Floating Between Past and FutureThe Indigenization of Environmental PoliticsLucy Lippard

excerpts, 10/06/17

Originally written for and published in About to Happen by Cecilia Vicuña, Siglio/CAC, 2017. All rights reserved. © 2016 Lucy Lippard.

“Words are acts”

—Octavio Paz

Although Cecilia Vicuña’s art is thoroughly ensconced in the present, she is also an “old soul.” Her ancestry may include the indigenous Diaguita from northern Chile, as well as Basque, Irish, and a Spanish family that goes back to seventeenth-century Chile, which could well mean an early mestizo (mixed) line in all of the southern Americas, up through Nuevo Mexico, as Spanish colonials propagated with local peoples. Vicuña has identified with Andeans since she was a child. When she was six, the Inca mummy of a sacrificed boy was found high in the Andes and schoolchildren were taken to see it at the Museum of Natural History in Santiago. She recalls that “they had turned him into an ‘exhibit,’ an ‘object,’ but I saw it was me, exactly like me, and I believe that’s when my identification with the ancestral world began.”

In Basque, vicuña means mountain goat, and she began to think of herself as an Andean animal when her friends in Colombia converted her name into a verb: “ahi viene La Vicuña a Vicuñar” (here comes the Vicuña to do her Vicuña thing). In 1977, she painted “La Vicuña,” a nude self-portrait locked in an embrace with her namesake, sharing a pair of eyes. In 1990, she titled a poetry book La Wik’uña, using the Quechua spelling.1 Vicuñas live at almost celestial heights and are said to be born at the sources of springs. Their wool was sacred fiber, woven into the source of all Andean wealth. Thus the artist’s family name, her very identity, evokes weaving and water—two of her major themes. As Peter Skafish has written about Eduardo Vivieros de Castro’s theories, Amerindians:

“who live in intense proximity and interrelatedness with other animal and plant species see these nonhumans not as other species belonging to nature, but as PERSONS, human persons in fact, who are distinct from ‘human’ humans not from lacking consciousness, language and culture—these they have abundantly—but because their bodies are different, and endow them with a specific subjective ‘cultural’ perspective. … Thus the idea that culture is universal to human beings and distinguishes them from the rest of nature falls apart.”2

Years later, Vicuña discovered that the child mummy that had so impressed her had died with red threads in his hands3 and had been buried alive next to the glacier that is the source of the Rio Mapocho. The artist was born in a clinic in downtown Santiago, by that same river. Water, red threads, and the Rio Mapocho are constant presences in her art—connective tissues binding and bonding present, past, and future, as well as the varied landscapes in which she has lived and worked. Threads are not only connective—textiles or texts, as she has often noted—but they were inspired by quipus, the Incan narrative and accounting devices consisting of a central line (a kind of horizon), with threads below and above. Vicuña has likened the quipu to a palindrome. It can change, knotted and tied over and over, transforming in place, like her own fragile and temporary artworks. Her piece in the upcoming Documenta is “the story of the read thread”4—a Quipu Mapocho following the entire course of the river, a project initiated in March 2016 at its mouth, la desembocadura, which is currently threatened by a MegaPort development that is dumping chemicals and destroying the beach. The piece will culminate in a performance at the glacier.

In 2014, Vicuña and her partner, poet Jim O’Hern, created a video with the goal of recovering collective memory and environmental responsibility through oral traditions. It is titled We Are All Indigenous, though Vicuña adds, “some have forgotten”—(that would be most of the U.S. population). For all its welcome sense of unity, this notion is problematic among the tribes native to the United States, where commercially-driven wannabes and Asian imports plague North American Native artists. (The “my-great-grandmother-was-a-Cherokee-princess” syndrome is cause for snickering in Native circles.) Pan-Indian movements notwithstanding, North American tribes have struggled for centuries to maintain their cultural individuality and sovereignty in the face of forced assimilation. Non-Native artists trying to pass, and appropriating indigenous symbol and image have come in for some ferocious criticism. There are current coalitions of Latin American and North American indigenous activists, for instance, Idle No More, founded by four women in Canada and now a vast global movement to protect land and water from fracking, pipelines, and nationalist and corporate greed. Latin American indigenous communities, for all the crimes against them, are often more culturally autonomous than those further north, and their political situations vary from nation to nation. The survival of indigenous peoples in the face of incredible odds may have created a model, of sorts, for those desperately trying to raise consciousness about impending environmental disasters.

