Dick Higgins, PublisherNotes Toward a Reassessment of the Something Else Press Within a Small Press HistoryMatvei Yankelevich

the improbable, 09/17/23

Originally published in The Improbable, No. 1: Time Indefinite, Siglio, 2020. All rights reserved. © 2020 Matvei Yankelevich. Reproduced with permission.

It is no surprise that the democratizing movements of small press and artists book publishing attained political consciousness and blossomed alongside—and in direct proportion to—the social and cultural upheavals of the 1960s and early 1970s. What is surprising is that they are rarely talked about in the space of the same paragraph or the same page or even the same book in most print culture histories.1

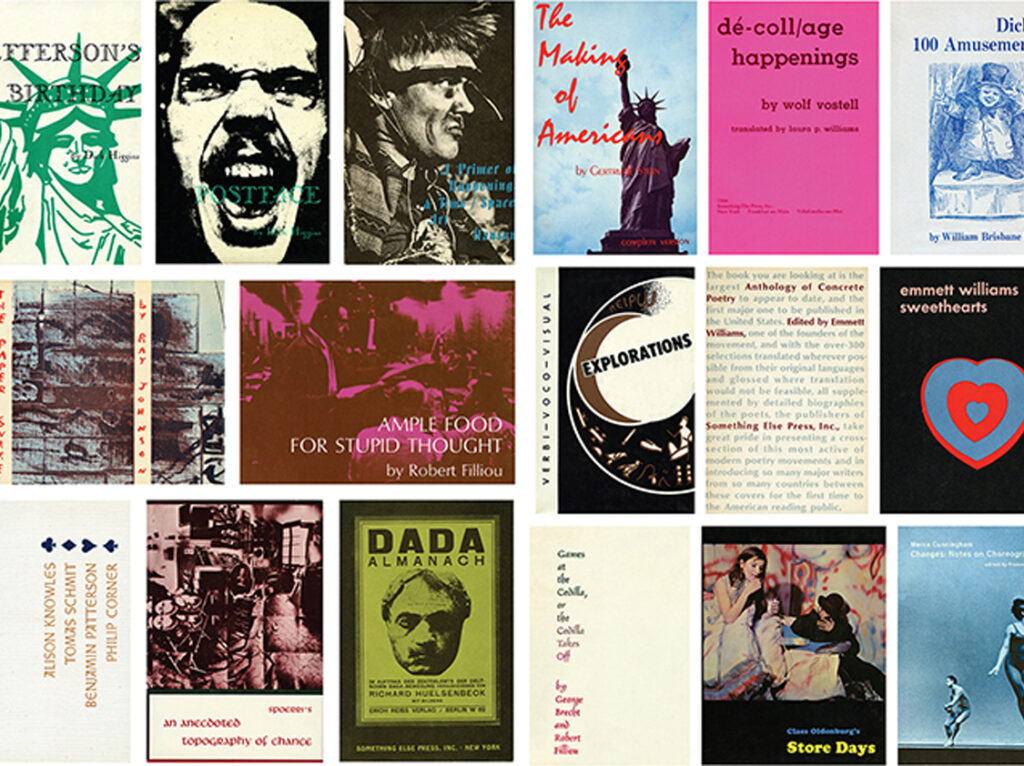

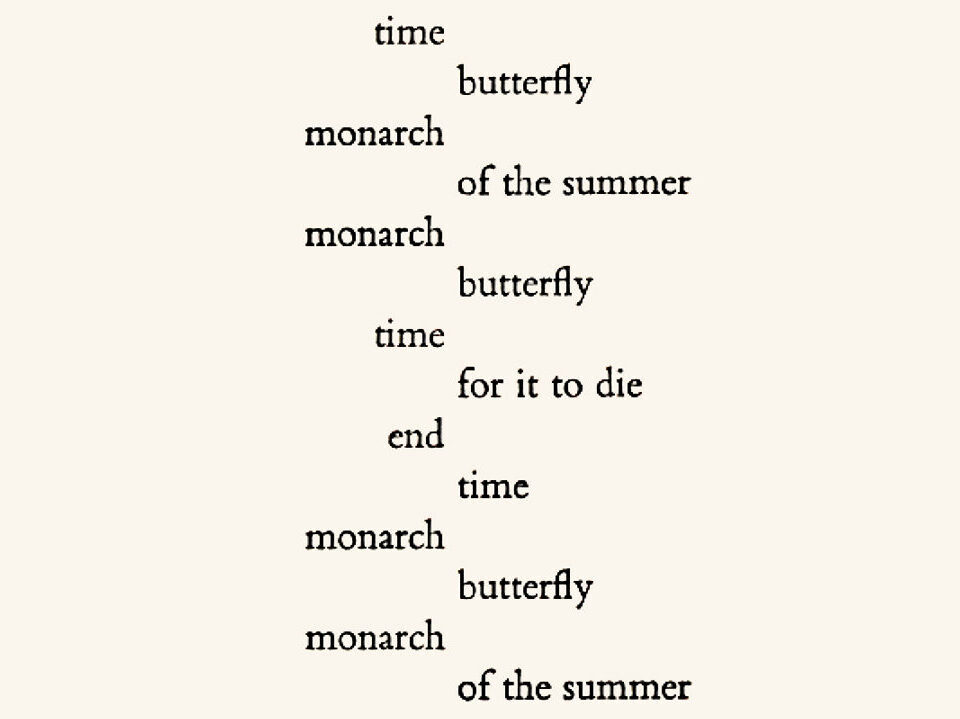

Dick Higgins’ the Something Else Press (1964-1974) questioned the very distinction between between literary small press publications and artists books, even before the latter term was formulated. Higgins’ refusal to disentwine literature from art, both in his own work2 and within the context of SEP (and later) publishing projects, is in line with his conceptualization of intermedia, and his belief in the book as an information technology which could disturb and lastingly alter—or at least offer a corrective to—late western culture’s divisions between the arts.

Similarly, SEP troubled another distinction, the divide between commercial or “trade” publishing and the small press field of operations. The question of where to place SEP along the publishing continuum is entangled in histories now obscured by its legendary status. Beside the question of whether SEP was an art publisher, an artists book press, or a literary