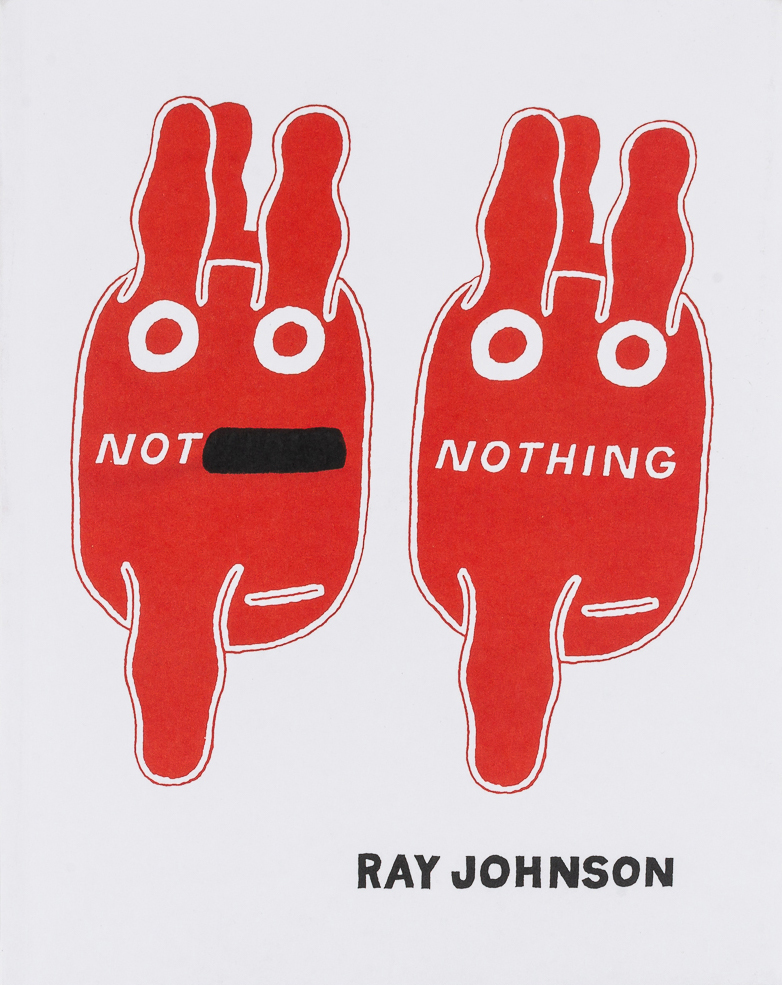

A Ray Johnson Story (excerpt)from Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray JohnsonKevin Killian

excerpts, 04/16/14

Published in Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994, edited by Elizabeth Zuba, Siglio, 2014. All rights reserved. © 2014 Kevin Killian.

I’m backing into Ray Johnson, gingerly, the way I might slide into a bumper car or the driver’s seat of a Lotus, ass first, then swinging my feet to the floor, and only then do my eyes begin to operate as affordance. I’m nervous because, hell, there are hundreds of people who know more about the artist than I, and I’m beyond amazed at what I’ve already read about him; he seems to be the sort of figure that, if you’ve got an inquiring mind, eventually you want to go there and to grapple with him. So I’m here, but not all of me, at any rate not yet. I’m in my lateral stages, so mostly it’s just my butt moving me around, squirming, finding its limit, interpellating the empty space inside, the inside of this document. I have to go easy, go sideways. Almost as if I can’t think about all the geniuses who have written so well about Ray Johnson; I have instead to look myself in the ass and ask myself, do you even know which one he is?

For I used to get them mixed up, Ron Johnson and Ray Johnson. Did Ronald Johnson, the poet (1935–1998), go to Black Mountain too? No, I don’t think he was there, but his boyfriend, the poet and printer Jonathan Williams, acted like Mr. Black Mountain; indeed he wound up publishing The Black Mountain Review. The confusion between two Johnsons may be the sign of a careless mind; I feel the heat, the scabrous accusation of carelessness as I read an interview with curator Paul Schimmel in the Autumn 2013 issue of SFAQ. In it Schimmel waxes wroth about the ignorance of NY-based art writers who “kind of scramble shit up”; speaking of an otherwise “lovely piece” about the artist Paul McCarthy, Schimmel notes that the writer apparently believes that McCarthy, Bruce Nauman, Chris Burden and Mike Kelley were all of the same generation. “I’m reading this shit and I’m going, This is just bullshit. This person doesn’t know anything about the truth.”1