Candice Hopkins, a Native Canadian curator, writes that there is a “growing interest in Indigenous art internationally. We know, from experience, that these interests emerge at times when Western culture and ideologies are in a state of crisis. Right now that crisis is environmental and, somehow, it is the latent recognition of indigenous knowledges and cosmologies that might save it.” But, she reminds us, “There also needs to be a responsibility to not just borrow these forms, but to consider how what you do might enable the very people from whose practices you are borrowing from … the perspective that everyone is indigenous can be harmful, as it erases or speaks over the voices of those who have been quite radically dispossessed. Is it the same as the call for Black Lives Matter being met with ‘all lives matter’?”5

But Vicuña’s notion that we are all indigenous goes back into deep time. In 1989, she wrote a poem that accompanied a precario sculpture at Lake Titicaca: “The Inca is about to be/and the ruins of the past/are the model for the future/being created by our/remembering.”6 There is nothing specific about her appropriations, if that is what they are. Her works “look indigenous” not only because of her profound sense of communion with Chilean Native cultures—even as she decries the poverty imposed by colonialism and its consequences—but also because most non-Natives are so ignorant about what really is indigenous. Just as her poems take language apart to discover new and restore old meanings, her objects evoke rather than imitate. As Surpik Angelini has written, she “avoids both mimetic and exotic representations of Amerindian culture … Her voice, breath, accent, gestures, signs, traces, and marks show us how these elements conforming the ‘aural’ dimensions in her aesthetics, far from being abstracted from reality, vividly evoke the artist’s actual experiences with Andean people.”7

Vicuña often works at the confluences of waterways, a metaphor for her connective aesthetic. She has woven her threads under water and tied rocks together in streams, paying homage to their endless movement and transformational qualities, reflected in a poetry book titled Unravelling Words and the Weaving of Water (1992). She often finds the cross form unintentionally appearing in her art, and notes that it is the essence of weaving, of crossing cultures, or national boundaries, or art world categories. An installation at Exit Art in New York in 1997—The Water Wants to Be Heard—was about the circulation of water in the city, offerings to the rivers, the gutters, the puddles. It was also about listening to nature. The phrase has become a slogan for environmental actions. Her friend Sabra Moore recalls small shrines next to hydrants in the city streets, “paying homage to a life source that most of us took for granted.”8 The Agua de Nueva York project included tiny “rafts,” braving trash and commercial vessels, recalling the crossing of seas and cultures by the Kon Tiki. She also warns that water was privatized in Chile by the Pinochet dictatorship, while “mining corporations and private enterprises have appropriated the rivers,” evicting indigenous fishermen whose ancestors have been there for millennia. Combined with global warming, this has “created havoc, drought/floods, disaster after disaster, the latest one at the Rio Mapocho.”9