press—a publisher of “freak lit” as Higgins once called it—there is the question of its organizational structure and principles. It has been characterized diversely both by its historians and those who worked under its roof. Higgins himself vacillated. He frequently formulated SEP’s mission as directly counter to what “normal” publishers would take on,3 while also differentiating it from Maciunus’s Fluxus editions (or “object books”4) as an “outreach series, useful for getting our ideas beyond the charmed circle of cognoscenti […] one which could present to the larger public all kinds of alternative and intermedial work.”5 (In other words, SEP was what we might now call a “mission-driven” publisher.) In the late 1970s, Higgins came to the conclusion that it was “a mistake on a […] profound level to try and do such unconventional books with unconventional and heavy-cultural implications, while using a thoroughly conventional organizational structure.”6 In 1992, he wrote that it faced all the problems “typical of […] any small, independent press.”7

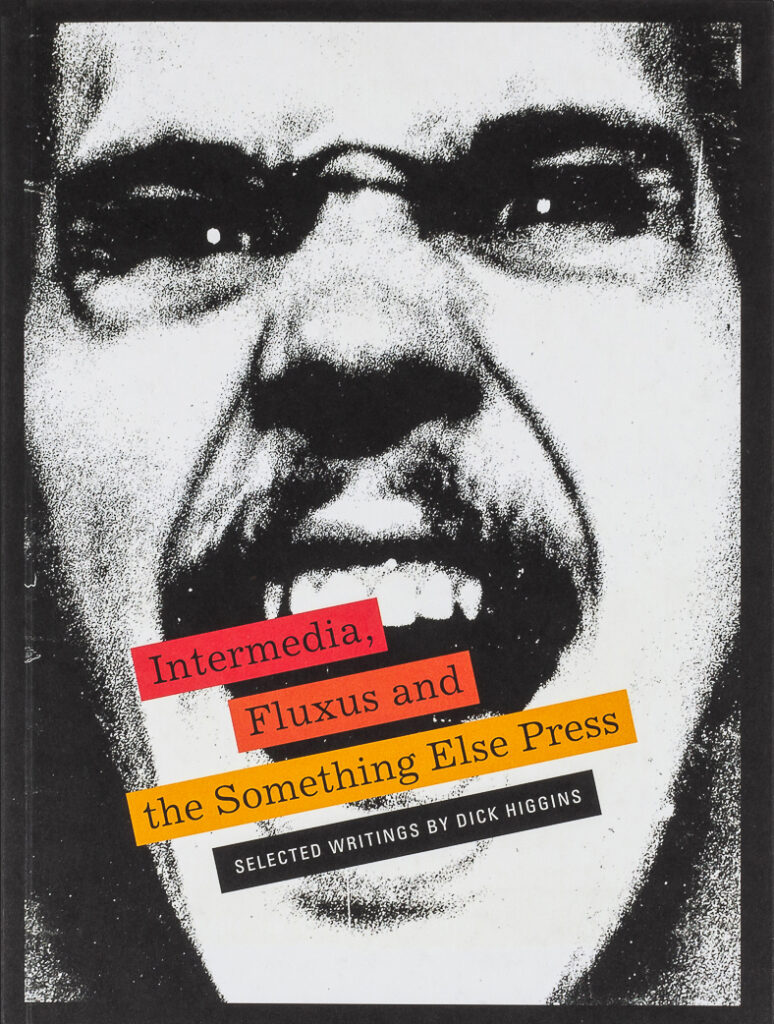

Yet, Fluxus historian Ken Friedman, in his introduction to Intermedia, Fluxus, and the Something Else Press, calls Higgins “a trade publisher”:8

He intended Something Else Press to be the smallest and most experimental of the big houses. […] Most Something Else Press books appeared in standard trade formats as clothbound editions suitable for libraries and scholars with a few paperback editions for students and artists. The Press distributed its books internationally through established firms rather than Fluxus-style committees. The Press published most editions in runs of three thousand to five thousand copies.

