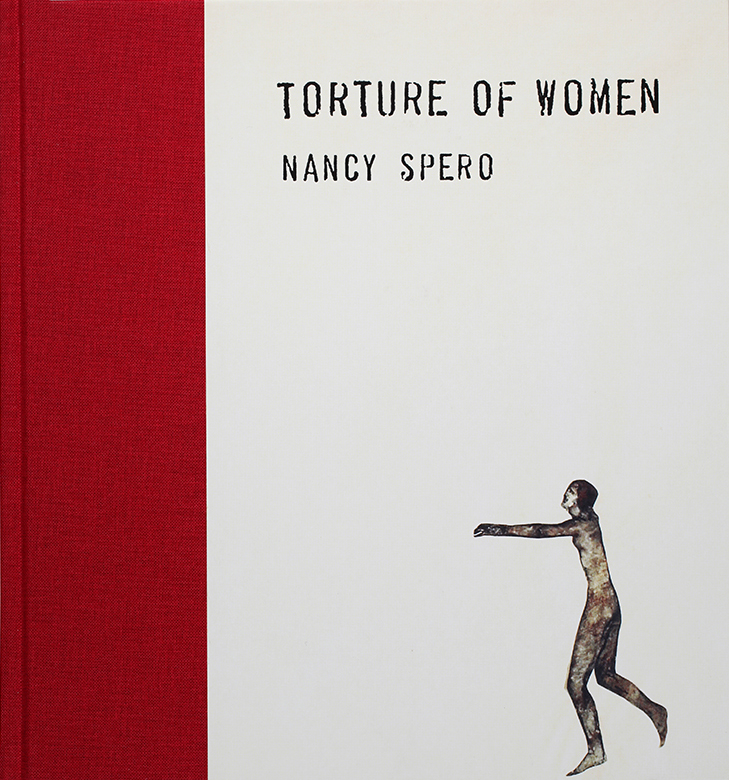

Fourteen Meditations on Torture of Women by Nancy SperoEssay by Diana Nemiroff

excerpts, 09/24/10

Published in Torture of Women by Nancy Spero, Siglio Press, 2010. Originally published in Nancy Spero: Weighing the Heart Against a Feather of Truth, Xunta de Galicia, 2005. Copyright © 2009 the author. All rights reserved.

PANEL I

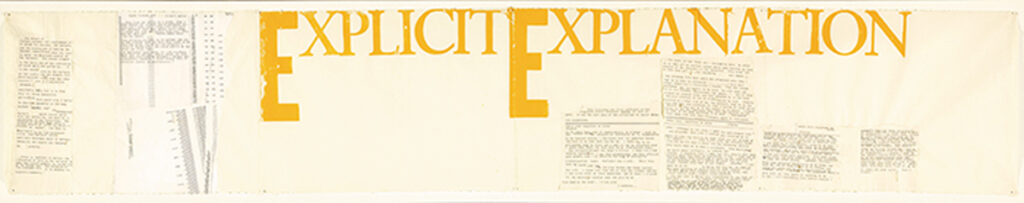

With the words “Explicit Explanation,” hand-printed in large yellow letters that distantly evoke the embellished lettering of a medieval illuminated manuscript, Nancy Spero opens Torture of Women, a monumental work of protest that took her two years to complete. The words, which dominate the first panel, are drawn from the Commentary on the Apocalypse, compiled in the 8th century by the Spanish monk Beatus of Liébana. Beatus’ Commentary is structured as a sequence of Storiae depicting the end of the world and the Last Judgment; each is accompanied by a lengthy text, the Explanatio, which interpreted the fearsome images. Spero knew one of the medieval copies of the Beatus Apocalypse and it clearly offers a model for the visually expressive interrelationship of text and image in Torture of Women.1 But equally important, the Apocalypse provides the first of several metaphors drawn from the ancient world that Spero will employ throughout the work. Woven through contemporary documents witnessing the practice of torture as an instrument of political control, they provide the poetic structure of the work, giving it universal significance.

