On the Art of Robert Seydel and the Construction of “Ruth”Lisa Pearson

affinities, 04/01/13

Robert Seydel’s art rearranges or dissolves boundaries: between legibility and illegibility, sense and nonsense, the lyrical and narrative; between fictional characters and actual personages, the historical past and the notated, recorded present; between the purely visual and its potential dissolution (or constitution) into meaning; and, perhaps most importantly, between the acts of reading and viewing. Like the petroglyphs and pictographs—the origins of human mark and meaning making with which Seydel is deeply fascinated—the words and images in his work are often inextricable and mutable; primordial and fantastic but also sophisticated and articulate: what may be enigmatic in one moment may be revelatory the next. Seydel’s work is a true hybrid, its own species.

While Seydel’s art may defy traditional paradigms, it does not reject them. His love for and extensive study of literature infuses his work in myriad ways. Both his series and individual works are often driven or ignited by a line from a poem, a philosophical observation or question, a sustained “conversation” with an author or work, or by his admiration for a particular writer as in his Series Homages. Seydel’s collages often make use of extant text which always has a serendipitous, alchemical quality: he collects innumerable fragments (newspapers, packaging, old cards, scrawled notes, etc.) which, in his hands, accumulate into a poetic and artifactual language, capable of illuminating the ordinary scraps of life, of veiling and unveiling secrets, of recording loss and of magnifying the ephemeral. In his original writings, Seydel has an uncanny feel for the multiplicity of meaning and suggestion in a single word. He exploits those tensions between meanings for their queasy emotion, their intellectual resonance, and their sometimes dark, sometimes child-like humor. As with the visual elements in his work, his texts layer, connect, and juxtapose disparate images to construct a complex experience for his readers that, while it may avoid the literal accouterments of daily life, feels true to life—as if truly part of a life. Perhaps that is what makes his characters and personas so compelling: both the poetry itself and those who “voice” it arise out of and capture something essential and ineffable. There is no conceit in Seydel’s use of literary technique, only necessity.

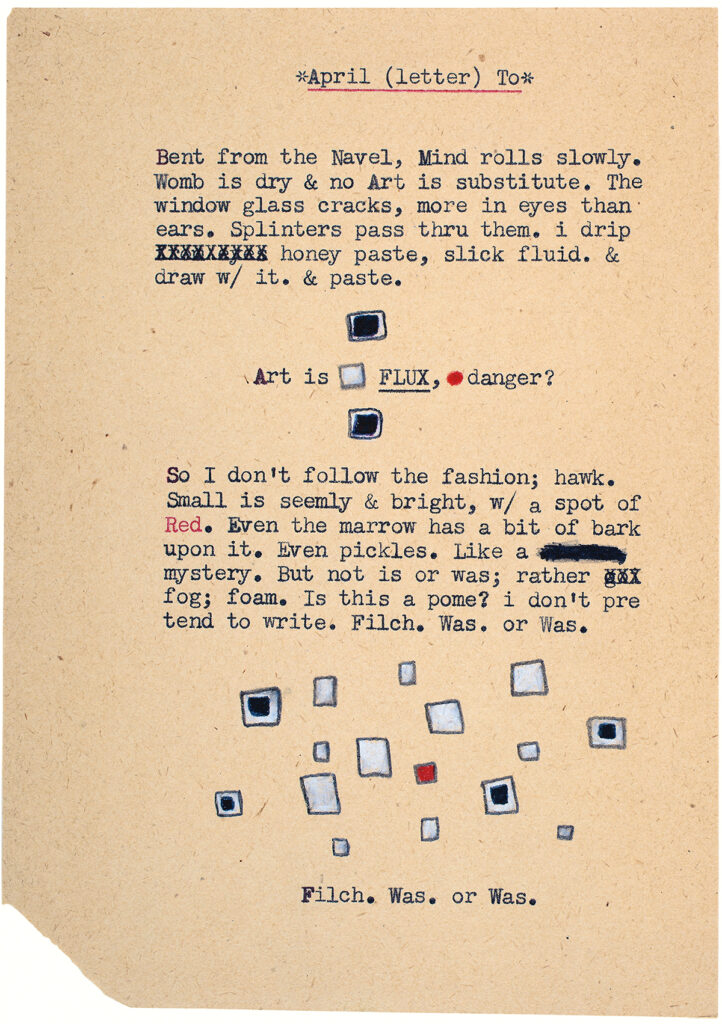

Untitled “journal page” by Robert Seydel. Reproduced in A Picture Is Always a Book: Further Writings from Book of Ruth by Robert Seydel, Siglio, 2014

Perhaps this is why I am most drawn to Book of Ruth. In this series Seydel has created a riveting first person narrative with as much emotional depth, exceptional detail, formal complexity, and intellectual provocation as a literary novel, but assembled through visual objects that “read” and—as an assemblage of fragments—beget an awareness of absence, of the unknown and the unknowable. The premise of the work—that these collages, letters, journal entries were discovered in both the Smithsonian and the suburban family garage—is already a story itself, but Robert takes it much further. While the literal details of Ruth’s life seep to the surface here and there, it is the intimacy with the details of her thoughts as well as the details in the works made by her own hand that create a stunning portrait of a woman for whom the distance between the ordinary and extraordinary, the ecstatic and the desolate, coherence and inscrutability, loneliness and embrace seems to collapse. She is, in the multiple layers of her construction, absolutely authentic.