In reality, SEP’s business was not so booming. Though Higgins may have at moments believed in his own myth, sometimes exaggerating sales or print-runs, or may have wanted others to believe it—hence the business cards, the hardcovers, the first HQ in the Flatiron district with its “Great Bear” water cooler, and the population of the office with phantom employees like Camille Gordon—in reality, SEP functioned not unlike many “small, independent presses” of the time, and of our own.

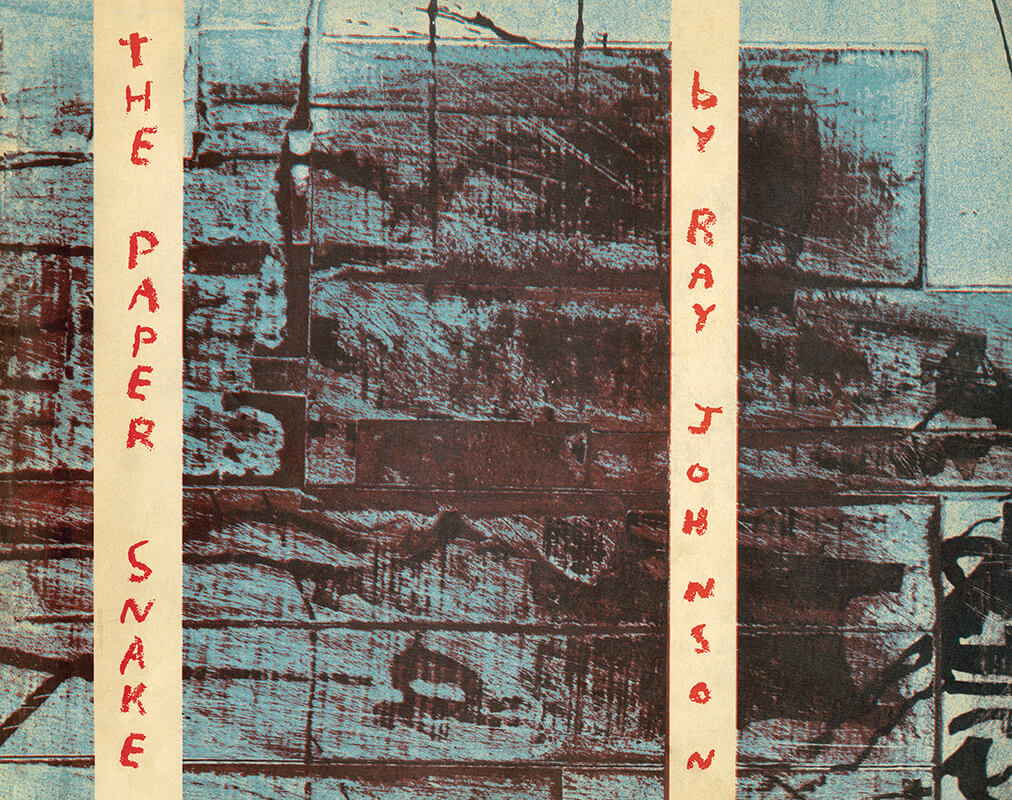

Very much aware of economies of scale and familiar with commercial printing, Higgins thought it more prudent to print about 1700 copies of Ray Johnson’s The Paper Snake (1965) because the “cost [was] very nearly the same as” doing 700.9 However, initial print runs were often lower than Friedman suggests: a few titles saw only 500 or 1000 copies in total. When SEP had a “hit” like An Anthology of Concrete Poetry,10 SEP’s cash flow, warehouse capacity, and distribution capability necessitated “short” runs of about 2000 to 4000 at a time, which meant the reprints were costly and brought little profit.11

Print runs depend on sales projections, but also distribution opportunities and fulfillment capability, and SEP’s main distributor was not the “established” commercial book distribution firm that Friedman imagines. The Book Organization, a charitable organization12 founded in 1968, was “a cooperative endeavor designed to strengthen book-store sales for a group of small art presses.”13 It never had more than twenty or so employees and sales reps throughout its life,14 so tales of a hundred salesmen going door to door around the nation with SEP books in their car boots are merely legend.15 In fact, SEP relied more on direct mail orders through their printed catalogs and a mailing list of five or six thousand names. Higgins fantasized about his books in supermarkets,16 and though the Berkeley Co-Op sold SEP’s Great Bear pamphlets in the vegetable aisle, he was not blind to the anomalous nature of this good will.17 And, as Friedman suggests, Higgins was ambitious about international reach (SEP catalog covers boasted headquarters in European cities alongside New York), though SEP seems to have been more successful at distributing foreign publishers’ books than achieving foreign distribution for its own.18

