Imagination’s ArtifactsOn the Art of Keith WaldropRobert Seydel

excerpts, 07/31/23

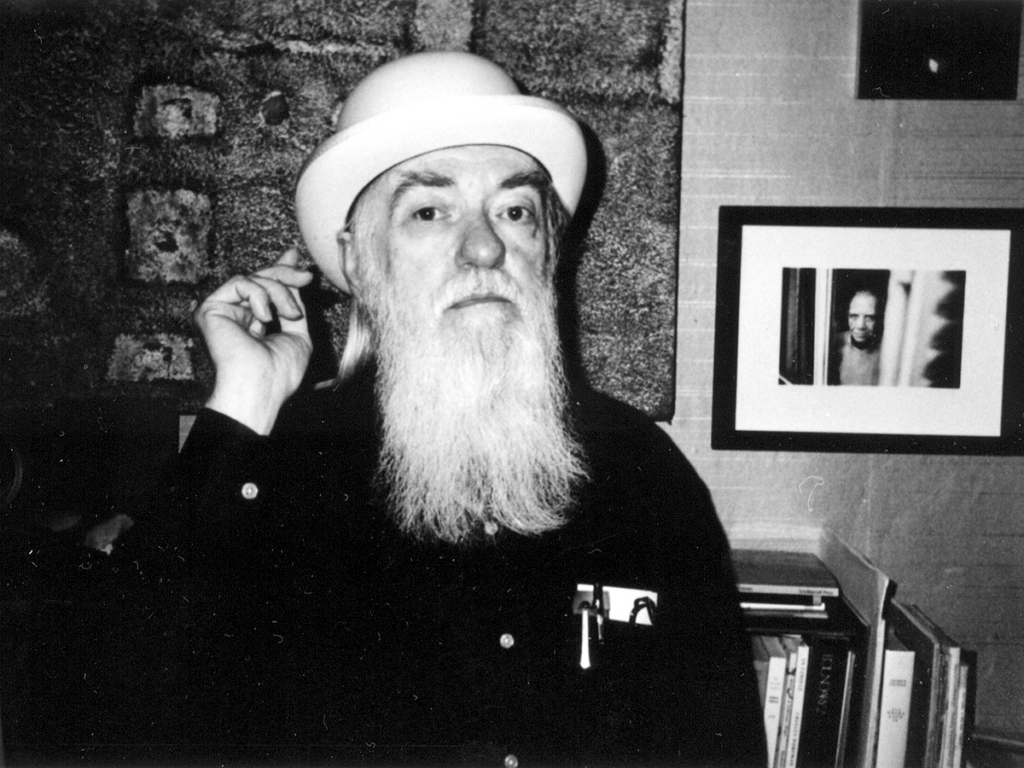

photo: Claude Royet-Journaud. The photograph visible on the right is of Edmond Jabès, taken by Maxime Godard.

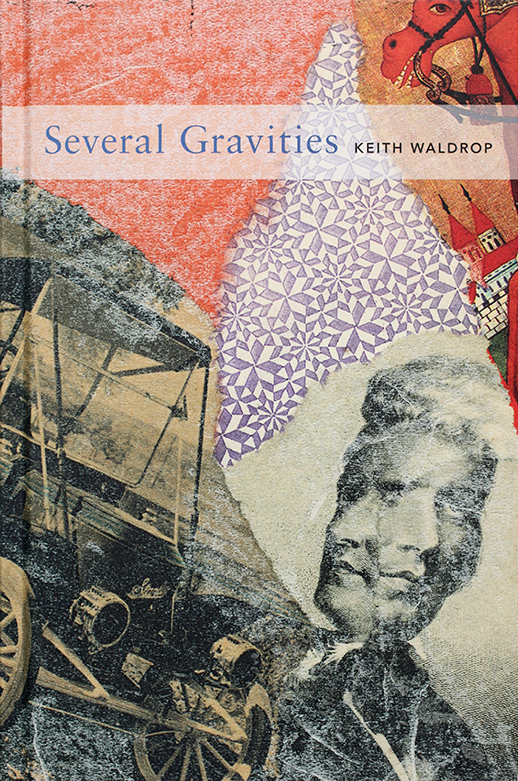

Originally written for and published in Several Gravities by Keith Waldrop, edited by Robert Seydel, Siglio, 2009. All rights reserved. © Robert Seydel.

