Making The Hand Obey Another’s PsychologyRobert Seydel interviewed by Savina Velkova

excerpts, 04/02/14

This interview by Savina Velkova was conducted with Robert Seydel in 2010. It is is the only interview with Seydel before his sudden and unexpected death in January 2011. It reveals much about an artist whose own life and those of the personas he constructed were knitted in inextricable ways.

It was included in A Picture Is Always a Book: Further Writings from Book of Ruth, edited by Lisa Pearson, Siglio, 2014. All rights reserved. © 2014 Savina Velkova, the Estate of Robert Seydel and Siglio Press.

Savina Velkova

How did Book of Ruth evolve?

Robert Seydel

It was originally called The Book of Saul, which remained the case even after Siglio published the pamphlet 5 Hares & 3 Ruths in 2009 in its Ephemera series. I began working on the book in about 2000, starting in part with a conception out of Duchamp—his Bride and Bachelors. Ruth was the Virgin or Bride, and Sol, Joseph, and Marcel the Bachelors that surrounded her. Central from the start I think was the kernel of two small letters—RS: Rose Selavy, Ruth and Sol, me, my mother Rita Seydel. It was a kind of combinatory thing, based in initials and the shiftiness of gender and identity. Even now the spelling of Sol’s name wavers between his given name, Sol, from Soloman, and Saul. And in Ruth’s journals her “I” can’t seem to focus itself—she wavers, sometimes capitalizing it and sometimes typing it lower-case.

Ruth was always going to be the artist, but Sol was more important at first. There were his notes on the history of plumbing, his invention of a Hall of Scatology—a kind of honor roll of underground men, and a series of writings, recollections of house calls as a plumber for instance. My father, when he was a kid, used to sometimes accompany Sol on his rounds. He’s talked about fitting pipes with him and driving around Brooklyn and later around Queens. The idea at first was historical fantasy. I wrote in an early work (in which) Saul’s interests were responsible in fact for Duchamp’s statement regarding his urinal or Fountain in his unsigned editorial “The Richard Mutt Case,” published in the magazine The Blind Man, in which he said, “The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.” Saul’s tutelage in the book led, retrospectively, to Duchamp’s interest in plumbing and American ingenuity in water fixtures (as well as his invention of a “ministry of gravity”).

Remnants of all this remain in the book. There’s the collage for example titled “Blind Saul,” a reference in part to the magazine The Blind Man. And Sol remains an underground man and blind in a sense, like a mole, which is one of his animal familiars. Did the Great War and what he witnessed in the French forests do that to him, or was it inevitable, his going underground and his quietness? He wasn’t demonstrative as a person in any way, but there are stories about how much he came to hate the Red Cross, which made the wounded in hospital, as he was, pay for toothpaste and toothbrushes. It’s kind of legendary in our family, his hatred for the Red Cross. To this day certain members of my family refuse to make donations to that outfit as a result. The red cross, which is such a prominent sign in Joseph Beuys’s work, plays a role throughout Sol’s material. But the point is that Ruth fairly quickly took over, which makes sense. She’s an artist, and I still haven’t figured out how to make Sol’s materials—who’s not—into work. I can’t find form for them. I’m still planning to do a Saul book, but at present it’s stalled, maybe interminably.

