Afterword to A Picture Is Always a BookFurther Writing from Book of Ruth by Robert SeydelLisa Pearson

excerpts, 08/07/14

Published in A Picture Is Always a Book: Further Writings from Book of Ruth by Robert Seydel, edited by Lisa Pearson, Siglio, 2014. All rights reserved. © 2014 Lisa Pearson and Siglio Press.

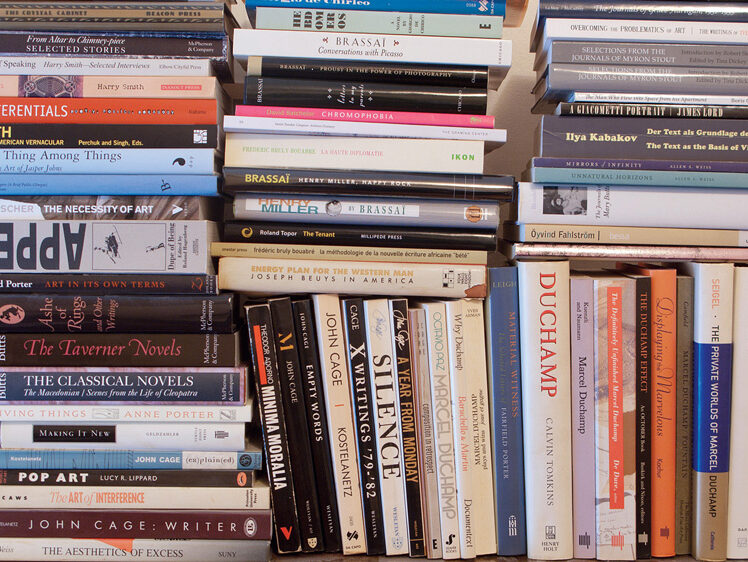

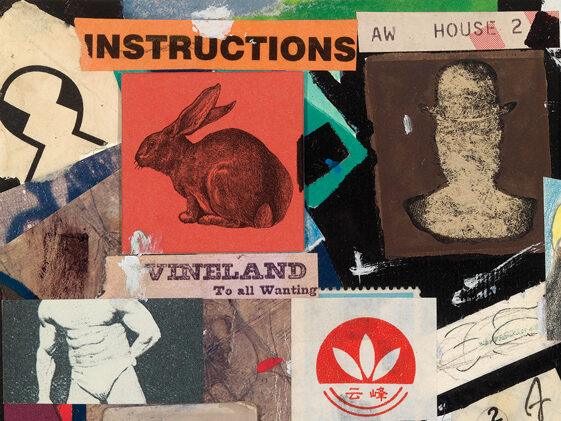

A Picture Is Always a Book: Further Writings from Book of Ruth includes virtually all of the works Robert Seydel called the “journal pages,” writings authored by his alter ego Ruth Greisman, typed on brittle sheets of paper purloined from old photo albums and drawn on with colored pencils, oil pens, white-out and ink stamps.1 They belong to a body of work with permeable borders2 that Seydel created under the guise of Ruth who was inspired by Seydel’s own aunt of the same name who also lived in Queens with her brother Sol:

“Sol (sometimes Saul) was in real life a veteran of the First World War and suffered, as it was later said, from shell shock. After the war he became a plumber. Ruth was a Sunday painter who worked days in a bank and was active in Hadassah … The two of them meet [Joseph] Cornell and, through him, Marcel Duchamp. Ruth fell in love with the former who was, in his own way, as impossible and sealed-off as her brother. … Her work was first discovered among the boxes of miscellanea in the Joseph Cornell Study Center at the Archives for American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Later research by family members turned up a treasure trove of material in a garage in suburban Fort Lee, New Jersey.”3

Though this Ruth is a fictional creation (“pretty much a complete fabrication” Seydel says in the interview that follows), some of Seydel’s family history percolates to the surface, and his own personal circumstances (his travels to New Mexico, for example) color Ruth’s experiences. She is on one hand, as Seydel says, “a kind of exit out of the self” and yet on the other, there is no way to fully separate Robert Seydel and Ruth Greisman. His hand is hers, her voice his own—albeit in a different register with a particular diction, proclivities and desires: “Things twist up with her, I’m more entangled in her possibilities and dilemmas, I have a harder time distinguishing between us.”