Not long after SEP left The Book Organization, Higgins devoted a whole Something Else Newsletter to the issue of distribution: “I had promised myself I wouldn’t write about business. But the corruption in my ‘industry’ is so total that I figured I’d better do so […] The book industry is the most stupid and the most corrupt of all in the country.”19 Here, Higgins exposes the issues plaguing the book industry from a small press position and laments how economics dictate that publishers “won’t publish serious literature.”20

A defining principle of small press is that its editors are frequently also publishers, designers, publicists, warehousers, and so forth.21 To wit, SEP never had more employees than you could “stuff in a taxi-cab”22—“If you need two cabs, you’re big business.”23—and all its staff “wore all the hats.”24 SEP was financially dependent on Higgins’ inherited money, until it ran out, but it also relied on grants from individuals and foundations: Higgins kept a list of “important cigars to light if money was needed.”25 Periodically, bank loans would pay the salaries and previous bank loans.26 One of SEP’s employees was never paid: Higgins himself.27 No proper trade “house” would have an unpaid “publisher.” Moreover, Higgins did most of the graphic layout and pre-press work and wrote a substantial part of the publicity copy and copious newsletters, all while serving as kind of artistic director, acquiring projects, and seeking financial support.

All told, Higgins’ missteps as a publisher were not outlandish—indeed, they were often the only steps available—and the financial troubles he faced due to tiny profit margins and other structural disadvantages of the economy of scale were common for both nonprofit small presses and for-profit independents.

In the early 1970s, after moving the press to his northern Vermont compound and hiring a new staff, Higgins took a break from SEP and started Unpublished Editions, which had “as its sole purpose the publication of fine limited editions of the otherwise unavailable works of Dick Higgins plus related materials.”28 Recalling the new venture in 1978, “in this way I got back into the small press world and away from the Something Else Press, which was such a sap on my energy.”29 Its first publication was amigo, a cycle of poems about his (mostly unrequited) lover Eugene, Emmett Williams’ son. Higgins had sensed that SEP wouldn’t do the book;30 his secretary and close friend Nelleke Rosenthal suggested he “do more Un-publishing.”31

By the mid 1970s, Unpublished Editions had become a cooperative32 with a number of friends publishing mostly their own work (Alison Knowles, John Cage, etc.), changing its name in 1978 to the ironically tautological Printed Editions. By this time, Higgins had already set up distribution through Truck Distributing (later Bookslinger) in St. Paul, a newly-formed purveyor geared toward literary small press books, which—Higgins lamented—had not existed at the time he ran SEP.33

The name of the new venture deserves further unpacking: “Editions” connotes the artistic practice of printing multiples, and stands in antinomy to “Press,” which, though also suggestive of the printing process and ownership of print technologies, had come to be identified with the organizational structure of the publishing house. Unpublished Editions signified a resolution between “my publishing and my creative work”—the small press offered him creative freedom with less financial strain. These editions were “unpublished” because they were “model editions of one’s less commercially viable work” which could “someday [be] reissued by commercial publishers.”34

With Higgins’ withdrawal of editorial oversight in the early 1970s, SEP had lost a cohesive strategy and a group of “members” to support, which soured his view of it. In fact, even at the time of Ray Johnson’s The Paper Snake—the first SEP book after Higgins’ own Jefferson’s Birthday/Postface—he foresaw that the venture would be short-lived, that he would someday “get sick and tired” of SEP, “you can bet your ass I will.”35

The break from SEP and the founding of Unpublished Editions took place at a time of personal trouble for Higgins: increased alcohol-dependency, a reassessment of sexual preference, an unsuccessful affair with a troubled young man, the end of his marriage, a nervous breakdown that led him to rehab. All this coincided with the IRS re-assessment of SEP as a hobby—something no trade press would be faced with—resulting in back-taxes on SEP’s and Higgins’ own business expenses, driving him to single-handedly dissolve SEP.36

The missing link in this trajectory, however, is that precisely from 1969 to the end of SEP’s life Higgins was involved with the grass-roots small press organization, COSMEP (Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publishers). No critical text on SEP’s activities mentions this strange acronym—a lacuna that manifests the prevailing disregard of the small press context in studies of post-war avant-garde arts. Yet, Higgins’ association with COSMEP—and by extension with a world of small press publishers—from at least 1969 onward (half of the life of SEP) affected his conceptualization of publishing more so than his association with Fluxus and FluxFriends.

The explosion of small press activity during the “mimeo revolution” of the 1960s—the emergence of a great quantity of marginal publishers and little magazines—is generally regarded as a heyday of U.S. literary counter-culture. Celebrating this period, Jerome Rothenberg writes that “the part by which [American poetry] has & will be known” is “the creation of those poets who have seized or often have invented their own means of production and of distribution.”37 The value of the small press has long been centered in its marginality in relation to commercial culture and, more precisely, in what poet/scholar Michael Davidson has called its revival of aura through the utilization of “cheap, portable print technologies to render ‘authentic’ gesture.”38 Material conditions—amateur printing, often utilizing inexpensive or DIY printing methods like mimeo, hand-collation, and stapling aided by peers and friends of the publisher in communal fashion, fast-paced output, and small print runs—served to both define the look of mimeo-revolution publications and announce their outsider politics. These material and technological factors were as important as content in signifying “an expressive poetics that validated personal gestures of discovery and speculation over artisanal values of order and control.”39