She cites “these old stories that keep coming back in one form or the other … my poetics have always been indigenous, performed in the Andean spirit that embraces wisdom from all corners of the world. I discovered Taoism as a teenager, and that philosophy increased my passion for indigenous thinking, which in time I expanded to include Dada and Surrealism, which always brought me back to ancient knowledge.” Respectfully sharing a spiritual approach with her indigenous sources, Vicuña sees herself as the receptacle of ancient knowledge, which she then translates into a very contemporary idiom. Her art is not easily categorized. She’s neither a poet who makes art, nor an artist who writes poetry. Her art is a naturally fused amalgam of word and act in which she not only translates, but becomes an archaeologist of language, excavating, dissecting, recreating meaning, and communicating it to the inhabitants of today. Her “performances” or “eco art actions,” which date from the 1960s, have been called “conceptual” and “dematerialized.” In the 1970s, involuntarily exiled from Pinochet’s Chile in London, then Bogotá, and finally New York, she organized and participated in any number of protests—both political and aesthetic—against the fascist regime. This confluence of ancient beliefs and current politics is typical of Vicuña’s art, which she sees as an homage to the “despised peasant ideas” that secretly fueled centuries of resistance against colonialism. One aspect of her work, that is unique in the realm of so-called Conceptualism, is its emphasis on connective communication. Vicuña bemoans the fact that “complex public conversation” is disappearing. She identifies with “marginal people—children, the insane, the uneducated,” often incorporating their voices into her work. She leads children’s workshops, and constantly engages her “audience” (in this case the word is accurate for art as much as for music). In her 1980 film, What Is Poetry to You?, she interviewed prostitutes, workers, and residents of the poorest barrios, receiving responses that inspired her to keep asking, keep listening.

Precariousness is increasingly a description of human life on the planet, and precariousness is Vicuña’s element. Her art balances on the littoral or liminal edge, where land and water meet10—places like New Orleans, where the devastation by Hurricane Katrina and the BP Gulf oil spill, five years later, is ongoing.11 The history of water in Louisiana, forever entwined with the Mississippi River, the Gulf of Mexico, and the hidden bayous, provided fertile ground for Vicuña’s work in this exhibition. La Noche de las especies, la mar herida nos mira (The Night of the Species, the Wounded Sea Watches Us) recapitulates an earlier drawing, 120-feet long, executed in Chile in 2009. It is based on the death of the ocean, and its rebirth: “The poems at the bottom of the sea are bacteria dreaming the sea back to life.”12 The rapidly eroding Louisiana coastline predicts the waters’ triumph over human engineering, suggesting another beginning, birthing a new species less arrogant than ours … or perhaps a recreation of “us” so the cycles can begin again. Vicuña dedicates her new site-specific installation—A Balsa Snake Raft to Escape the Flood, constructed of basuritas (detritus)13 from the coast—to the climate refugees in and on the Gulf, especially the indigenous communities.

If we are all indigenous, we are also all immigrants. Displacement from original lands is an integral part of modern indigeneity. Vicuña has said that “language is migrant,” and in one of her palabrarmas she imaginatively parses the word “migrant” into the Latin mei (to move) and Germanic kerd (heart), arriving at “changed heart, a heart in pain, changing the heart of the earth. The word immigrant really says ‘grant me life.’” Then she adds the proto-Indo European root of “grant”—dhe—meaning “allowed to have,” which she connects to the roots of law and deed, and sacred rites.14

In the arid Southwest, where I live, the history of the land and its indigenous peoples are far more visible than in most parts of the United States, more like Latin America. As we attend the dances for rain that remain part of Pueblo cultures, we are constantly reminded of the millennia of successive droughts that formed our landscape, and the desperate urban and rural planning that is surfacing in southwestern and coastal cities, and in agricultural communities. Vicuña’s Cloud Net (1998) evoked the eternal safety net necessary to survival, recalling the Cloud Terraces in Pueblo rock and kiva art, and shrines in the landscape to clouds and the deities, called kachinas, who live there. Of course water is life all over the globe, as inhabitants of non-arid regions are finally beginning to realize.15 With the increasingly dire effects of climate change breathing down our necks, our national sense of invulnerability and exceptionalism is eroding along with our coasts. The nearing upheavals are made visible by artists whose ecological consciousness and social consciences have led them into deep water. As rivers join the sea, so Cecilia Vicuña and her peers hope to reunite society and nature on an indigenous model, joining Native peoples all over the world.

from About to Happen by Cecilia Vicuña, Siglio/CAC, 2017

endnotes

- Vicuña believes that the similarity of Basque and Quechua was probably a “phonetic coincidence. The two names are not connected linguistically or historically. Since Quechua was not a written language, the Spaniards ‘heard’ the word ‘vicuña’ in the Andes, and they wrote it in Basque.” (Personal communication 5/24/16)

- Peter Skafish, “Introduction” to Eduardo Vivieros de Castro, Cannibal Metaphysics, Minneapolis: Univocal, 2014, 12.