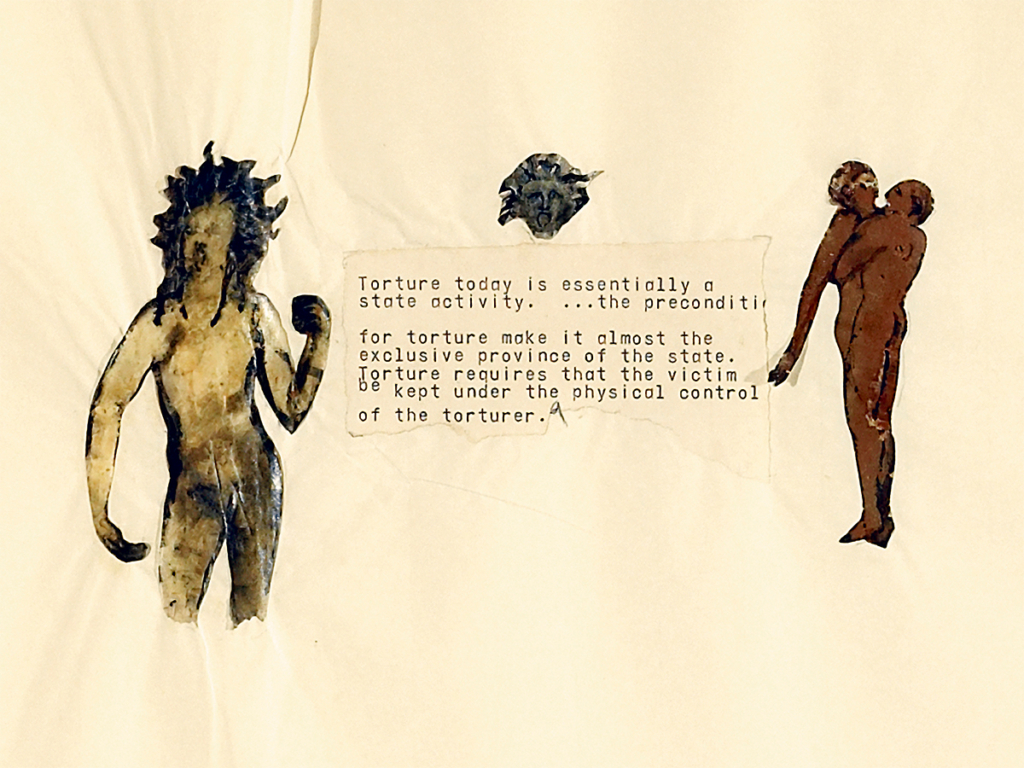

It is difficult to speak about torture and even harder to represent it. Apart from those who have experienced torture personally and those dedicated to eradicating it, most of us fail to understand the meaning of torture because we find the reality too unbearable to contemplate. How to make the obscenity of torture visible without becoming obscene is the paradox Spero must address, and thus it is text that serves both as a vehicle of communication and a visual presence in this work, while figurative images are scarce. Only once, in a small vignette of an interrogation in the third panel, do we see the essential pair of any torture situation: the unequal confrontation of the torturer, cloaked in the magistrate’s robes of authority, and the defenseless victim. Spero’s visual reticence is telling. Whereas at various times in the past torture was an acknowledged weapon in the judicial arsenal of the state, today numerous international conventions forbid it. Torture now is hidden, officially denied, invisible.2 The tortured have become the disappeared. The absence of explicit images in Torture of Women echoes this disappearance. Instead, Spero’s visual imagery functions on a symbolic plane: her snakes, dragons, and winged insect-like creatures are the monsters that emerge when reason sleeps, while tiny, dismembered heads with mouths open in horror keep watch.

The role of text in this work is to bring torture into the open, ruining its invisibility. While her images preserve the ambiguity of the nightmare world to which they belong, the documentary texts that Spero has compiled, noting the source of each one, are intended to shed light on the purposes, methods, and experience of torture, and in particular the torture of women, from its primordial origins in the power struggles of the gods to its use as a tool of political control in the unstable regimes of the developing world today. Most are reports by witnesses or accounts by the victims themselves of the inhuman treatment they suffered. Some, however, are analytical in nature, such as the definition of torture taken from Amnesty International’s 1975 Report on Torture with which the first panel begins:

The nature of torture assumes the involvement of at least two persons, the torturer and the victim, and it carries the further implication that the victim is under the physical control of the torturer. The second element is the basic one of the infliction of acute pain and suffering. It is the means used by the torturer on the victim and the element that distinguishes him from the interrogator. Pain is a subjective concept, internally felt, but is no less real for being subjective. Definitions that would limit torture to physical assaults on the body exclude “mental” and “psychological” torture which … causes acute pain and suffering, and must be incorporated in any definition. The concept of torture does imply a strong degree of suffering which is “severe” or “acute.” One blow is considered by most to be “ill-treatment” rather than “torture,” while continued beatings over 48 hours would be “torture.” Intensity and degree are factors to be considered in judging. …

There is implicit in … torture the infliction of pain … by the torturer, to make the victim submit, to “break him” or to “break her.” The breaking of the victim’s will is … to destroy the victim’s humanity.3

Compared to the Codex Artaud, in which language is fractured to the point of incomprehensibility and the layering and overlapping of the quoted excerpts of his writing makes reading difficult, Torture of Women is relatively legible. Not only do its texts constitute, collectively, an “explicit explanation” of torture, but its book-like nature is emphasized structurally by the linear sequence of the panels from left to right, and by the use of mechanical means of writing, such as letterpress and the bulletin typewriter. At the same time, Torture of Women surpasses the book by reason of its public scale and its material presence. We see this in the way the violence of the content is reflected in the distressed surfaces of the torn fragments of text Spero has pasted onto the paper of the panels, in the gaps and irregularities in her typing, and in the uneven pressure of the hand printing, all of which give the communications a quality of physical immediacy and urgency.

footnotes

- In an interview published in Margit Rowell, ed., Antonin Artaud: Works on Paper (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 138, Spero mentions an essay that her husband, the painter Leon Golub, wrote in the late 1950s comparing Picasso’s Guernica with images from the Beatus Apocalypse of Saint-Sever, and recalls her fascination with the book: “We poured over this book, this beautiful, fantastic, ferocious Apocalypse, with animals drowning, their tongues extended. I had tongues sticking out in the late fifties works, the ‘fuck you’ paintings, predecessors of the War Series and Artaud.” Golub’s essay, “Guernica, the Apocalypse of Saint-Sever,” may be found in Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Leon Golub: Do Paintings Bite? Selected Texts 1948–1996, (Ostfildern: Cantz, 1997), 184–191.

- This essay was written early in 2004, before the reports of abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad and at Guantanamo Bay came to light. Although the U.S. ratified the UN’s 1984 Convention Against Torture and the Third Geneva Convention concerning the treatment of prisoners of war, the Bush administration’s insistence that detainees held at Guantanamo were “enemy combatants” rather than prisoners of war permitted a gray zone to open up around the use of torture. Arguments that torture and inhumane treatment should be permissible weapons in the “war against terror” have brought torture once again out into the open and made silence impossible.

- Amnesty International, Report on Torture (New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 1975), 34. Spero has shortened the original text somewhat and altered the language slightly to make it gender-neutral.

see also

✼ the improbable:

A miscellany of investigations, rants, manifestos, meditations, studies, lists, questionnaires, film scripts, and more in Issue 1, No. 1 Time Indefinite. A few excerpts her and there.

[...]