A Forest of Non SequitorsElisabeth Kley, Artnews

reviews, 05/01/13

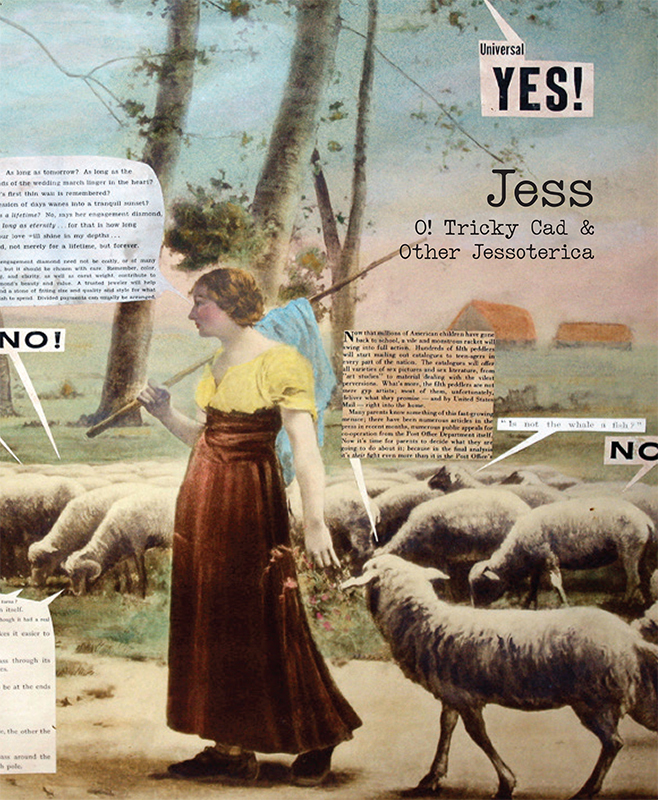

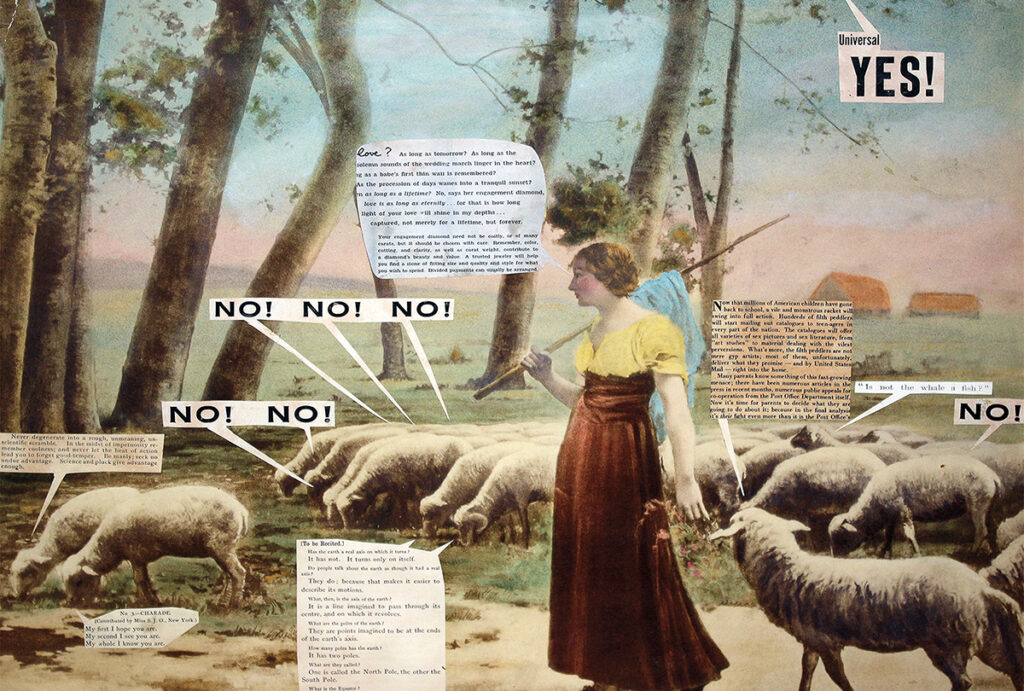

Perhaps due to the fact that all of its illustrated collages were originally constructed from printed material, Jess: O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica is a sumptuous publication that comes close to palpably duplicating the art it reproduces. Trained as a chemist—and thus an expert in unexpected combinations—Burgess Collins (1923–2004), later known simply as Jess, helped produce plutonium for the Manhattan Project when he was in the army during World War II. After nightmares about future atomic destruction convinced him to abandon science, he enrolled in art school in California in 1949. Two years later, he met poet Robert Duncan. They lived together in San Francisco until Duncan died in 1988.

Jess’s intricate collages were primarily inspired by Max Ernst’s 1934 Une semaine de bonté, a picture-book series containing saccharine Victorian illustrations reassembled into menacing Surrealist tableaux, and by James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, with its illogical language invented out of portions of common words.

A detail of “Nance,” 1956 in Jess: O! Tricky Cad & Other Jessoterica.

Jess begins with several examples of Tricky Cad (1954–59), reconfigurations of Dick Tracy comics with dialogue and images scrambled into slapstick successions of bewildering non sequiturs. In one of these, a pair of detectives in trench coats gets lost in a snowy forest. “Hey! I hear the roar in the blizzard,” says one. “Hey! Tell the tree!” the other replies.

Enchantingly placed inside a glued-in paper pocket is a complete reproduction of Jess’s pamphlet O! (1960). On the cover, a picture of W.C. Fields with his eyes closed exudes a thought bubble announcing, “Fancy—Imagination!” Inside, multitudes of incongruous images come together, including a tiny armored knight thrusting his sword below a monumental winged nymph, exhorting the reader to “feel what I have felt.” With references to alchemy and mythology, such collages recall similar works by Joseph Cornell.

The book also contains a series of poem collages created between 1952 and ’59. These bits of text, assembled into evocative combinations, predate the “cutups” used by William S. Burroughs to write his 1961 novel The Soft Machine. Jess christened his method “paste-up,” drawing attention to its kinship with graphic design while suggesting that creation is born out of fragmentation.

Anticipating Charles Henri Ford’s poem posters and Ray Johnson’s whimsical mail art, Jess inaugurated a universe of ceaselessly fluctuating, erudite wordplay and poetic transformation.

Originally published May 2013.

see also

✼ elsewhere:

“In my opinion, genre is a way of speaking about conventions of reading and looking, where you sit or stand and whether you’re allowed to talk to other people or move around while you’re communing with an object or text.” —Lucy Ives, from her interview with Karla Kelsey in Feminist Poetics of the Archive at Tupelo Quarterly

[...]