- Vicuña’s sculptural installation Aural (2012) was dedicated to this child.

- “Read” instead of “red” began as a typo, but it kept “repeating itself,” so she decided to keep it.

- Candice Hopkins, personal communication, May 2016.

- Quoted in Lucy R. Lippard, “Spinning the Common Thread,” in M. Catherine de Zegher, ed., The Precarious/QUIPOem: The Art and Poetry of Cecilia Vicuña, Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1997, 15.

- Surpik Angelini, “Cecilia Vicuña: The Aural Dimension/La Dimension Aural.” In Artlies, Fall, 2000, 54.

- Sabra Moore, personal communication, May 2016.

- Personal communication, May 2016.

- See Bruce Barber, Littoral Art and Communicative Action, Champaign, IL: Common Ground, 2013, for a theoretical artist’s ideas relatable to Vicuña’s work.

- I lived in New Orleans in the late 1940s and recall plunging tropical rains that flooded the streets with an abandon unfamiliar to a Yankee, as well as snakes, gravestones, wild oaks, and Cajun talk on the Bayou Barataria. For the past twenty -three years I have lived in New Mexico, where agua es vida (water is life) is a constant refrain. These extremes inform my ecological consciousness as Latin America and New York have informed Vicuña’s.

- Personal communication, May 2016.

- Over the years Vicuña has often called her ephemeral sculptures basuritas, or little garbages, little rubbish.

- Cecilia Vicuña, “Language is Migrant”: www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2016/04/language is migrant.

- Florida ran out of water a few years ago in a massive drought, bringing home the extent of a crisis often confined to the West, and today sea water is infiltrating the aquifers in the Everglades as seas rise.

see also

Books

Hinge PicturesEight Women Artists Occupy the Third DimensionWorks by Sarah Crowner, Julia Dault, Leslie Hewitt, Tomashi Jackson, Erin Shirreff, Ulla Von Brandenburg, Adriana Varejão and Claudia Weiser, and essays by Andrea Andersson and Alex Klein