two words (flung) divide objects

the image formed without being seen—Claude Royet-Journoud

from Theory of Prepositions,

translated by Keith Waldrop

Keith Waldrop belongs to that rare company of poet-artists who form across the centuries a hybrid species and a band of fellow travelers. Such figures delineate for us a picture of the imagination as something more fluid, greater and more unwieldy, than the categories—literature or art—by which we customarily differentiate creative endeavor. A particular, somewhat uncanny type, the poet who is also an artist has a distinguished pedigree, from the Chinese literati of the Tang to more recent incarnations. Eccentricity is part and parcel of the lineage. A prolific beauty—a beauty in a sense composed of the prolific—shapes their work. Multivalent and rife with the dispensations of the plural, the more complete art of a figure such as Waldrop trembles on the cusp between the sayable and the seeable, the thing and its name, the visible and the invisible. From Wang Wei and William Blake to Hans Arp and Henri Michaux, distances of culture and period seem to matter less than the impulse they share: to bind up the verbal and visual and to enunciate across linguistic and pictorial fields a shared heritage, at the origins perhaps of an alphabetic writing in glyphic mark-making.

Two (or more) mediums gather together in such artists, in a kind of dance that rejects differences of medium, intention, and feeling. What is visible in the opening they provide is a specific freedom, of conception and inspiration, of imagination as larger than training or medium. It is a wilder form their works often speak—in consort, but also in their separations. Memory traces of that other gesture—poem or picture—remain in the mind. A multiple ground rises there as an originary confusion between the word and the mark, the song and the gesture, sounds and colors. This is not turmoil, or is not necessarily turmoil, but an opening rather, often ecstatic, into spaces of a perhaps primary coalescence of mind in its high vision and density of response to world.

There is, although it is hard to put one’s finger on it, a subtle differentiation in our reception of and in the actual aesthetic feeling and conceptual space of the visual work of a poet such as Keith Waldrop, as against the canvases and pastels of someone like Irving Petlin, for instance. I love Petlin for his literariness, as I admire Kitaj for his. Both however are painters first, despite the latter’s remarkable Diasporic writings. The depth of their relationship to the language arts goes far beyond, but nevertheless remains linked to, the ongoing traditions of illustration. Like that of Michaux and Antonin Artaud, among others, Keith Waldrop’s visual work is of another order, and encompasses a space of further mystery, dependent on, infiltrated by, but nevertheless set apart from the linguistic function so determinative in these artists.

Contamination striates the work, as a kind of lovely virus. Traces of the linguistic adhere to the picture, pollute, in fact, both the pictures themselves in their procedures and our cognition of them. That contamination—a kind of hybridization, unmoors the picture. It is loosed and set adrift in a field of linguistic-visual codes that refuse semantic and other closures and that are only partially visible in the work itself. Traces of another field of being and mentality slip through the work, and accord it a type of secondary atmosphere. It feels, in some way hard to countenance, less a work of art, though of course it is that too, than an artifact of the imagination in communion with its own expansions and possibilities.

The visual work by a writer oscillates in a way other kinds of work doesn’t. (This is true as well of the writings by certain artists, such as Kurt Schwitters or Günther Brus or Bern Porter, which do not equate with what has recently come to be called Artists’ Writings.) The picture goes a little bit daft and unmoored. Its roots—those it has—lie more in fields of play and delight than otherwise; an air of occasionality and deftness, perhaps “lightness” or quickness, in Italo Calvino’s words, rather than labor, accompanies it. The forces it shapes and accedes to seem closer to the artistic and experimental mind in its first precisions. Revelation of the primacy of the imagination seems to be such work’s central meaning, beyond specific—but perhaps secondary—intentions located at its surface.

