Taming DragonsA Conversation with Nicole RudickSam Stephenson, Air/Light

features, 11/01/22

Originally published in Issue #7: Winter/Spring 23

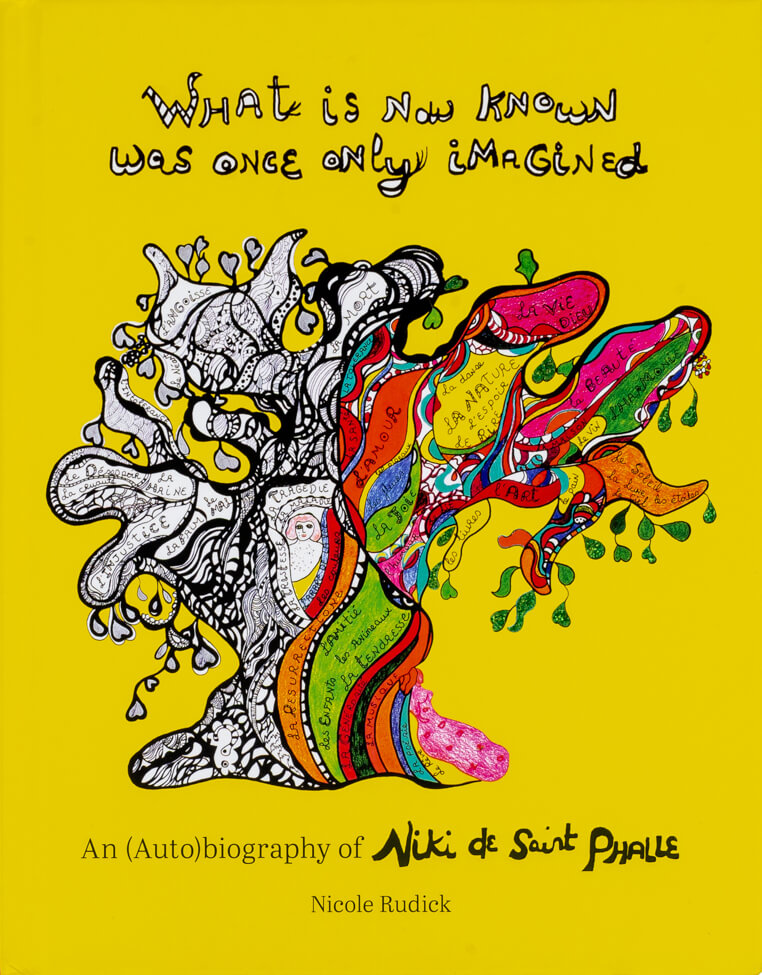

Nicole Rudick’s What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined: An (Auto)biography of Niki de Saint Phalle (Siglio Press) is a hybrid: both a biography and autobiography of the artist, told in images and words.

The Museum of Modern Art once described Saint Phalle’s output—which ranges from sculpture gardens to prints to theater sets to jewelry—as “overtly feminist, performative, collaborative, and monumental.” Rather than explain Saint Phalle, Rudick chose instead to work with a trove of rare and previously unpublished writing, letters, paintings, drawings, sketches, and other works on paper from the artist’s archive in Santee, California, and sequenced these materials without analysis or interpretations. The result is an intimate account of Saint Phalle’s life and creative concerns and an unconventional, utterly unique mode of life writing.

I first met Rudick in 2011 when she was managing editor of The Paris Review. We worked together on several dozen online pieces, including the Review’s first excursion into mixed media, a thirteen-part series called Big, Bent Ears. The collaboration influenced my book Gene Smith’s Sink, which is informed by our ongoing, open-ended conversations about the mysteries of life writing.