Books

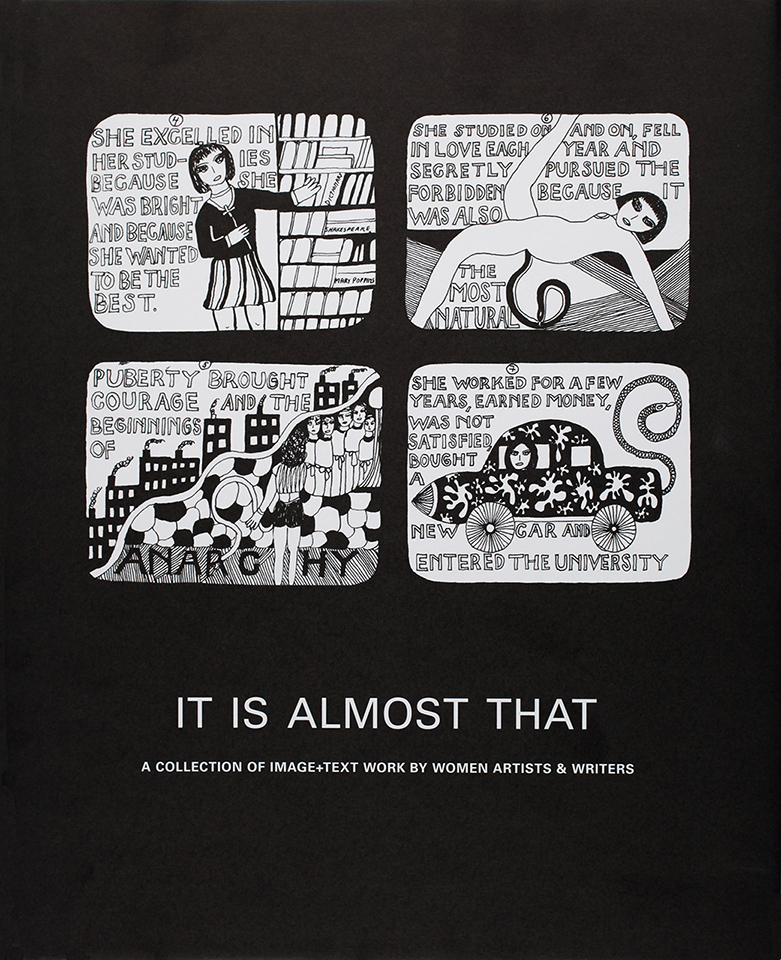

It Is Almost ThatA Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers

Books

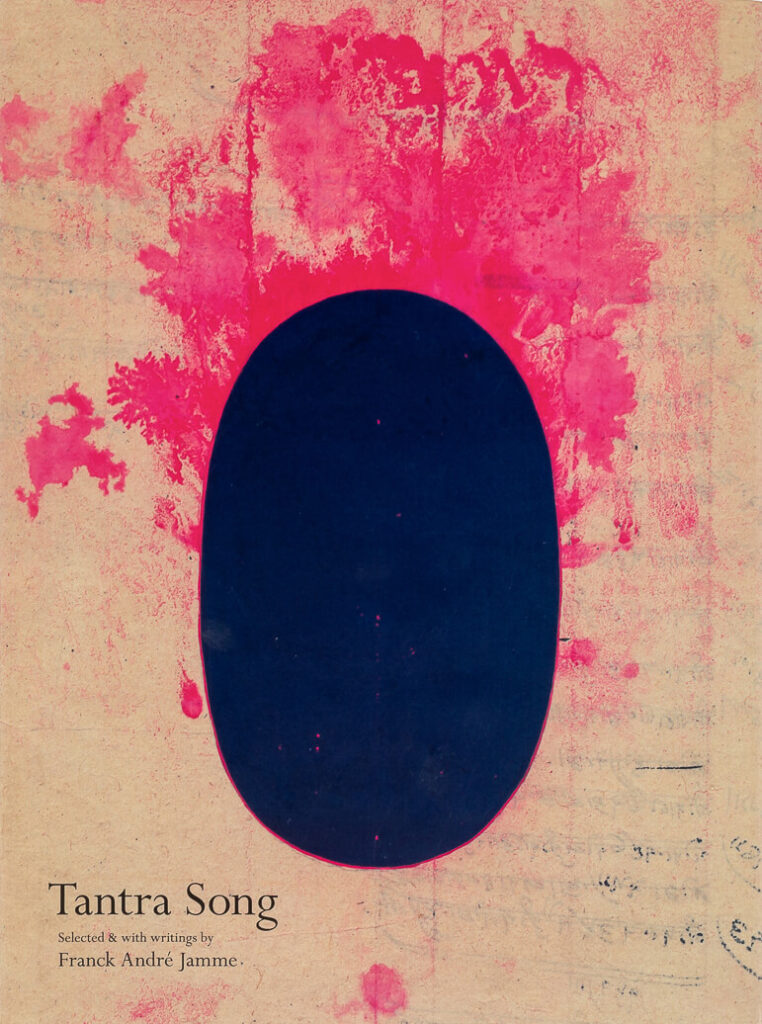

Tantra SongTantric Painting from RajasthanTranslated by Michael Tweed, introduction by Lawrence Rinder, interview by Bill Berkson and essay by André Padoux

Excerpts

A Silver Lining To All That DarknessBill Berkson interviews Franck André Jamme

✼ ex libris:

What’s going to happen in the next four years? A 1600+ page cautionary tale… Clearly, not enough people are reading anymore.

[...]