*

The alliance of Waldrop’s writings to his pictures and of his pictures to his writings is marked by meaningful cross currents, both as regards his procedures and his general artistic stance. Air in one is coeval with the air in the other. Borders and horizons sway; the unbeheld, a space of proximities and distances, desire above all, melancholy above all, mark both picture and poem. What is enunciated and what is withheld in one medium rhymes with the enunciations and absences in the other. I don’t know that Waldrop would necessarily agree with this, or with the general tenor of these remarks. I have heard him say, for instance, “I turn to collage to get away from words.”

And certainly Waldrop is that rare figure—a poet’s poet, inherently graceful in his utterance, in both poetry and prose, and somewhat hermetic, sage-like, very beautiful in his hesitations and quiet delivery of both self and poem. But his collages and other visual work share these traits and participate in the same alembic as his poetry, precisely as though, as one says, they are poetry by other means. Jean Cocteau famously wrote in Dessins, “Poets don’t draw, they unravel their handwriting and then tie it up again, but differently.” In Keith Waldrop’s case, what is unraveled is not perhaps handwriting (though it is that too), but the poem as work of collage—a kind of aerial feat that attempts to delineate the unbridgeable spaces between things through the construction of artifacts into form, both visual and verbal.

This binding of form from fragment, central to his art, is fascinating. It’s impossible, as a matter of the related writings woven through Several Gravities—as sign posts for the poet’s thinking about the image—to excerpt from his more strictly collage-type poems. They are of a piece and hold so tightly to their shaping that excision equates with subtraction and sunders their original, densely shaped intentions. Excision, that is to say, unbinds them. Poems such as “The Chapters Together” and “The Cake He Typed,” indeed almost the whole of a book like The Garden of Effort in which these poems are situated, are radical works of collage held together as it were by a structure of tissue—consciousness—impossible to pull away from, lest the whole (their musics, both of sound and of meaning) collapse. What they affirm is, against wreck, as Ezra Pound wrote near the end of his life, “the gold thread in the pattern.”

Sound and meaning as high construct, form as vision, have precise analogue in Waldrop’s visual work, where tissue and other diaphanous matter shape webs and nets across the surface of the picture. His collage is a masked and floating thing. Scrawls, calligraphic and nearly linguistic, can resolve themselves into cracks of the tissue that delineate their atmospheres. Bubbles of shape that verge sometimes on the unformed, on no-form, or the barely legible, extend out from solid architectural fronts. Sky, that is rarely horizon, and across which being floats, is a webbed space full of ghosted impressions. His collages, visual as well as verbal, reveal quiet tensions, nearly biologic. Veil upon veil layers his work, composing its densities, all of which are paradoxically light. There is in this work occlusion, a smoky atmosphere; distances recede, objects float. The gossamer air in many if not most of his pictures is romantic and clouded. That the postal mark and the stamp, the fish and the duck, are key elements in his iconography, is all to the point. Being crosses space, through a variety of airs.

In collage, opacity is the norm, defining a solid architecture through a series of abutments. Certainly Waldrop employs this formal structure on occasion, but he more typically enunciates his picture through transparency. Ghostings, hauntings, veilings, falling and ascending figures, drift are central terms for Waldrop, all concerning the in-between, in part the unbeheld. “He craves an interval,” as he writes in his recent book-length poem, The Real Subject, an opening, that is, between two (or more) terms, forms, or states of being. That may well be the defining space a poet-painter, as type, seeks in general, in his rejection of the determining accommodations the imagination must make inside the limits of any single medium. Constructed from multiple sourcings, Waldrop’s art obeys its own laws of composition and is related in one sense to cottage industry stitching. The strand is determinative. This is the condition of collage generally but sums up Waldrop’s in particular.