To find connections between poetry, small press publishing, and the art scene of the early 1960s, one may look no further than Higgins’ own network. His earliest publication in The Beat Scene coincides with the beginning of his downtown New York coffee shop performances (with Al Hansen as New York Audio-Visual Group) and involvement in the earliest Happenings. Similarly, Higgins’ creation of the Ray Gun Spex series at Judson Church (with Kaprow, Dine, Oldenberg, Hansen, etc.) was contemporaneous with fellow 1958-Cage-class attendee Jackson Mac Low’s collation (with LaMonte Young) of performance notations for Beatitude East—a special issue of Beat-associated poet and City Lights author Bob Kaufman’s poetry magazine Beatitude—which included Higgins among its contributors.40

Toward the end of that decade of ramped up small press activity, in direct response to the proliferation of small literary periodicals and presses, a number of editors and publishers organized in 1968 to form COSMEP. It arose almost simultaneously with similar organizations in the States (CCLM, NESPA, WIND; Midwest, UPS, etc.) and in other countries (ALP in the UK, COPLAI in Argentina).41 Together with new journals (Tom Montag’s Margins, Len Fulton’s Small Press Review, etc.) that served small press communities by reviewing their books and publicizing their issues, these fledgling organizations heralded a new era of small press as a conscious and united (though disparate) movement. Envisioned as a kind of union (“for we are workers”42) or guild (“for we are craftsmen”43), COSMEP focused on the thorough indexing of, and networking between, little magazines and small presses, as well as advocacy on their behalf for better media coverage, and the education of librarians and broader publics on their publications. By 1978, it had 1200 members and had convened ten annual conferences, at least two of which Higgins had attended. “[COSMEP] sponsored library and prison projects, published a series of booklets to help new publishers and published a newsletter that allowed for lively discussion of issues facing publishers.”44

The small presses united in COSMEP did not see themselves as the “smallest of the big houses,” but as viable alternatives. Among their membership were presses calling themselves “independent” (e.g. Toothpaste Press, which later became Coffee House Press), as well as literary small presses and little magazines (but not the big university reviews) of all stripes, including those that COSMEP sometimes referred to as “minority” or “special interest” publishers—Native American, Feminist, LGBT, Latino, and Black presses and magazines. Also included were outfits specifically devoted to prison literature, a handful of hippie tabloids, leftist presses, purveyors of psychedelic literature, back-to-the-land resource publications—in short, all manner of counter-cultural identities and positions were united under the small press umbrella.

Simultaneously, funding sources were emerging: state arts councils began opening up their doors to publishers, and the new NEA partnered with CCLM (the Coordinating Council of Little Magazines45) to eventually dole out “$3.4 million to more than 1500 different magazines” between 1967 and 1984.46 The NEA also funded individual writers and some small press book publishers.47 By the time SEP closed shop, Higgins was very much aware (as were all COSMEP members) of controversies surrounding CCLM’s position as distributor of NEA-granted funds.48

Distribution was also frequently discussed in COSMEP newsletters and related publications. Beginning in the late 1960s and early ’70s, the needs of small presses began to be met by a variety of emerging alternative structures specializing in trafficking small press publications.49 The arrival of small press distributors preceded and coincided with the founding of artist-run bookshop/galleries with a mission to make the emerging field of artists books available to the public.50 By the mid-’70s, Higgins was writing to COSMEP leadership about the inclusion of artists book publishers in their membership.

One of COSMEP’s founding members and a member of its Board of Directors, Hugh Fox (editor of Ghost Dance Press), had been working as far back as 1966 with Higgins on The Collected Poems of “the American avant-garde poet writer” Abraham Lincoln Gillespie, envisioned for SEP, but not brought to press.51 It was perhaps through this association that Higgins was invited to get involved with the organization. In June 1969, he attended the COSMEP conference in Ann Arbor, where he also participated in a reading. The resulting COSMEP Anthology featured poems by Higgins, who in his bio called SEP “the largest publisher of way out ‘freak’ lit in the U.S.,” and referred to himself not as an artist but as “playwright, poet, cinematographer and creator of ‘happenings’.”52

It’s no surprise that Higgins would have been a desirable collaborator for COSMEP—his deep knowledge of book manufacture and design and the quality and reach of SEP productions were well known—and he reciprocated. He served one term on the COSMEP board (1972-73) where, in his own words, his goals were to “a) increase business and production sophistocation [sic] among members, b) do a WHOLE COSMEP CATALOG to help publicize members’ identities, and c) encourage greater membership participation among women. My projects were accomplished, so I served out my turn but did not run again.”53

