Suspended PleasuresInside Bernadette Mayer's Time CapsuleDan Chiasson, The New Yorker

reviews, 09/07/20

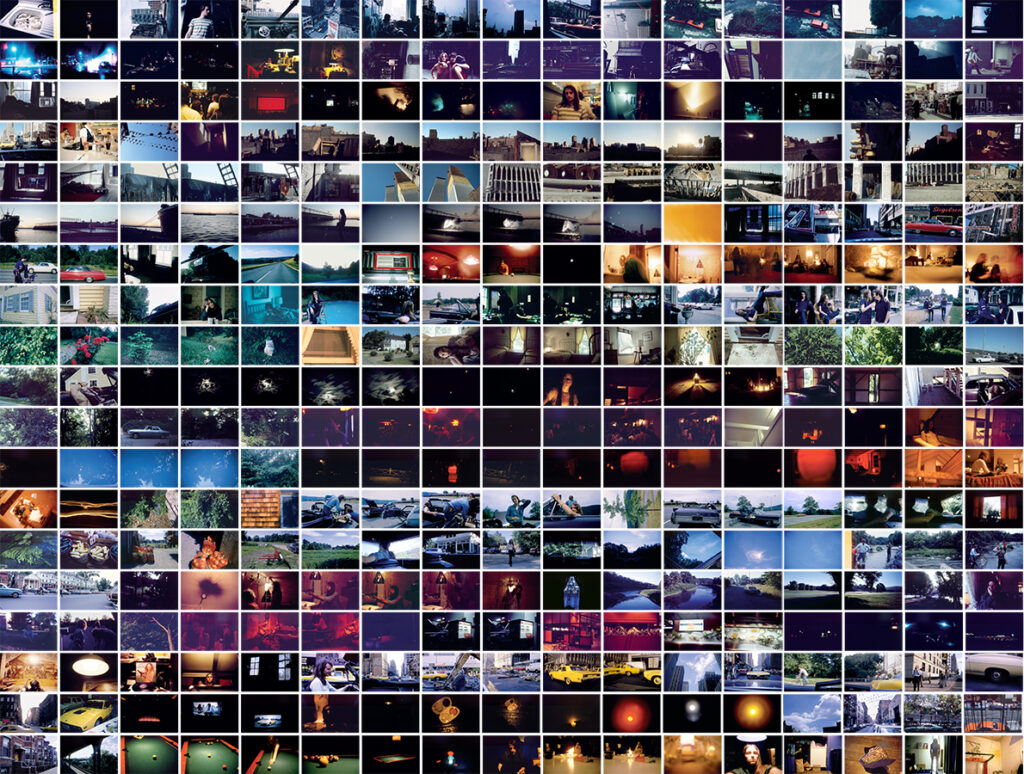

In July, 1971, Mayer shot a roll of film every day, documenting her journeys between New York City and the Berkshires.Courtesy Bernadette Mayer Papers, Special Collections & Archives, University of California, San Diego

On July 1, 1971, the American poet and conceptual artist Bernadette Mayer began to record one month of her life by shooting a roll of thirty-six color snapshots every day, developing them at night, and keeping a diary of her impressions. The resulting amalgam, a “crazy headed journal” that she called “Memory,” was shown as a mixed-media installation at a SoHo gallery in 1972: a honeycomb of more than a thousand three-by-five photographs mounted to the gallery walls, with six hours of narration playing on a loop. Whatever memory is, “Memory” was an exploration of the layers of what a person thinks they remember firsthand.

The project follows a band of New Yorkers, led by Mayer and her boyfriend at the time, the filmmaker Ed Bowes, back and forth between the city and Massachusetts, where Bowes had a gig shooting films for the Berkshire Theatre Festival. The exhibition of “Memory” operated almost as a film: viewers provided the motion as they followed the cell-like stills across the walls; the extremely committed could even pace themselves in order to synch the audio to the images. These mini temporal dramas eddy within the larger experience of passing time. From July 14th, Mayer gives us five shots of a game of bar pool, beginning with the break and ending when the last ball is sunk.

This spirit of transience extended to “Memory” itself, which for decades lived mainly in memory, surfacing every now and then in altered forms. In 1975, an edited version of Mayer’s script and a handful of photographs were published as a book. In 2016 and 2017, the whole experience was restaged in Chicago and in New York City. This year, the project has morphed yet again: all the photographs, along with Mayer’s original diary, have been published by Siglio, a new and beautiful embodiment of the work that speaks uncannily to our particular time.

Nostalgia—for the carnal, improvised mood of 1971, but also for the halcyon days of, say, last summer, before we were afraid of communal life—has become the work’s dominant key. Yet “Memory” also seems ahead of its time: a database of half-captured meals, barns, bodies—a kind of analog Internet. The visual images are underexposed, overexposed, and double-exposed. Objects are edged half into or half out of the frame; scenes are never complete. The text propels you past tantalizing sights and experiences. It’s all too much, in ways that seem very familiar to anyone who watches stimuli whiz by in a feed.