*

A consummate poet, alive to the hesitances and silences at the heart of language, Waldrop has simultaneously been making visual works of art for more than thirty-five years now. His primary medium is, as he’s said, “collage, my great delight,” although he has also made any number of drawings, numerous small box and vitrine assemblages (one of which, his largest, is featured here in two photographs by Naomi Yang), and has as well been using the camera recently to record incidents of form and space found beneath his feet. Several Gravities is concentrated on his collages, and in fact on one specific strand of them, with little reference to chronological development. There is reason for that—many, if not most of them, are undated. (And rafts of them have gone out into the world, as gifts and, when not, most nearly as gifts, he charges so little for them. Gifting, gestures of his generosity, as in potlatch—the wealth of his productivity—seems part and parcel of their economy.)

But chronology and development in fact seem beside the point when confronted by the beautiful and daunting accumulation of his pictures. They are stacked in rows in his attic studio and are piled on his two small worktables there; they spill out of the many boxes on and under the tables and upon the couch and are stacked and displayed on a variety of shelving units. They are tucked away, hidden, and heaped-up—“This is the mess I’ve made. Under it all is a fire I did not set,” as he notes in a poem excerpted here on page 76. But they are also distinctly present as both precious objects and as visible energy of endeavor, and in their totality represent an inspired and wonderfully dense accumulation of a life given over to that impersonal “fire” that is art’s name perhaps in the long reach of it. His pictures are also, of course, more traditionally hung, salon-style, in a variety of found frames, on the walls and throughout the stairwells of his and his wife, the poet and translator Rosmarie Waldrop’s, home. They jostle there with works made by a host of distinguished friends, the poets and painters and photographers of their company.