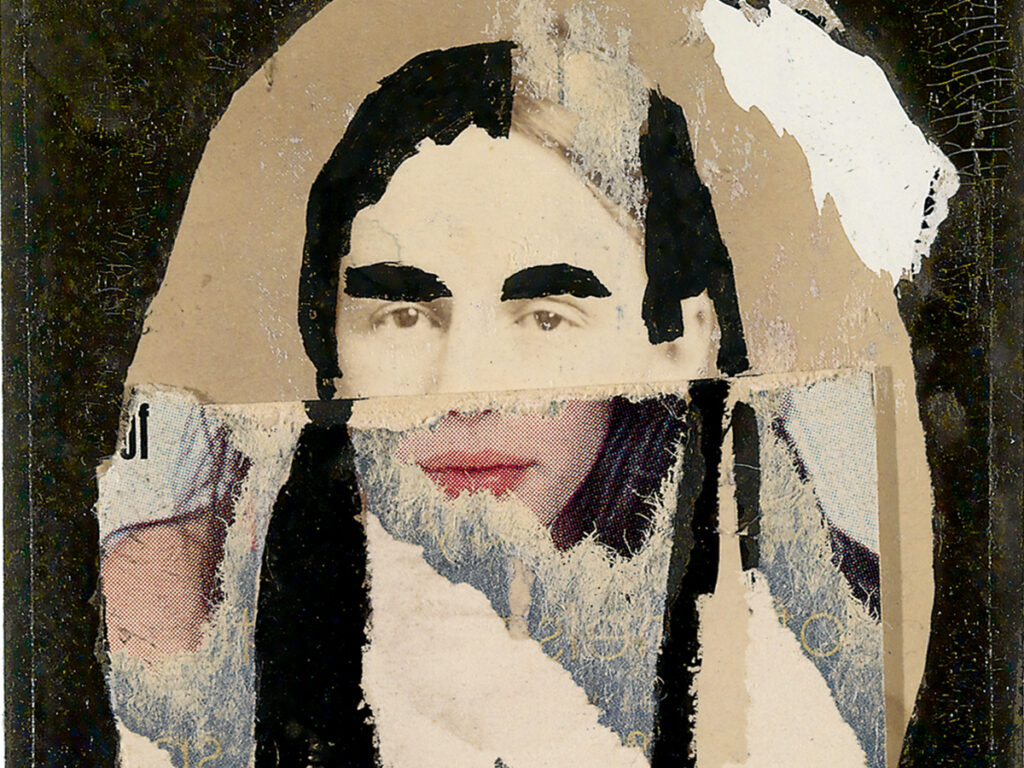

But in the end I’ve come to care more about Ruth—we share more things, and I can speak in her voice and sometimes I don’t know whether it’s me speaking or if she is. It can get confusing—I’ll be looking through my notebooks and have to figure out if something I’ve written is Ruth’s or if it’s something else. That happens with the collages too. Things twist up with her, I’m more entangled in her possibilities and dilemmas, I have a harder time distinguishing between us.

SV

What was your work process like? Were certain pieces created before the idea for the book was born?

RS

It happened and still happens simultaneously. Again, Sol’s writings came first, and were really some of the first things I did. Ruth’s writings began a little later, and again took over—I think the point is that Ruth, being an artist, is easier for me to access or to submerge myself in, despite the shift in gender. She became closer to me, in attitude, style, her relation to the world. But in terms of priority, collages or journals, there isn’t any. And the narrative, such as it is, is a pretty loose construct—it makes itself up as it goes along. It’s pretty simple—if I make a trip to New Mexico to visit my sister, for example, that might become something Ruth and Sol do. In part it’s a kind of parallel life. I use what I have and do to fashion who Ruth is. As another instance, I’m pretty involved in thinking about and looking at what’s referred to as the “Animal Style” in art—from Native American pictographs and the history of Paleolithic stone art to, say, Henri Michaux and Dubuffet and Bill Traylor. So that becomes an aspect of Ruth as well.

SV

How much of your aunt is in the character of Ruth? What motivated the creation?

RS

Ruth’s pretty much a complete fabrication, but she’s based on a set of supports that were real in my aunt’s life—being a bank teller, volunteering for Hadassah, being an amateur painter. She taught every one of the kids in our extended family, which was pretty small actually, how to paint. For me, that was on Sundays, when we drove in to visit. I was the youngest of that generation and like to say that her lessons never stuck very well. It’s true; whereas my cousin Barbara Goldberg, who Ruth also taught, is an accomplished artist, my own skills are pretty rudimentary so far as drawing and painting are concerned. Being the youngest, I imagine now that her patience had worn thin, but more likely I wasn’t that interested. What I remember most from those visits was the smell in the apartment, a sense of their age. It’s one reason I think the image of dust is so important—Ruth kept their apartment immaculate, but what I recall is a kind of atmosphere. Maybe they meant mortality to me—one of my first experiences of what age was.