So I’m aware of the dangers and yet I wade into this river with blinders off—the river of imagining a Ray Johnson under the influence of Ron Johnson (as T. S. Eliot famously posited a Seneca under the influence of Shakespeare), and vice versa, the fantasy in fact that they were, if not the same person, interchangeable up to a certain point, at the point in which fine discrimination begins. I follow the lead here of performance theorist José Esteban Muñoz, whose 2009 book Cruising Utopia fancifully conflates Ray Johnson and the art writer and activist Jill Johnston (1929–2010, thus still alive when Muñoz published his book). “I transport Johnston and Johnson from their historical perch and attempt to understand them alongside each other, as well as in the historical moment that enabled their projects. The project here is to understand how this work represents a much larger communal vibe, not to cast the two cultural producers as some kind of individualistic heroes.”2 Unless you can see the similarities, you can’t then parse them out and tell what makes Ray Johnson so special. Nor can you spot the historical moment in the massive sack of Ray Johnson’s eccentricities, it’s like a needle in a haystack of charm and something sort of like slapstick. That I think is half the reason people like this work, and maybe it prevents us from seeing something else about it, something fogged up by the smile on the face of meaning.

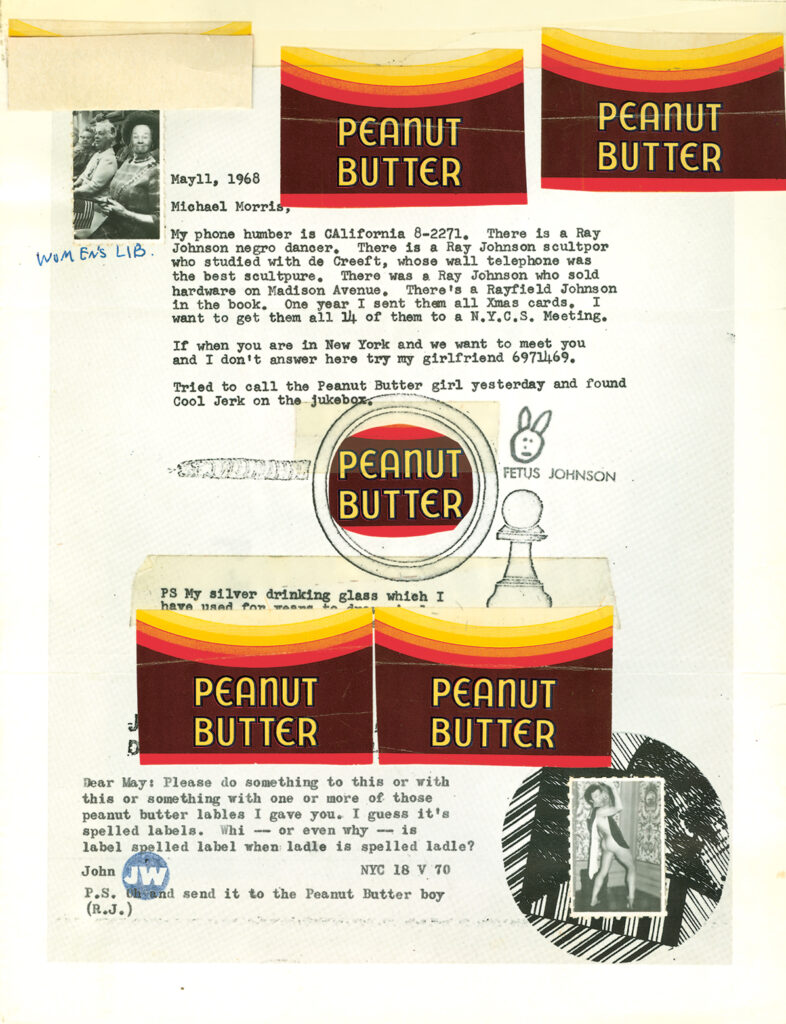

So I ask myself, why does my mind confuse Ray and Ron Johnson? First off it’s their Johnson-ness… “Johnson” may be the second most popular surname in the U.S.—just below Smith—but still, there they were stuck with the name, and both at the height of their powers when Lyndon Johnson prolonged the war in Vietnam, making it perhaps the most despised name in the world. Did this disparagement of Johnson disturb either one of our guys? Robert Duncan, in “Passages 25: Uprising,” was writing, “this black bile of old evils arisen anew,/ takes over the vanity of Johnson;/ and the very glint of Satan’s eyes from the pit of the hell of America’s unacknowledged, unrepented crimes that I saw in Goldwater’s eyes/ now shines from the eyes of the President/ in the swollen head of the nation.”3 The usage of “Johnson” to mean “penis” you don’t see much in this book, but otherwise Johnson makes every other joke in the world about his name. He tells Michael Morris (plate 73) that he’s located fourteen Ray Johnsons, once sent all of them Christmas cards, plans to invite them to a meeting of the NYCS. My mother used to say that if you meet someone with your own name, he was your doppelgänger, and that one of you would die before the year was out—old Irish folk wisdom of haunted woodlands and blood-stained sea cliffs. Tempting fate was Ray Johnson’s métier, I’m thinking. (We see him sign the name “Ray Charles” on one letter, perhaps trying out blackness—or blindness—or perhaps only trying to avoid his Johnson-ness?)