As artifacts, the individual collages and the journal entries (typed on small, now brittle and yellowed pieces of paper) exude a power like the relics of saints: something of Ruth’s body is there, some physical connection remains. Both serve as “writings”—letters, serials, notations—through which Ruth speaks. Unlike many literary first person narratives, Ruth’s does not need the conceit of unreliability nor the detachment of reflection to force a tension between the told and untold, or reality and memory; rather, Seydel seems to locate that tension elsewhere: between the magical and the quotidian, the moment accounted for and the moments that will forever remain unrecorded, and between the salvaged and the lost. In both the collages and journal entries, that tension resides in their material and composition, in the “fact” of their authorship and in the phenomenon of its construct. The collages, like pages from an illuminated manuscript, reveal as much in their marginalia, cryptic marks, and small details as they do in the (often startling) central image; however, unlike those gilded pages, these collages are made of detritus, of things that have rusted or faded, things torn, smudged, bent, things that rarely capture our attention but here metamorphose into something alive and deeply connected to a life. Like the collages, the written journal entries are radiant and moving. They evoke Ruth’s journey through a day, an hour or a minute by writing it as if the present (in which she is writing) and that past moment (which she is experiencing again through the act of writing) merge. Yet each piece is more than a document of Ruth’s life. They are not unlike devotional icons in that they yield much upon every viewing, that they transform with the viewer’s awareness, that they are very much a part of the earthly world while calling attention to and invoking its mysteries.

Earlier this year, I had the extraordinary pleasure of experiencing Seydel’s work in an entirely unfamiliar context. In the many years I’ve known him, I’ve only seen his work as one might turn the pages of a book (in piles of cut pages, in his notebooks, in stacks of frames leaning against the wall). I’ve rarely seen more than a dozen works laid out together on his desk or on the floor at one time. There simply hasn’t been the room to see a large number of works in spatial relationship to one another. Thus, experiencing his exhibition at the CUE Art Foundation was a thrill. At CUE, I was finally able to glimpse the whole, how the pieces relate in color (the red is like musical notation) and in motif (the hare, Ruth’s symbol, travels far), how they accumulate rather than only unfold.

Overhearing conversations as well as speaking directly to strangers when I spent time in the gallery, I discovered that people seemed to feel the works spoke directly to them. Not every work, but there always seemed to be pieces with which the viewers felt an immediate and quite visceral intimacy, pieces that both challenged them and seemed familiar. While the art world often scratches its head—regarding the small scale, the prolific, the rough surfaces, the multiple meanings, the playfulness and sadness, the reclusive process—there are other audiences for whom these qualities are truly magnetic.

April 1, 2013 Postscript

I wrote this piece when Robert was still alive and long before I published Book of Ruth—almost a year before Siglio had even published its first title. Robert’s work was one of the inspirations for starting Siglio and Book of Ruth was a cornerstone for the press in its absolute hybridity, its rigor, its imagination, its unwieldiness, its unusual but undeniable beauty. I’m posting this essay now while the blog is focusing on “Women Artists & Hybrid Forms” because Ruth is an artist working in a visual-literary mode, and while she is Robert’s alter ego, she is, to my mind, authentically female. Robert understood this certainly in the ways in which he conjured emotional experience, but for him it was a question of form, too: “There’s both a quickness and interiority as well as verbal abundance in the women artists and writers I admire that I think is different in kind from men, and I’ve tried to access that as best as I know how to. … The other quality I’m after, which I think women writers in particular embody, and which in an almost paradoxical way is related to this idea of quickness, is a type of chiseling of language, as in the poems of Dickinson and Lorine Nediecker and even Stein in her idiosyncratic way. Ruth tends both ways, as I do generally—towards interior verbal excess and also towards a sometimes sharp and sculpted rhetoric, at once oblique and specific.” He talks more about the complications and opportunities of creating his work in a female “form” in his interview with Savina Velkova. I had seriously considered including Ruth Greisman in It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers, but decided against it in the end. She will, however, be included in an upcoming post that extends that collection to include those I couldn’t in the original publication.

© Lisa Pearson. All rights reserved.

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

May 27, 2024—Eggs, books, etc.: The first book in siglio’s new habitat is just about laid. Our local snapping turtle George perambulated the house in driving rain, determined and curious, then laid her eggs at our doorstep. Do snapping turtles and publishers share common traits? Oh, so very, very slow. Reportedly testy but actually timid. A group of them might be a bale, nest, turn, dole, or creep—though ours seems solitary. Only 10% of her eggs will survive as hatchlings. Make of it what you will. Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers goes on press very soon. One sleeper said to Calle: “I’ve often dreamt of an egg that was enormous ovoid transgression. The original sin of Adam & Eve is a hard-boiled egg.” Meanwhile, many sightings of goslings, kits, poults, and one fawn too: how easily the others propagate, alas.

[...]