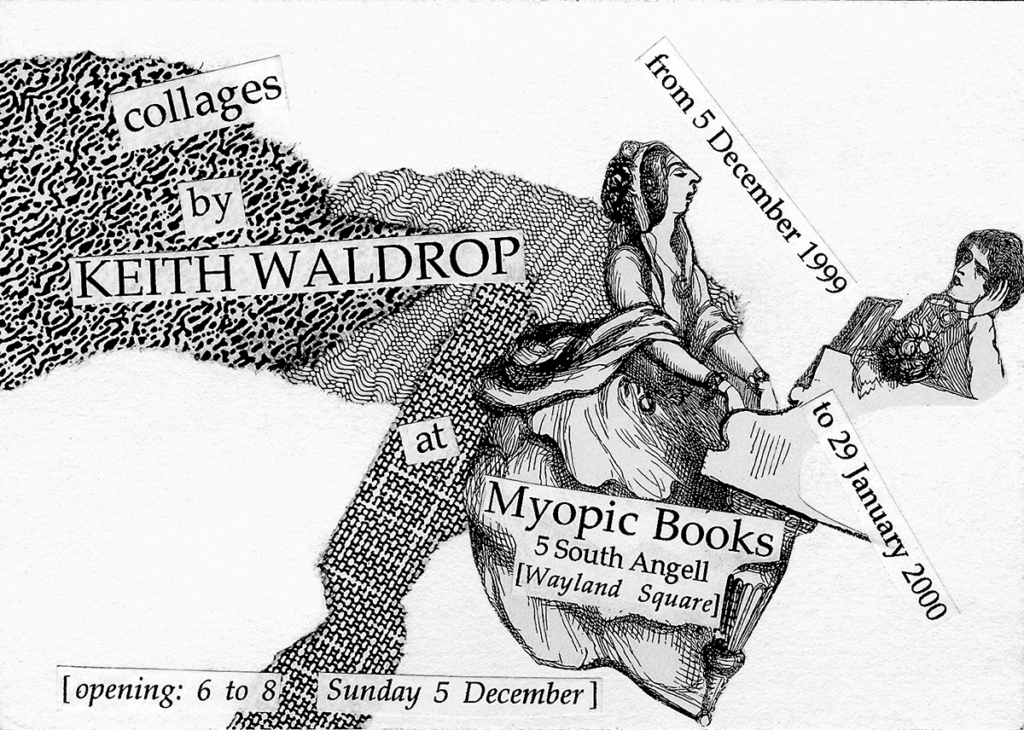

He first exhibited his pictures publicly in 1979 at the Anyart Gallery in Providence, Rhode Island, and has made for any number of exhibitions since then numerous original collages to be used in reproduction as invitations. He has likewise fashioned works for the covers of a number of Burning Deck titles (the Waldrops’ renowned small press) and for other publications, including books of poems by Clark Coolidge, Ludwig Harig, Dallas Wiebe, and both of the Waldrops themselves. Three of the most beautiful of his book covers, alongside an exhibition invitation, are reproduced here. The second and third life of this body of work are part and parcel of the artist’s various extensions.

The pictures in general are small, sometimes infinitesimally so, and are rarely larger than the small tabletop at which he works, high up in a cramped studio space under the eaves of his home. Often, as with his writing, they come in series, like the extensive Ann Radcliffe or Metro Tickets works, neither of which are represented here. His source material consists of a matrix of the contemporary and the antique. Time both is and is not part of their coding, in that a kind of “continuous present,” in Gertrude Stein’s phrase, seems to be their condition, which in another dispensation is carried by depictions of doubling.

Comic book figures and horse and rider pairs run through many of them. Hands regularly reach down into the collage’s field and are both a pointing in the Proustian sense and an acquisitive holding, and are of course indicative as well of a creative charge consonant with illustrations of the Book of Genesis. A garden or pastoral scene vies, often in the same image, with an urban architectural density. Figures regularly float from one space to the other, opening precisely to Waldrop’s central care for “the interval.” Registration marks on stamps are concrete evidence of flight; bodies in space and animal forms, the quick gestures of a calligraphic marking, free-floating alphabetic stutters, like small Dada sound phrasings, are all evidence against gravity and designate that in-between space, a liminality, that is so central to both his visual and poetic lexicon. Marvelous, romantic, and contradictory in their shapings, his pictures gesture toward, accommodate, and open up free territories of drift and dream. In their fullness they spell both an architecture of contemplation and a vision at odds with the solid structures of time.

*

But I would like to think that it is the Waldrops’ home in Providence, its cloistered and full atmosphere, that may in fact represent the couple’s central work of art, “a small provincial museum,” as Waldrop calls it in his poem “Antiquary” (reprinted in his essay here, “A Matter of Collage,” page 11). The primary exempla of the artist’s work and life might be said to reside there, in situ, as environment, an integral space of mind and art, and a contemplative, dusty, and rich assemblage. Their Elmgrove house is something like an Ark, bent over and listing and beautiful in its accumulations.

A book, any book, is hard put to replicate or even suggest such an environment, nor have we tried to do so here. Such grand works of the imagination as Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers in Los Angeles and the postman Ferdinand Cheval’s architectural wonder, the Palais Idéal in Hauterives, France, are impoverished images in reproduction. The awe their achievements inspire is emblematic of lives devoted to fashioning, on earth, a sacred and simultaneously domestic space. The sacred and the domestic are coexistent in the Waldrop home, and are central as well to Keith Waldrop’s art, both in its procedures and its contents. Images of saints jostle against ducks there. The juxtaposition of a matchbook cover with a melancholy child’s face, the rich patternings of hand and tissue and figure, realign the seams of hierarchy and shape new hieroglyphic matter, composed simultaneously of the perfect and the fallen, which may be equivalent in the end.

From the first, then, a book like this—perhaps all books on a certain type of artist—of necessity fails. It can supply only intimations of the artist and of the environment that his art and his love—desire, Waldrop often names it, which is knowledge, or its effort—fashions around and through himself. That failure is sign also of art’s failure generally, noble as it is or can sometimes be. It is an impossible reaching—in Bataille’s sense—towards that which rejects containment and that remains nevertheless art’s desire, its risk and hope, as it is explicitly in Waldrop’s work.