Plate 73 from Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994. All rights reserved. Image courtesy of Richard L. Feigen & Co.

Secondly, it’s their gayness. Asked about his invention of the “Nothing,” which the interrogator describes as “something like a closet happening,” Ray Johnson replies, “Open a closet door close a closet door” (plate 15). He’s vatic often enough, but chiefly when he speaks in the code of gay men in mid-century. What Eve Sedgwick called the “epistemology of the closet” constituted pretty much the chief form of artistic expression in December 1963. Ron Johnson spoke often of the difficulty of putting his masterwork, ARK, out there into a realm in which so many other great practitioners, Olson, Zukofsky, W. C. Williams, Pound, etc., were so resolutely heteronormative—the cult of the big straight man.

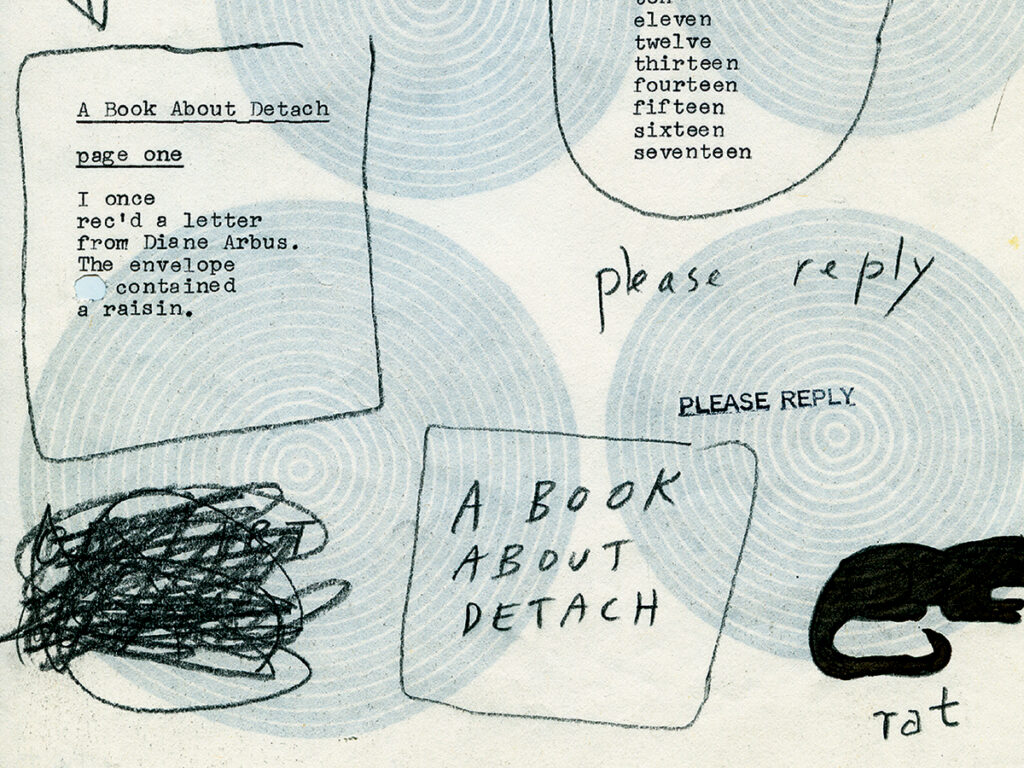

Could we further agree that both Ron and Ray worked within the general imaginary of the subaltern position, the consciousness of being judged as something other than top-notch? Okay, we all of us feel that others are getting the breaks we deserve, but Johnson & Johnson really used it in their practices to interrogate the nature of hierarchy in a time of American expansion and self-confidence. For all his acclaim, Ron Johnson was rarely in print, and his status as a “poet’s poet” was exactly the sort of formation the cognoscenti dreamed up as a pleasant way to articulate “loser” status. It comes with heaping doses of pity and condescension. As for Ray Johnson, well, if he wasn’t in the shadow of Johns and Rauschenberg, then he was like an also-ran Warhol or even a third-rate sort of Yoko Ono. How many times can you be described as “America’s best-known unknown artist” before you start feeling the burn, the humiliation? And in his writing and his art Ray Johnson uses underdog status as efficiently and aptly as, say, Rodney Dangerfield. “I don’t get no respect.” At the bottom of his letter to Michael Morris (plate 73) he leaves the rubber stamp mark of the pawn—apt symbol for the rank and file of the art world.