“Memory” was always a definitional project; that’s why it’s not called “Memories.” But its proposal for how memory works changes each time the work changes form. Bound in a book, “Memory” is set free within time and space. The Airstreams and roadsters, the delis and coffees are there whenever and wherever we want to experience them, and they can be reanimated on demand. Reading “Memory” with a phone handy, I followed Mayer and her crew along the back roads of the Berkshires to Nejaime’s, a local liquor store, which, I learned, stayed open this spring, deemed an essential business. In the city, Mayer took a photograph of a New York storefront: Casa Moneo. The business closed in 1988, but Google reveals its old address, on Fourteenth Street, in a building that once housed Marcel Duchamp’s studio. When I came across mysteries in the text—a forgotten restaurant, a long-gone landmark—I posed my questions to the Internet, and got answers from the hive mind. Though “Memory” is a famous work, it has been experienced firsthand by relatively few people: it is still a choose-your-own-adventure—uncharted, wide open. Finding a path through “Memory” seems like both a highly personal lark and a spur to collaborate.

William James once distinguished between “substantive” and “transitive” states of mind: the difference between “a feeling of blue or a feeling of cold” and “a feeling of if, a feeling of but, a feeling of by.” “Memory” tempts you to linger on the substantive, but, with its bountiful cars, highways, gas stations, rivers, and bridges, it’s really about getting somewhere. It is happiest in the in-between, and hyperalert to its own transit from one word and image to the next. There are many road trips’ worth of words—often erratically, racing to catch up with memories before their vividness fades. Syntax is stripped down, simple nouns sutured together with ampersands and commas. A conventional English sentence works by subordinating some elements while elevating others. But here, as on a highway, language passes at a steady, constant clip: “71 degrees ed’s reading in the back of the car & a truck with a turquoise thing a trailer back in it crosses the road, iroquois, two people in a sports car a neat compact close fast moving unit.” A tragic detail, the word “iroquois,” zips by on the side of a truck. That’s America.

It’s hard to quote from “Memory,” since its dense linguistic braid unravels when you sever it. The text often tries, almost comically, to guide itself along its own infinitely branching paths. There are detailed driving directions, swimming holes you can still find on a map, step-by-step recipes, and an ad for a steak-delivery place with a once dialable phone number. (I found the place—at 58 Greenwich Avenue—mentioned in an old newspaper online.) As “Memory” approaches its conclusion, it becomes more aware of the date on the calendar, more consumed with itself—a transcript of a transcript. “& as I write all this stuff down I know it comes out of nowhere goes nowhere & remains, nothing leaves,” Mayer writes. “E back tom. That’s short 4 tomorrow this kind of writing makes it impossible to think straight.”

Mayer wanted “Memory” to serve as a time capsule, its meaning deferred until a future, or a range of futures, that she couldn’t have foreseen. She later said she’d “chosen this month in the forsythia-falling-from-branches seventies at random.” The images she conjures and captures are a kind of timeless Arcady, where capering young lovers address temporality as a series of daily jaunts. Elegy always has a way of creeping into art that documents the once teeming, now empty past: it is almost too painful to glimpse the innocence and the freedom of Mayer’s summer from the point of view of our current fearful season. It can seem a dubious advantage to have survived all those disconnected phones, defunct addresses, dead or forgotten friends. At our moment in history, “Memory” reads in part as an archive of suspended (in both senses of the word) pleasures. “Old cemetery we looked for a place to swim,” Mayer writes. “I showed grace the insane gazebo with wooden horse & carriage.” These pleasures are privileges, too. Mayer and her friends are white: no Black American would feel as free trespassing in somebody’s woods—not then, and not now.

History cannot be banished from the garden. Mayer’s entry from July 4th takes her to the World Trade Center, then under construction. In the early phases of assembling her own ambitious edifice, she marvels at all the rusted steel and rubble around the site. It’s part of a dynamic, jackhammering New York, where destruction and progress sit side by side. To read this day’s entry is to remember the look of those buildings as they came down. A piece of prophecy is accidentally found among the shards of memory. “When I’m not driving I’m thinking,” Mayer writes. “Some memories qualify where the present endures not for a minute or an hour or a day but for weeks & months & years.” The World Trade Center is a memory, but “Memory” is itself still being constructed, reader by reader. You never know when the present instant will end; sometimes it lasts thirty years.

“Suspended Pleasures,” review by Dan Chiasson, The New Yorker. Originally published in the September 7, 2020 issue. Read the review online at The New Yorker.

see also

✼ the improbable:

from Issue, No. 1 (Time Indefinite), “Dick Higgins, Publisher: Notes Toward a Reassessment of the Something Else Press Within a Small Press History” by Matvei Yankelevich: “To find connections between poetry, small press publishing, and the art scene of the early 1960s, one may look no further than Higgins’ own network.”

[...]