On the other hand, sometimes I think my inhabitation of Ruth is based in childhood jealousy, which doesn’t seem that far-fetched to me. When my sister was a teenager, she lived with Ruth and Sol in Queens for a few years, or for some time anyway, and slept with Ruth in the one bedroom in the apartment (Sol slept on the roll-out couch in the living room, which in the book also serves as Ruth’s studio, such as it is). My sister had been accepted to the High School for Performing Arts in New York—she was a dancer, but you had to live in one of the five boroughs and we didn’t, we lived out on Long Island. So she claimed residency with Ruth and Sol and for a while only came home on weekends. I guess I would have been about six, seven, eight years old at the time. Anyway, she lived with my aunt and uncle and studied art in their proximity, and now in turn I live with them, by proxy—that’s one way, it’s occurred to me, if perhaps a fantastic one, to think about what motivates the book.

SV

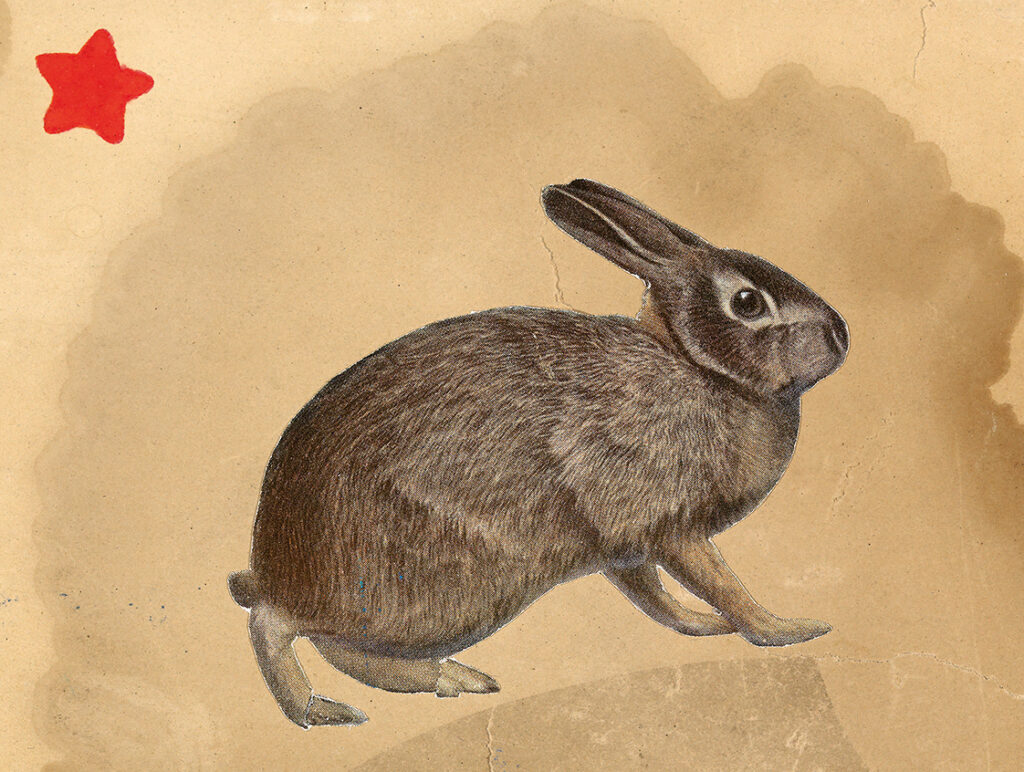

Did Ruth’s original piece (Untitled [Doe]) serve as inspiration?

RS

No, I love that piece, and along with the frontispiece photograph, it’s the only authentic thing in the book, but it’s just one of the two or three paintings by Ruth still in my possession. My sister also has a few of Ruth’s paintings, as do my cousins. At one point I thought, like Asger Jorn, that I would use what I do have of her paintings as material for her work, collage into them, over-paint and add objects to them. But I haven’t been able to bring myself to do that, at least not yet.