According to independent publisher Harry Smith, when the COSMEP board became aware of the fact that “women were excluded from printing colleges, […] Higgins led a printing workshop” for female members of COSMEP at its 1973 conference, “beginning at a large full-service printing company and culminating in the paste-up of The Whole COSMEP Catalog, which became a small press bestseller.”54 Higgins was the Catalog’s production manager, liaising with the 100 publishers to be included, and saw to the pre-press photography. He was nominated to serve on the board again in early 1974, but declined due to a time of personal troubles and his worries over SEP’s finances: “this isn’t the year for me,” he typed in all lowercase to COSMEP’s sole administrator, Richard Morris, “i’d like to serve again in ’76-’77 if called on to do so, because i like us and would like to pitch in and get some more things done. there’s always plenty of problems.”55

The January 1974 COSMEP Newsletter reported that “Dick Higgins has left Something Else Press, which is now being run by Jan Herman and George Mattingly.”56 The same issue announced that the Whole COSMEP Catalog was finally at the printers; it had missed its pub date of late 1973. Despite his own troubles, in early 1975, just weeks after filing bankruptcy for SEP, Higgins wrote to Morris with candid concerns about the direction of COSMEP: “I am really most worried about the divisiveness (feminists vs. everybody else, regionalists vs. COSMEP57), the emphasis on grants, and the lack of concrete projects for increasing information flow to members and to the public. The momentum of a few years ago seems to have been lost.” He confided that he was “not impressed by the present board” and recommended “more activism, less decentralization, and more sophistocation [sic] in general.”58

Through his experience as a publisher and his involvement with COSMEP, Higgins grew increasingly critical of the mainstream “pudgies”—as he called them—of commercial publishing. Imagining the fate of a book like John Cage’s Notations (SEP, 1969) in the hands of the “organizational system” that could financially support such a project, he concludes that “a conservative editor would have intervened—would have said: ‘The salesmen won’t like that.’”59 Higgins came to think, echoing others in the independent publishing community,60 that outfits like SEP and Printed Editions should be supported by the trade publishers to do “research and development” for the industry. “We,” Higgins wrote, meaning smaller publishers, “can provide them with paradigms and models to imitate.”61

Higgins’ unilateral move to close SEP was a financial necessity, but it was also no longer the small press he had built and which he desired. His reassessment of priorities was a product of his deepening involvement with small press publishers and his coalition-building work within that community. He summarized the publishing approach of Printed Editions as “research and development,” taking care, once again, to position it as “something else”: “publishing with trade publishers is for after the audience for an artist has been built. Groups like ours are for before that has happened, and for situations (like Cage’s) where the particular project is simply not salable on a large basis.”62 Interestingly, Higgins’ life as a publisher ended when this publishing co-op closed in 1986, because “so many other publishers wanted to produce our main titles that we had no major books for Printed Editions. So we agreed to disband. Mission accomplished.”63

On the whole, the myth around SEP’s status and supposed “success” as an unusual trade press has served to drive deeper a wedge that obfuscates SEP’s relationship with the contemporaneous small press movement. Moreover, the incorporation of SEP’s publications into the history of art (and the artists book in particular) has contributed to a simplification of the context of its activity and has overshadowed any consideration of the history of its evolution in relation to the growth of small press networks.

Higgins worked in a milieu of small press publishers and independents at a time of optimism about the possibilities of autonomous systems of the attribution of aesthetic value, non-commercial and cooperative models for art-making (as exemplified by the artists book as institutional critique of commercial galleries and museums), and alternative forms of literary circulation pioneered by the poet-publishers of the mimeo revolution. A reassessment of SEP’s history through the lens of Higgins’ involvement with COSMEP brings with it the possibility of understanding SEP’s position within, rather than extraneous to—or exceptionally outside of—the small press ecology and the politics inherent to its self-consciousness as a movement.

Matvei Yankelevich is a translator, poet, and a founding member of the Ugly Duckling Presse editorial collective. He is the editor in chief of World Poetry Books and the founder and publisher of Winter Editions. He teaches courses on translation, publishing, and print culture at Columbia University’s School of the Arts. His four-part series of essays on small press histories, beginning with “’Power to the people’s mimeo machines!’ or the Politicization of Small Press Aesthetics,” appeared on Harriet in February 2020.

The author thanks Alice Centamore at the Emily Harvey Foundation for her for assistance with Dick Higgins’ COSMEP-related correspondence.

endnotes

1 Much has been written about the artists books “movement” and the small press “revolution,” but often only separately, in studies that are tethered to their respective frameworks—departments of Art History and of English. Mentions of 0 to 9 and Fuck You: A Magazine of the Arts in studies from both literary and art angles are some of the few outliers that prove the rule, as are bipartisan nods to the Something Else Press.

2 Higgins thought of himself as both writer and artist, and more—”I have chosen all the arts as my media or intermedia.” Intermedia, Fluxus, and the Something Else Press: Selected Writings by Dick Higgins (eds. Steve Clay and Ken Friedman), Siglio, 2018, 268.

3 According to Higgins, SEP published “the sort of avant-garde work which offers a real alternative to the conventional art forms and which normal publishers do not know how to handle.” (IFSEP, 128.) [My emphasis.]