This selection of “further writings” includes all but a very small handful of the journal pages (I mostly left out those that were earlier versions, sometimes literally “cancelled” with a “x” drawn on them). There are other “writings,” notably the set of aphorisms “Formulas & Flowers” which was published in Book of Ruth (Siglio, 2011) as well as unrevised writings attributed to Ruth throughout Seydel’s notebooks, selections from which are included in the exhibition “Robert Seydel: The Eye in Matter” that A Picture Is Always a Book accompanies. Many of Ruth’s journal pages began as hand-written pieces on the pages of Seydel’s Moleskine notebooks (or “Knotbooks,” as he referred to them), often painstakingly revised and remade into the objects reproduced here. Yet, as with all of Seydel’s work, nothing fits tidily into any category: the “writings” permeate everything; language is everywhere; all things are meant to be read.

The sequence of these works likely does not remotely resemble the sequence Seydel himself would have assembled. He spent more than a year selecting and revising over and over again the sequence of collages, drawings and journal pages for the Siglio publication Book of Ruth. In the appendix of that book where the majority of the journal pages appear, they move one to the next using nodes of both convergence and divergence, some identifiable on the surface as textual or visual detail, others buried as internal references, perhaps linking to or brushing up against an idea or line from another author or artist, or even sometimes simply through Seydel’s way of seeing a particular page, the way he might have categorized it, unbeknownst to the reader.

In putting together this sequence for A Picture Is Always a Book, I’ve kept in mind Seydel’s wariness of linear movement, of narrative device, and of the allegorical assignments that constrain rather than expand meaning, but I’ve also been keenly aware of the kinds of contradictions Seydel lived within—the work as a means to get beyond the self and yet as also inextricable from self; the thin conceit of the persona as carrying the complex weight of the character; the merging of the real and the imagined; and the narrative inherent in this body of work by virtue of the accumulations, the emotional trajectories and the passage of time. For this reason, I chose to sequence the journal pages as a kind of ouroboros of seasons, all the years of Ruth’s life compressed into one, as if one November is every November or as if this March and that March exist on a simultaneous plane. Within that structure, I also looked for kinds of connections between adjacent pages, from section to section, that I know delighted Seydel, the formal, the rhythmic, the alchemical: the way a red dot migrates across several pages or the mole-ish shape is reimagined; the notation of dreams and invocations of animals (as rock art drawings, as hallucinations, as actual creatures populating Queens); and of course the shape-shifting of meaning as the elements of Ruth’s world as well as the actual letters in words are rearranged.

And yet, it is all inevitable. No matter the sequence, no matter the intrusion of the editorial hand, any connection I’ve made is already there. The journal pages from Seydel’s larger project Book of Ruth is territory so dense it can be traversed by almost any route. It is, on one hand, a rich, hermetic universe: the interior life of an imagined woman in her striving to be an artist and make art. On the other, it is made of the fabric of our own world—from the paintings at Lascaux to the poetry of Emily Dickinson to the Macy’s in Queens—pulling into its force field and bonding together elements to make the most unexpected molecules.

footnotes

- All of the works included in this volume are undated though they were all made between 2000 and 2010. They generally vary in size from 6.5” × 4.25” to 7.25” × 5.25” and are all typewritten with added drawings and marks using various media. On rare occasions, Seydel sometimes typed something on the reverse, or perhaps started and then restarted on the other side.

- For the purposes of A Picture Is Always a Book and the exhibition “Robert Seydel: The Eye in Matter” that this book accompanies, Book of Ruth not only refers to the eponymous Siglio publication but also to all of the works that the curators can best ascertain as belonging to the “Ruth works.” Seydel himself comments in the interview included here about how difficult making the designation can be.

- Robert Seydel, preface, Book of Ruth (Los Angeles: Siglio, 2011), 7.

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

august 27, 2024—Oh, the chasm of meta. First, hackers hacked the original @sigliopress. As we refused to pay the ransom and meta was zero to nothing with help, @sigliopress disappeared into the abyss. A brief attempt at another—@sigliopress_affinities—was deemed “inauthentic” and taken down by meta, with none of the recourse supposedly on offer actually available. What now? Who knows. The point is…? Alas.

[...]