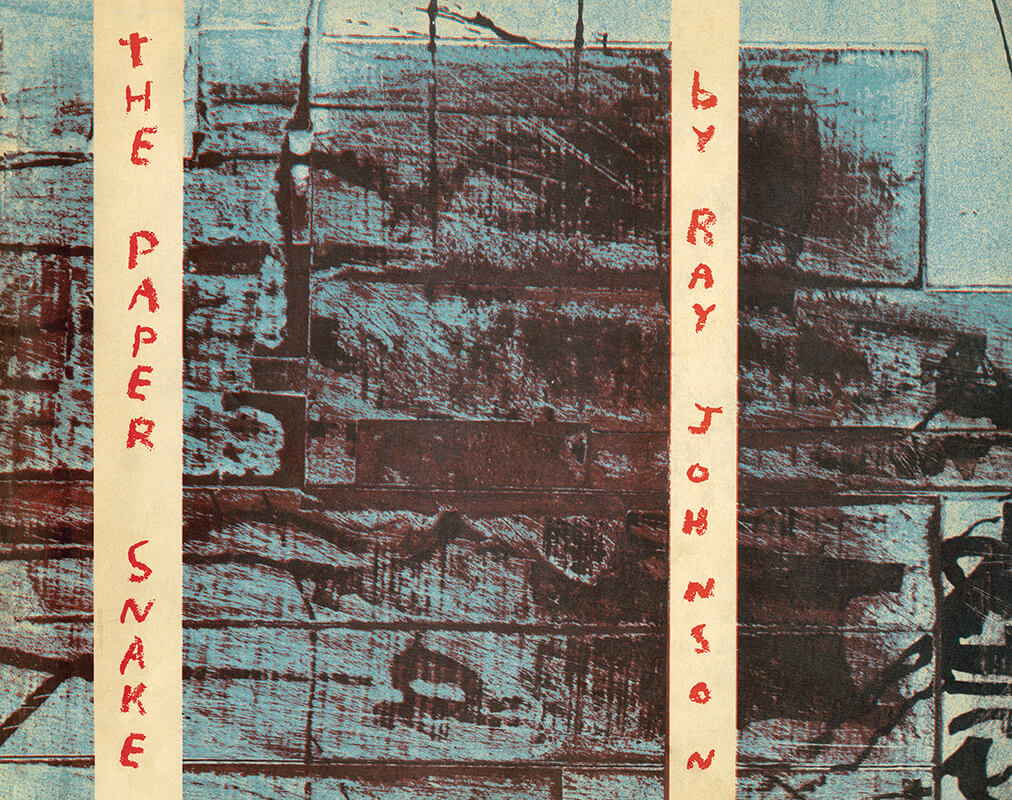

And beyond a common status, RJ and RJ further shared a method, at least the way I’m reading them, and that would be the curtailment they practiced. Ronald Johnson published RADI OS in 1977, practicing erasure on an old volume of PARADISE LOST so that only RADI OS remained from Milton’s title. In Ray Johnson, how many times do you see the final words of his sentences, speeches, questions, adumbrated by white space or by the rumble of a new thought. “Dear Dick,” he writes, in The Paper Snake, “I enclose a Lucky Strike. … I do not enclose Lucky Str.” It was an extreme telegraphese that anticipates the text message shorthand of today, and as such, an unexpected affirmation of existing intimacy, almost of telepathy, as he who might no longer have to explain, you know me so well you even know what I’m about to say, we don’t have to spell it out.

The essay can be read in its entirety in Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994.

footnotes

- Quoted in Charles Desmarais, “Interview with Paul Schimmel,” San Francisco Arts Quarterly 14: 53.

- José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press), 116.

- Robert Duncan, Selected Poems, edited by Robert J. Bertholf (New York: New Directions, 1997), 118.

see also

✼ consideration:

“Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera … achieves the hidden aim of all postmodern work. Namely, befuddling the reader with the dilemma: is this sheer brilliance? Or merely incomprehensible nonsense?”

[...]