4 IFSEP, 142.

5 IFSEP, 143.

6 IFSEP, 169.

7 “Two Sides of a Coin: Fluxus and the Something Else Press,” originally published in Visible Language 26, no. 1/2, (1992). (IFSEP, 141.) [My emphasis.]

8 IFSEP, 18.

9 From a letter to Ray Johnson (IFSEP, 174). The final tally, according to the “Checklist” in IFSEP, was 1840 copies, 197 of which were sold as a special edition that included “an original collage, or ephemera by Johnson” (IFSEP, 177).

10 Higgins claimed that there were 17,000 or 18,000 printed overall, though, according to Steven Clay’s recent checklist, it was likely around 12,000. (IFSEP, 185.)

11 Whatever the print runs, much of SEP’s stock had to be given away to libraries or remaindered after Higgins filed for the company’s bankruptcy in December, 1974. He was relieved that the books weren’t pulped. (IFSEP, 167.)

12 IFSEP, 162. Higgins gripes about The Book Organization’s use of public funding in Something Else Newsletter 2, no. 7 (1973): 3.

13 Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Photography. Lynne Warren, ed. (Routledge, 2005). Diane Kruchow, reporting for Margins in 1974, notes that people “from Aperture, Corinth Books, Croton Press, Eakins Press, Glide Publications, The Jargon Society, Big Rock Candy Mountain and Something Else Press decided to pool their resources and form a corporation to distribute their publications.” (“Eastern & Southern United States,” Margins 11 [April-May 1974]: 14.) The director was Michael Hoffman, editor at Aperture. Some sources suggest that Hoffman and Jargon Society editor Jonathan Williams, were the key founders.

14 By 1974, with eight to ten employees, it was representing a total of only nine presses, mostly focusing on Aperture books and Aperture magazine, with thirteen salesmen in the U.S.; it had started with ten in the U.S. and four abroad. (See Warren, ibid.)

15 In the late 1960s, SEP “had one lone but quite enterprising commission salesman—Russell Chaskin.” (IFSEP, 156.)

16 Similar sentiments were popular with proponents of the artists book in the later 1970s, e.g., Lucy Lippard, “The Artist’s Book Goes Public,” Artists’ Books: A Critical Anthology and Sourcebook (ed. Joan Lyons), Visual Studies Workshop, 1985, 48; originally published in Art in America 65, no. 1 (1977).

17 IFSEP, 147, 153.

18 In 1969, Higgins called SEP “a distribution focal point for European latest trends.” (Higgins’ biographical statement, Anthology 2, COSMEP, 1969, 27).

19 SEP Newsletter 2, no. 7 (1973): 1.

20 Ibid., 2.

21 See my essay, “’Fervent and Utopian’: Small Press at a Crossroads,” Harriet, February 25, 2020, in the section titled “’Small Press is…?’ Editor-Run Publishing, Economics, and Volunteerism.”

22 IFSEP, 141.

23 Something Else Newsletter 2, no. 7 (1973): 3.

24 IFSEP, 169. See also “What to Look for in a Book—Physically,” 1965: “We try to offset [costs] as much as we can by doing as much of the work ourselves as we can—all the camera work on our new titles, for example…” (IFSEP, 128.)

25 IFSEP, 165.

26 Higgins set up a “parallel foundation to the Press, and it could be used to get money for productions, but overhead was always hard to finance.” (IFSEP, 161)

27 ibid.; see also IFSEP, 168: “I never made a penny on that Press.”

28 Unpublished Editions letterhead, sidebar text, circa 1974. The “un” in “Unpublished Editions” is set off in red roman capitals from the italic blue text, both in header and sidebar.

29 IFSEP, 163.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid.

32 See “Notes for a History to be Written Some Day,” IFSEP, 170-71; e.g. “And where is the organization? There isn’t any. […] There is no waste, no administrative cost. […] there is flexibility in smallness. I think the future of publishing will include many small groups like ours. “Trade publishing […] has the key role. We cannot replace it.”

33 “They are one of several organizations specializing in the problems of small press distribution. At the time I did Something Else Press, there were, as such, no such organizations. Hoffman’s group was almost a prototype, but it assumed huge production plans and required gargantuan budgets to function at all. Truck assumes only editorial quality, sells hard, and carries on in a businesslike way, but is small and prefers to keep it that way, good for pocket publishing and not just mega-publishing.” (IFSEP, 170.)

34 “The Strategy of Each of my Books,” IFSEP, 262.

35 Letter to Ray Johnson, IFSEP, 174.

36 “Incidentally, when the Press finally went bankrupt, it owed well over $325,000.” (IFSEP, 165.) Higgins writes of his lack of confidence in his last hired editor in “Notes for a History to be Written Some Day” (IFSEP, 165-66) and “Two Sides of a Coin: Fluxus and the Something Else Press” (IFSEP, 141).

37 “Pre-Face,” A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980, (eds. Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips), New York Public Library / Granary Books, 1998, 9.