Rudick and I spoke via Zoom about her two decades of interest in Saint Phalle, why a traditional structure didn’t fit the subject, and the historical lack of women’s voices in the fields of biography and autobiography. — Sam Stephenson

sam stephenson

When did you first come across Niki de Saint Phalle’s work?

nicole rudick

It must have been sometime when I was in high school or college. I was reading about somebody else when her name came up. She was French and I loved French things, and I must have seen a Nana, or something related to the Nanas, which are all about women and brightly colored—so she brought together all of the things I was interested in. Her work has been on my mind ever since then.

ss

Did you know the whole time that one day you would write about her?

nr

I didn’t know. It took me a long time to understand that I could think about art in this way. I grew up in Denton, Texas, and my mother worked in Fort Worth, near the Kimbell Art Museum, the Amon Carter, and the Science and History Museum. Whenever my sister and I would go to work with her, she’d take us across the street to the museums, especially the Kimbell, which is one of the best small art museums in the country. Louis Kahn designed the building. It’s a series of concrete barrel vaults with diffused natural light coming through skylights and huge concrete slab doors. Lots of travertine and white oak. It feels like a tomb—in the best way possible!

Seeing art there was most definitely formative. I remember seeing the Barnes collection, a show of Jain art, the Terracotta Army, work by Noguchi, Georges de la Tour, Old Masters. I was obsessed with Impressionism and post-Impressionism for a long time. But when I went to college, it never occurred to me that art was something I could study. I took my first art history class when I was a junior, and it was a revelation.

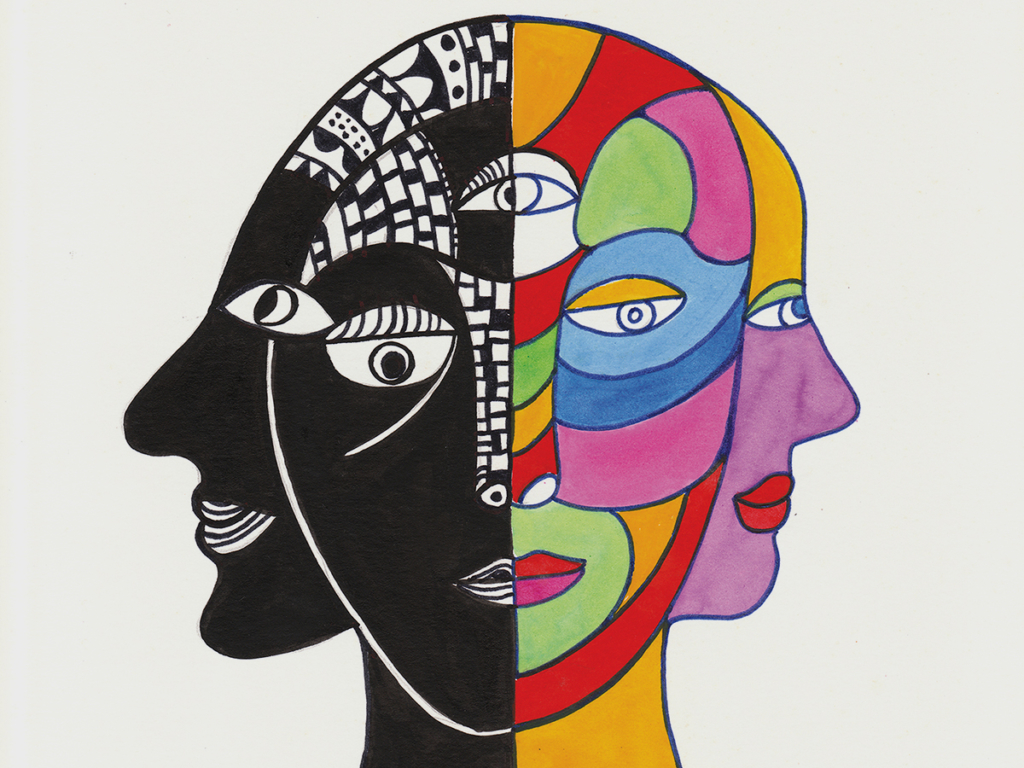

I moved to New York after college and got my master’s in art history at Columbia. I worked at Artforum and Bookforum for about eight years and never came across Saint Phalle’s work. It wasn’t until I was at The Paris Review that I saw her work in a back issue. In 1969, the Review published one of her “Dear Diana” drawings, thanks to their Paris editor at the time, Maxine Groffsky. It combines image and text, which is a form I’ve written a lot about, and being reminded that she worked in this way got me thinking about her art from a biographical point of view.

ss

I’m interested in your focus on primary documents.

