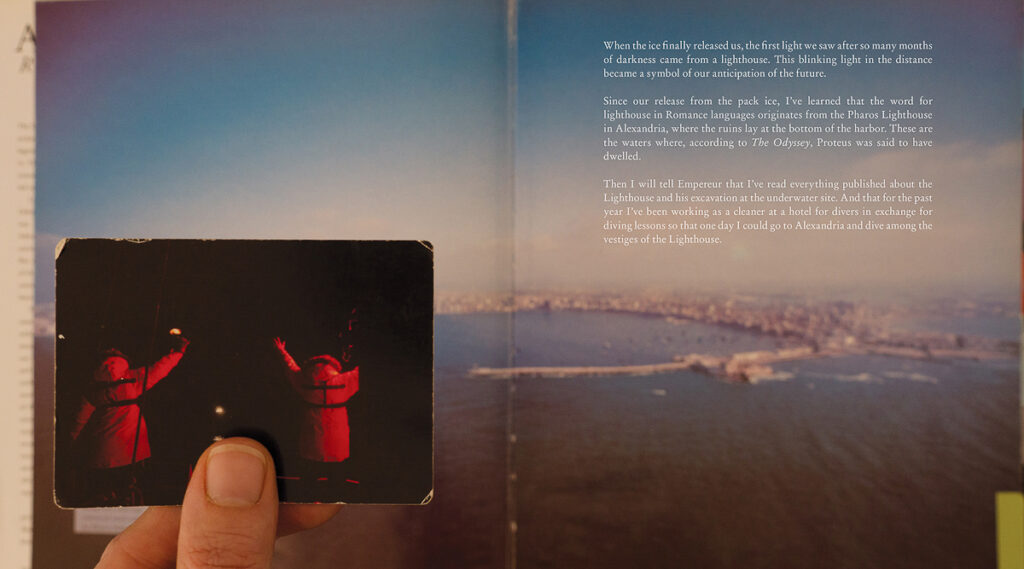

Archaic scriptures and modern poets guide her to lost places. In 2007, Ga was artist-in-residence aboard the sailboat Tara on an expedition to collect scientific data on climate change at the North Pole. She joined the boat after the Tara had been frozen into the polar cap for 13 months and stayed for the final five months before it floated free. Trapped in the ice in the Arctic darkness, the ten-person crew had no idea for how long the boat would drift. They were at the mercy of the melting ice to bring them home, an experience Ga captured in The Fortunetellers, a multimedia series of videos and performed essays, diaries, travelogues, sketches and ephemera. The first light they saw in the dark came from a lighthouse off the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, which inspired Ga’s next investigation, of the Pharos lighthouse off the coast of Alexandria, Egypt. First built by Ptolemy in 280bce and one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, it was destroyed in the 14th century by an earthquake and now lies as a pile of 2,419 stones at the bottom of the Mediterranean. Not long after the popular uprisings of 2011 began in Egypt, Ga arrived in Alexandria to study marine archaeology and learned to scuba dive. She observed politics above and below the water, as she swam through the ruins ever threatened by the Egyptian government’s attempt to build a concrete breaker around the city. Ga has published two new books in 2018: Square Octagon Circle, an exquisitely layered excavation of the sunken lighthouse and her own Egyptian quest, and North Was Here, a collection of her journals from the Arctic. She currently lives in Stockholm, where she is working on, among other projects, a history of the message-in-a-bottle. We met in New York in late July in the West Village, and talked of explorers and occultists, fossilised sloths and drowned antiquities, to the ambient clatter of oyster shells on ice.

Anna Della Subin

What was it like living for so many months in polar night?