38 Michael Davidson, Ghostlier Demarcations: Modern Poetry and the Material Word, University of California Press, 1997, 31.

39 Ibid.

40 Though the work on this issue began in 1961, the magazine folded before the issue could be published, but it soon appeared as An Anthology of Chance Operations (1963), designed by George Maciunas and self-published by Mac Low and Young.

41 “The past decade—the past half decade particularly—has seen the small presses collect.” Len Fulton, “Org, Egg, and Archetype,” Small Press Review 12, (1972), cover verso. CCLM = Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines, NESPA = New England Small Press Association, UPS = The Underground Press Syndicate, ALP = The Association of Little Presses, COPLAI = Confedaración de Publicaciones Literarias Independientes. Other names are not acronyms.

42 Ibid., 2.

43 Ibid.

44 Tom Person, “Life After COSMEP.” Small Press, 1996.

45 In 1990, CCLM changed its name to CLMP, Council of Literary Magazines and Presses.

46 Pauline Uchmanowicz, “A Brief History of CCLM/CLMP,” The Massachusetts Review. 44:1/2 (2003): 82.

47 For more on CCLM’s history, see my essay “Autonomy’s Compromise and the Professionalization of the Small Press,” Harriet, February 10, 2020.

48 See especially the lively discussion of CCLM and the NEA in the “Grants” section of Margins 14, (1974), which includes mention of Higgins, in an article by Richard Kostelanetz, as one of the few experimental writers to receive a “publicly funded” grant: “Of the scores of literary professionals supported by Poets & Writers, Inc., during 1972-3 (according to the annual report of the NY State Council on the Arts), only one does visual poetry (Mary Ellen Solt), only one is involved with alternative poetic; syntax (Dick Higgins), and none do sound poetry.”

49 These included Serendipity Books Distribution (1969) in the Bay Area, a precursor to SPD (Small Press Distribution); the short-lived WIND; Midwest; as well as Truck (the earlier form of Bookslinger) in St. Paul. Of these, SPD would have been an ideal distributor for SEP had the Press lasted a few more years, especially if it had gone on to publish poets the likes of Bernadette Mayer and Clark Coolidge as its last editor, Jan Herman, had planned.

50 Art Metropole, Toronto; Other Books & So, Amsterdam; Coracle Press, London (all 1975); and Printed Matter, NYC (1976).

51 Higgins had gone so far as to write jacket copy for the book. See IFSEP, 229.

52 Anthology 2: of poems read at the Midwest COSMEP conference held at Ann Arbor, June 1969 (ed. Hugh Fox), 27.

53 Typewritten petition of self-nomination to the COSMEP board, addressed to “Fellow members,” February [1976?]. The Getty Archives.

54 Prairie Schooner 78, no. 4 (2004): 49.

55 Letter to Richard Morris, COSMEP Coordinator, April 8, 1974. The Getty Archives.

56 COSMEP Newsletter, 5:4. Why George Mattingly is mentioned is unclear. Higgins makes no mention of him in his writings on the history of SEP, though he did know Mattingly well enough. He is listed along with Higgins as one of the editors of the Whole COSMEP Catalog. Higgins thought of him as a good Board prospect for COSMEP (see letter to Mattingly, Harry Smith, and Len Fulton from January 2, 1975, Getty Archives). Some of Mattingly’s papers are housed in the Jan Herman archive at Northwestern.

57 There had been talk in the COSMEP membership about breaking out into COSMEP West, East, and Midwest, to concentrate on regional issues.

58 Letter to Richard Morris, COSMEP Coordinator, January 2, 1975. The Getty Archives.

59 IFSEP, 169.

60 cf. Bill Henderson’s on the economic good sense for commercial houses to “back a principal source of their wealth: the talent nurtured and the books produced in the small presses.” (“Independent Publishing: Today and Yesterday.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 421, [1975].)

61 IFSEP, 171.

62 IFSEP, 171.

63 IFSEP, 142.

see also

Affinities

Dick Higgins’s Something Else Press Lives On...Its extraordinary list still makes many independent publishers swoon

Affinities

“Higginsonian Pleasure All Around”Joshua Beckman

Books

Intermedia, Fluxus and The Something Else Press: Selected WritingsEdited by Steve Clay and Ken Friedman

Books

Paper Snake

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

May 27, 2024—Eggs, books, etc.: The first book in siglio’s new habitat is just about laid. Our local snapping turtle George perambulated the house in driving rain, determined and curious, then laid her eggs at our doorstep. Do snapping turtles and publishers share common traits? Oh, so very, very slow. Reportedly testy but actually timid. A group of them might be a bale, nest, turn, dole, or creep—though ours seems solitary. Only 10% of her eggs will survive as hatchlings. Make of it what you will. Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers goes on press very soon. One sleeper said to Calle: “I’ve often dreamt of an egg that was enormous ovoid transgression. The original sin of Adam & Eve is a hard-boiled egg.” Meanwhile, many sightings of goslings, kits, poults, and one fawn too: how easily the others propagate, alas.

[...]