But the Doe just happens to be one of my favorite paintings by Ruth, and it’s odd, it isn’t really very characteristic—most of her pictures were made by copying photographs of flower arrangements or street scenes in Paris, there’s very few animals. But that’s not strictly true, there are some pictures of cats, and she always owned a cat, which she also does in the book. And she also made scrapbooks for the kids, full of funky collages and really terribly saccharine and sentimental pictures, among which cats figured prominently. But while the Doe is an anomaly, I share with it a certain sensibility, so I put it in the book.

SV

What role did Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp play in your development as an artist?

RS

Both of them are important to me. Cornell was crucial in fact, opening me to possibilities that I didn’t altogether realize until I came to him and looked at him seriously—the idea of collage as a total way of working, and of magic and combinatory art. But in terms of Ruth, both Cornell and Duchamp are really just ciphers—they don’t exist except as functions of a sort in Ruth’s mind. They’re a fantasy, or a space for loneliness and the unrequited to reside in or focus upon. Cornell is for Ruth what Bacall or Toumarova were for Cornell—desired distances. So maybe in that sense he’s an even bigger influence than I realize or would like to admit. Ruth sends objects and missals and valentines of sorts to Cornell just as he sent his to Dietrich or his ballerinas.

But a number of other artists have been as important to me as Cornell and Duchamp. Wallace Berman and Ray Johnson and Tom Phillips come first to mind. And above all William Blake. I can remember saying to myself, in the way one does when one’s trying to figure out what you want or need to be doing, that my goal was to found a way to make visual art into a form of literature, with the kind of density I associated with my favorite writers.

I think both Cornell and Duchamp are situated within that kind of territory. Duchamp’s notes for “The Bride Stripped Bare” is a great long poem, opaque and strange but wild and rich in its language and playful. I wouldn’t know how else to describe it but as a long poem including pictures, in the way that Pound said an epic is a long poem including history. Ruth is, I hope, in that kind of space, somewhere between the literary and visual arts. When I was about fourteen or maybe fifteen, Kenneth Patchen was the first artist-writer I came to, and for me he remains a beautiful figure.

But, like Cornell again, writers have been more important to me than artists; Emily Dickinson and Gertrude Stein are preeminent, both for Ruth and for myself. In a sense, Ruth has been a way to back into writing, a way to enter into writing from the outside. That one does that through the voice of an unknown woman may have some meaning larger than I’m prepared to acknowledge. Cornell is Ruth’s Master in the book, and sometimes I think of Dickinson’s so-called “Master Letters” in relation to Ruth and her relation to the world.

SV

Where does the impetus to access and speak through a persona come from?

RS

Speaking through another’s voice is hardly an original tactic, though I suppose to some degree it is in the visual arts. “I is another,” Rimbaud said, lodging uncanniness at the heart of what we are. From Browning to Pound to Pessoa, speaking in voices was a way to carry history and multiplicity into the poem. Armand Schwerner asked, as a poet, “Why leave fictive experiments to the prose writers?” I guess I’ve asked that myself, but as an artist. To attempt to make the hand obey another’s psychology, at least so far as you imagine it, doesn’t seem that different to me than fashioning the voice of a literary character.

And art has always seemed to me a kind of exit out of the self, a way to get beyond the self. I don’t think I’ve ever really understood why “self-expression” is an attractive motivation for making art, which is how students so often speak about what they’re doing. Who cares really? But to fashion a self, that seems to me another thing. Walt Whitman isn’t only that boy “starting out from Paumonak,” but “Walt Whitman, a kosmos”—that is, an invention. The artist’s job, according to both Robert Henri and Jasper Johns, is to invent himself. So that’s made explicit here, as a kind of a primary endeavor. The point is revelation and an opening outwards, an expansion into the air of art itself. I think Ruth is a kind of vehicle for that. And Ruth herself often feels a voice entering her from the outside, as if she was a conduit for something other than herself. “My name is Ruth?” she asks at one point, surprised by her own pronoun.

SV

Where does she take you that you wouldn’t be able to go on your own?