Ellie Ga

I felt that all the details became so brilliant in the dark. There was no visibility – unless there was a full moon, your universe was just what was very near to you. So you fixate on certain objects. For me, the fixation was on etymologies and mythologies. I began to interpret the roles and gestures of everyone on the boat through the lens of myth. It struck me how myths are invented when you have a limited knowledge of the natural world; you have to find reasons why there’s thunder, lightning or an earthquake. Aboard the Tara, we had very little contact with the outside world. There was an iridium satellite phone that we were able to use to call people, and once a day, the phone was connected to the Tara’s laptop to retrieve emails as plain text. If we needed to find out information, we had to write an email to a friend asking for it. We couldn’t surf the web. I became obsessed with the etymology of the word “yo-yo”, and it took weeks to find out. As we drifted towards the ice edge and the boat was released, we began to sail on the open sea. The first light we saw, three days later, came from a lighthouse. Because it was a French expedition, I had been studying French, and began to wonder, why is the lighthouse called le phare? If I had had the internet, I would have found out within minutes, and that would have been the end of it. But for me the darkness led to a great curiosity where things fester and become larger than life. The other thing, of course, is that it makes you more sensitive and paranoid. As the winter went on, every week a different crew member really annoyed me! And that had to have been a product of the darkness.

The crew of the Tara saluting the lighthouse, from Ellie Ga’s Square Octagon Circle.

The Isabelle Hairy plan for the Pharos lighthouse, from Ellie Ga’s Square Octagon Circle.

ADS

In the footage captured in The Fortunetellers, there is something utterly terrifying about the sound of the ice cracking and breaking in the dark…

EG

It felt like a wild beast emerging from the ice. But I have to say, as the artist on board, I was privileged. While I could record the sounds and interpret them in mythological ways, the captain’s job was to make sure the ice wasn’t going to damage the boat, leaving us shipwrecked.

ADS

Had the boat been on a similar expedition before?

EG

The Tara was purpose-built to drift in pack ice, but had never done it before. It was built in the 1990s by a French explorer, who then lost all his money and had to sell it. It was bought by Sir Peter Blake, a New Zealand yachtsman, who used it for educational work. But then, in 2001, he was murdered in the Amazon.

ADS

He was murdered on the boat?

EG

Yes. And so Blake’s widow sold it; she obviously wanted to get rid of the boat right away. But because it was built to drift in pack ice, it had a very odd shape. Almost like an olive pit made of aluminium. If you squeeze it between your fingers, it pops out. The widow sold the boat to Étienne Bourgois, the son of the French fashion designer Agnès B., who wanted the boat to fulfil its original purpose. Only one previous expedition had drifted in the frozen Arctic, that of the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen in 1893. At the time, people still believed in this open polar sea, which, sadly, will soon be a reality. For centuries, people thought that if they could only get past the ice, they would reach this warm, tropical place at the North Pole. The ancient Greeks had the idea of the Hyperboreans, a race of giants who live beyond the north wind in perpetual sunlight. And of course, if you go a little bit farther, you can get to the hollow Earth, if you’re really out there, you know?

ADS

Find the Lemurians or whoever’s in there!

EG

Exactly. That was all the rage in the US in the 1880s… Nansen was a great polymath. He had heard of the ill-starred voyage of the USS Jeannette, which set off in 1879 to reach the North Pole. The boat became trapped in the Arctic ice and was smashed to pieces by the pressure.

A few of the sailors survived by walking across the pack ice into Siberia. Some of the flotsam and personal effects from the boat ended up on the other side of Greenland, which for Nansen was proof that the frozen ice still has current and drift – it was still an ocean. The relics of Jeannette had travelled over the top of the world. For Nansen, these objects were, in a way, messages in bottles, that he interpreted. They spoke about, and over, the distance – and they led him to prove a scientific theory that no one believed. You know how, sometimes, people just haunt you? Many years later, in 2016, I was volunteering in Lesvos in the refugee camps, at a time when the laws governing the EU borders kept changing. And I met older Greeks, who told me stories of their parents arriving on boats from Smyrna in 1922, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. I visited a remote refugee museum in Skala Loutron, which housed objects that people carried with them when they fled. In one of the vitrines was a Nansen passport. I had completely forgotten, but at the end of his life, Fridtjof Nansen was High Commissioner for Refugees at the League of Nations, and passports for stateless peoples were named after him. It was the first moment of the institutionalisation of refugee status. So there was Nansen again. And for him it all began with debris on a beach in Greenland.

Continue reading at TANK.

see also

✼ affinities:

“I can not understand how you … would publish such filth. The book cost $39.95. This was not works of art.”

[...]