*

I sometimes think that collage is in fact the privileged medium of melancholic types, who hold their lives and the weight of its failure and incomprehension as sign of the impossible desire of both art and being. Collage begs a reconciliation between world and art that is rarely more than a bait and switch—a trope, not a truth—of irreconcilables. Resurrection is both its labor and the terrain of its hope. Pasting, as procedure laden with metaphor (think of Ray Johnson’s Potato Mashers), is a binding that can never, despite what I noted earlier, bind up all matter into a sovereign, single, and healed space. Fragments align only partially, and their alignment is always fragile. Saturn is “in love with the productions of time,” just at the point where they flee away. Both gravity and gravitas reside in Albrecht Dürer’s figure. Walter Benjamin and Joseph Cornell were dream-addled melancholists and collagists of the first order. Both bind up materials against ruin. There is in each of them, and in Waldrop also, what the latter refers to in his book Haunt as the “sorry history of faint blue galaxies.”

In Waldrop’s writings there is more space than otherwise, like the silences between stars. There is luminosity, but also a dark well, between phrase and phrase. Interstices open between them. Every word in a Waldrop poem is hesitant, non-declarative, and opens on vertigo. Melancholy closes in on the possibilities and impossibilities of the word. In his visual art glued tissue serves a similar emphasis—it shapes both interstices and the “faint blue galaxies” that ride there. There is an unmistakably major tone in Waldrop’s poetry that is nevertheless tempered by, perhaps even negated by, uncertainty and the swayings and mercurialities of a language (and mind) ruled by drift. A declarative power, which is collage’s terrain also, in its way of pointing to and positing unique instances of the real, is dialogically contrasted by another power, that is both negative and negating.

Throughout Waldrop’s work, both visual and verbal, a kind of No walks, like an old man muttering to himself in the twilight. “Everything is flying away from me,” he notes in his poem “Sections.” His saints, and there are many of them, are melancholy saints. A world in flight is the negative trope, in contradiction to the binding efforts of collage’s original dispensation. Dust walks across the surface of the picture and is bound in glue to it.

What is most marvelous perhaps in Waldrop’s art is this No, which I find rare and uniquely his. It takes a poet-painter perhaps to fashion a practice this philosophical in its implications. Antonin Artaud’s unruly and mad late drawings of human faces—his own and others—are to the point. “The human face has not yet found its face,” he says. And because Holbein and Ingres or “any other painter in the history of art” failed to recognize this, their depictions of the human countenance likewise fail. His own drawings, he says in “The Human Face,” are therefore only “sketches, I mean soundings, or staggering blows in all directions of chance, possibility, luck, or destiny.”

A Waldrop picture in this sense regularly turns on the lip of refusing itself—often shaping a free-fall of forms in a kind of gestational space. His pictures are haunted by what they are not, which is to say that they ride along the edge of another field of possibility. In his beautiful, and perhaps too little read fictional memoir, Light While There Is Light: An American History, he wrote:

All my family, and Julian is our type in this, have a streak of the unworldly. For us, God’s sphere of action and the local scene rarely make contact, separated by the patrol of cyclonic storms marshaled overhead by the great Westerlies, or directed—we disagree on terminology—by the Prince of those powers. Once in a while, however, a spark manages to pass from one sphere to the other.

That passage across is the terrain of an unsayable something, the verge on which all his work uniquely balances. The domestic and the sacred hold there, but as in a glimpse, one quick calligraphic gesture. At the heart of Waldrop’s collages is an argument with the visible, which is severed, ungraspable, and fleeting. The visible is both the desire of the work of art and its central being, bound up one in the other. But the real unmoors the collage picture, being in a contradictory relationship with it. Form even more than figure is always “flying away” in a Waldrop collage. Gravity is its condition, but gravity is several.

see also

✼ consideration:

“Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera … achieves the hidden aim of all postmodern work. Namely, befuddling the reader with the dilemma: is this sheer brilliance? Or merely incomprehensible nonsense?”

[...]