RS

I remember that in a college writing class I wrote a journal that was full of lies and exaggerations—I thought then, my life’s boring; I was depressed, so I made up a life full of incidents, a life that was more interesting than the one I was leading, or at least one that I thought was more interesting. Acting was never an option for me, but I became in that journal a dramatist. It was a kind of myth-making endeavor, founding a larger possibility of self. Sleight of hand, sidestepping and indirection are important strategies for me. It’s related to Dickinson’s thing: “Tell all the Truth, but tell it slant.” Ruth’s a way to open art to something else, and to tell the mind’s contents as if they were coming from a long way off. She allows me to access states otherwise inaccessible to me. Her mind and hand are my own, but amplified. And “slanted.” Her history, the time in which she lived, my imagination of Queens—these things open my work to other contents, and hopefully as well to an instance of fuller life.

The odd thing is that nothing ever really happens in Ruth’s life either. She goes from the bank to the butcher to her apartment; otherwise, she lives wholly in her imagination. The only events that matter for her are the signs and messages coming from the Imagination, which she generally capitalizes—seeing horses, for instance, emerge in the steam escaping from manhole covers. I’ve come full circle in that sense, inventing a life as boring and constrained as I thought mine was back when I was a student in college. Silly, isn’t it? You’d think you’d want to invent a heroine with some tooth to her…

But there’s been a number of characters in my work besides Ruth, beginning with an early abandoned figure named R. Welch, who was a researcher in charismatic quotients, which he applied a mathematical formula to. Welch already contained in embryo a shift in gender identity, in that his name was derived from Raquel Welch. In fact, he understood their sharing of surname as prophetic of his scholarly research into charisma, which of course she had in spades. So he made an appointment to interview her, which didn’t go very well. As for Ruth, perhaps it was simply a challenge—could I be believable as a woman artist? That’s always been a question for me, but particularly early on. Now it’s mostly not an issue—she’s so taken over part of my art-making function that I don’t really question her authenticity anymore. I thought originally I wanted to inhabit another person; now she inhabits me.

SV

Your connection to Ruth is complicated by the fact that she is a woman. What is the productive function of this contradiction for you?

RS

Well, I love artists who contain a mixed pedigree, or who are contaminated in some way, who contain contradictory impulses. And I’m particularly drawn to an image of the artist as non-professional or anti-professional, outside the sphere of trade and the economies of art and product, which is a word I hate as applied to art. Ruth kind of begins in that place—she says, for instance, “The galleries are made for fashion. Nothing I make is.” In a journal text not reproduced in the book she expresses jealousy about Cornell’s gallery representation and goes to visit Julien Levy, who rebuffs her (although that’s mostly in her own mind). But her desire nevertheless to do that is symptomatic of her conflicted nature: she works in a bank but hates money, and while her art remains deeply private, she associates herself or otherwise insinuates herself into the lives of two relatively famous and public artists. Such dilemmas are partly my own, but they also seem centrally a woman’s and particularly a woman artist’s during the fifties and sixties.

I understand Ruth’s status as a woman and a type of artist outside the mainstream as a kind of double-whammy here. Even Cornell, who in a sense is a domestic artist himself, doesn’t take her seriously. They share care-taking roles, Ruth as regards Sol and Joseph as regards his brother Robert (who in a mostly invisible way is a stand-in for myself). And they’re both located in the boroughs, beyond, let’s say, the corridors of power, which lack is also evident perhaps in the choice of materials—detritus, garbage, street-sweepings—that they use to make their art. But, while sharing these things, Ruth’s a woman and Joseph isn’t. She’s more distant and further along the line of powerlessness than he is, which is a condition and maybe even an ethical stance that I’m interested in, in league for example with someone like Robert Walser. Ruth’s distance from power and her status as a private or amateur artist, just as much but in part related to her being a woman, is what I think attracted me to her possibilities in the first place.

And that privacy, her being an artist so to speak without portfolio, allows me a certain latitude and freedom to examine my own dilemmas as related to art—public speech versus private content, insularity and a propensity for withdrawal versus love and care for art writ large. As well, Ruth, in a perhaps bizarre way, allows me to talk to myself, to listen to what I’m thinking as if from the outside. Art, to accommodate reflection on itself, needs indirection and distancing. I don’t know that I could have written something like the “Formulas” in my own voice—it needed Ruth as its presumptive author. I can lodge my idiosyncrasies and romanticism in her in a way I wouldn’t altogether know how to do otherwise.