nr

Archival materials, interviews, artist writings—that’s where I always start. That’s where I am most comfortable. In college—I went to Trinity University, in San Antonio—the emphasis in art history was on primary documents, not theory, and on analyzing the form of a work of art. Those approaches have really stuck with me. Columbia introduced me to theory, and I used those ideas for support, but theory is never primary for me.

ss

When did the idea for this book arise?

nr

It began to take shape around 2015 or 2016. I had enough of a sense of her works on paper that I knew they were deeply and intimately autobiographical, and I thought there were enough of them to tell her story. When I went to Saint Phalle’s archive, outside San Diego, I found many other things—unpublished writing, serial drawings that addressed her inner life, rarely seen autobiographical works on paper. It was more than I’d hoped for. And that’s also when I realized I didn’t need or want to include anyone else’s commentary. Her voice in these works was so present, so strong.

ss

How had you imagined including commentary?

nr

I had thought that I would supplement her material by interviewing friends and family of hers, to fill in the gaps or offer insights. But in the archive, I read through a binder full of just these sorts of interviews that were done after Niki’s death and realized that, as would be true with anybody, if you ask someone about a person, and then ask someone else about the same person, you get two different stories, two different people. I mean, you know this from working on your biography of Gene Smith. Who knows the truth of a subject? Is there ever a truth of a person? I realized that each of these people who had been close to Niki saw something different in her. I didn’t want that in the book. Her voice was so strong in the artwork and writings she left behind and that was enough. I wanted to tell the story from her point of view.

ss

The word you use in your introduction to describe interviews with people who knew Saint Phalle is “claim.” They were all making claims about her. They were claiming her, not letting her be.

nr

They were claiming some sort of truth about her. My intent isn’t to denigrate or disparage those people or to imply anything malicious. It can’t be helped. We behave differently around different people, and that produces different versions of ourselves. It’s like “phone voice”—when you get on the phone, you talk differently from how you do off the phone, and it depends on who you are talking to as well. Two people may understand you in very different ways.

As we age, we change too. I’m not the same person I was twenty years ago. That person is still in me, but if you had interviewed me twenty years ago as opposed to interviewing me today, I would be quite different. That’s an idea worth pursuing, but it’s not exactly how I wanted to approach this book.

ss

You let Saint Phalle’s words and drawings tell the story and it makes them explode off the page. As I read, I thought: In a normal book, the author would jump in at this point and connect some dots and add commentary, but if you had done that, it would have diluted the power of Saint Phalle’s art. It takes a gifted and brilliant person like Saint Phalle to leave behind documents with that kind of power, but then the decision to take yourself out of the presentation indicates such a lack of ego on your part. Did you and Lisa [Pearson, publisher of Siglio] discuss this approach from the outset?

nr

I knew Lisa was the only editor who would let me do it this way. It’s characteristic of her entire endeavor. It’s hybrid, neither one thing or the other—that’s the realm where Siglio functions. She immediately grasped what I had in mind and wanted to publish it, without hesitation. She never doubted my approach. Her confidence helped keep me going because I have to admit there were times when I didn’t know if the book was going to hold together.

Ruth Scurr’s unusual biography of the seventeenth-century writer John Aubrey is the closest model, and I kept her book on my desk during the entire project. Whenever I had doubts, I would pick it up and read a few pages and feel I could keep going. It was a talisman for me. It was hard not to insert my opinions into the book, to analyze Niki’s work, because I do have opinions about it, but I knew this book wasn’t the place for those opinions.

ss

The book opens with an insightful letter that Saint Phalle wrote to her mother. It’s stunning on one hand and electrifying on the other because, as a reader, you realize you are dealing with something unusual.

nr

I believe that’s who she was. She wouldn’t have made the art she did if she weren’t someone who was capable of thinking intently about her own feelings. The monumental sculptures and sculpture parks took an incredible amount of will and desire to create, and yet throughout her career, she was invested in collaboration and inclusion. She was not egotistical but also did not negate herself. That’s a fascinating balance . . .

see also

✼ the improbable:

from Issue, No. 1 (Time Indefinite), “Dick Higgins, Publisher: Notes Toward a Reassessment of the Something Else Press Within a Small Press History” by Matvei Yankelevich: “To find connections between poetry, small press publishing, and the art scene of the early 1960s, one may look no further than Higgins’ own network.”

[...]