SV

And, to go beyond Ruth’s circumstance as a woman artist, what draws you to the female consciousness in terms of artistic capabilities, form and mentality?

RS

There’s both a quickness and interiority as well as verbal abundance in the women artists and writers I admire that I think is different in kind from men, and I’ve tried to access that as best as I know how to. To catch the mind in flight is one way to describe what I mean—Joanne Kyger, who is obliquely named in one of Ruth’s journal texts, is one example of this speed and informality, which has a kind of power associated with dailiness and the mind’s capacities to both hold and celebrate it. The other quality I’m after, which I think women writers in particular embody, and which in an almost paradoxical way is related to this idea of quickness, is a type of chiseling of language, as in the poems of Dickinson and Lorine Nediecker and even Stein in her idiosyncratic way. Ruth tends both ways, as I do generally—towards interior verbal excess and also towards a sometimes sharp and sculpted rhetoric, at once oblique and specific. This swaying between approaches is apparent, or at least I think it’s apparent, in the visual work as well, from a clogged and thick kind of a collage structure to a quicker, less dense picturing.

So in a sense taking on the voice of a woman has meant accommodating and attempting to take possession of certain ways of working for myself, ways that I think were already apparent in my art-making prior to coming to Ruth. But, to use this word again, these approaches were amplified and extended by my effort to work through her. And in a number of ways my first models for what an artist was came from the women in my family. My mother wasn’t really an artist, though she did paint for a while and she played the violin, but her delicacy and her profound care for rightness in the world were certainly associated in my mind with the idea of the artist when I was young, or so I imagine it now. It’s no accident that the book rides on and contains her name. My mother and Ruth were in a sense my first teachers in art. But while it’s Ruth’s book, it’s dedicated to my mother. She stands I think as its invisible center, which feels right and somehow predetermined. The tangle backwards to the location of art and its importance as an activity is centrally through women for me

see also

Affinities

“The Rabbits are in the Stars”Following the Hare in Robert Seydel’s Notebooks

Events

Robert Seydel: The Eye in Matter Queens Museum, July 19–September 27, 2015Curated by Peter Gizzi, Richard Kraft and Lisa Pearson

Affinities

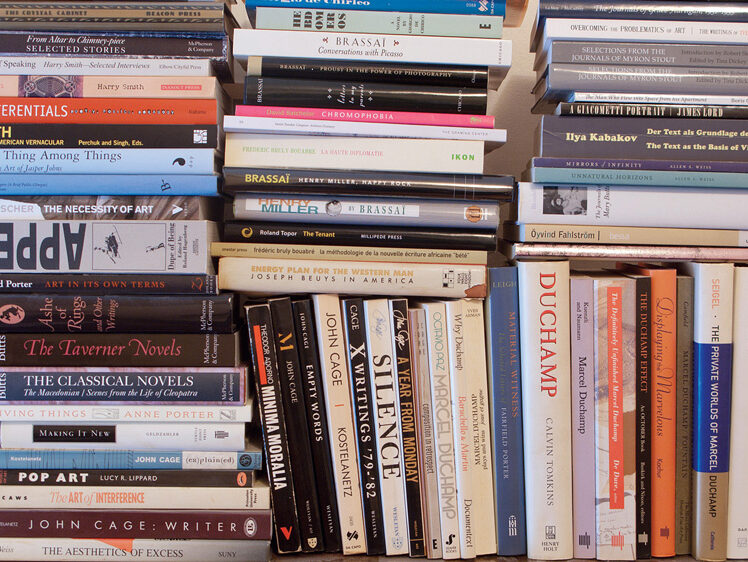

Arranging One’s Books, No. 2 Robert Seydel’s library and a reading listPhotographs by Richard Kraft

Affinities

On the Art of Robert Seydel and the Construction of “Ruth”Lisa Pearson

✼ elsewhere:

“How do you know where the boundaries of a life are? How do you know where to stop? Or when something doesn’t apply?” —Nicole Rudick in conversation with Sam Stephenson at AIR/LIGHT

[...]