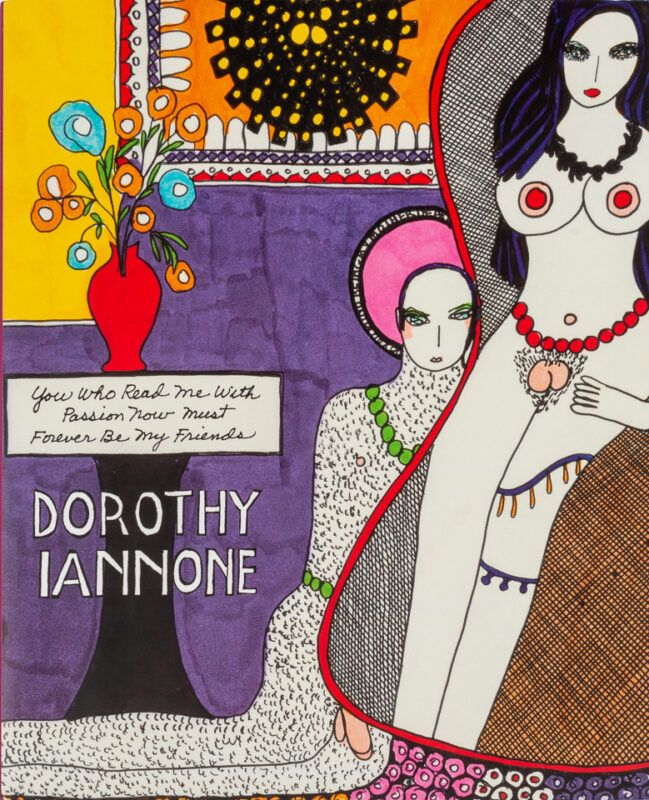

Editor’s Afterword to It Is Almost ThatA Collection of Image+Text Works by Women Artists & WritersLisa Pearson

excerpts, 12/09/11

Published in It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers, edited by Lisa Pearson. All rights reserved. © 2011 Lisa Pearson and Siglio Press.

Remember how starry it arrives the hope of another idiom, beheld

that blush of inexactitude, and the furor, it

will return to you, flotsam blocked out.

—Barbara Guest

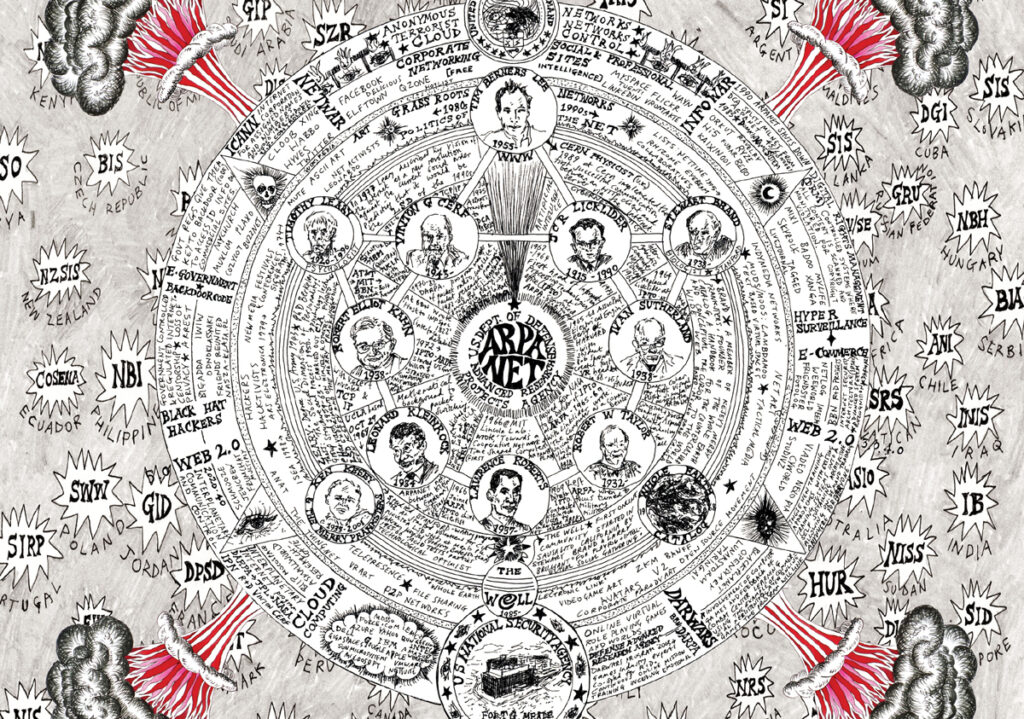

It is almost that evokes the humming state of the not-quite-this-and-not-quite-that, a state that conjures an awareness of what accepted categories cannot contain, what familiar taxonomies cannot order, what one medium cannot express, what a single language cannot circumscribe. It is something, in other words, that can never be just that — fully one thing or another, wholly belonging here or there: something then mutable, indeterminate, ineffable. And the phrase it is almost that, in its indeterminacy, signals the many things something may or may not be — and may or may not become — simultaneously. It is almost that points to the inverse of lack — to boundlessness.

It is almost that is a phrase from Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s eponymous work included in this collection. She uses it to set a syntactical inquiry into motion in which relationships are constantly shifting and small white letters momentarily hold inscrutable fields of black. I use it as if to chart a constellation, selecting a discrete number of stars from the infinite field of the night sky, connecting them in unpredictable ways, in order to see something that might not otherwise be seen. It is almost that titles this collection not only to invoke the resistance to categorization and accepted order, but also to acknowledge the expanse, the limitless possibility of what one might still see: look at the sky again and, by force of imagination and concentration, another constellation emerges.

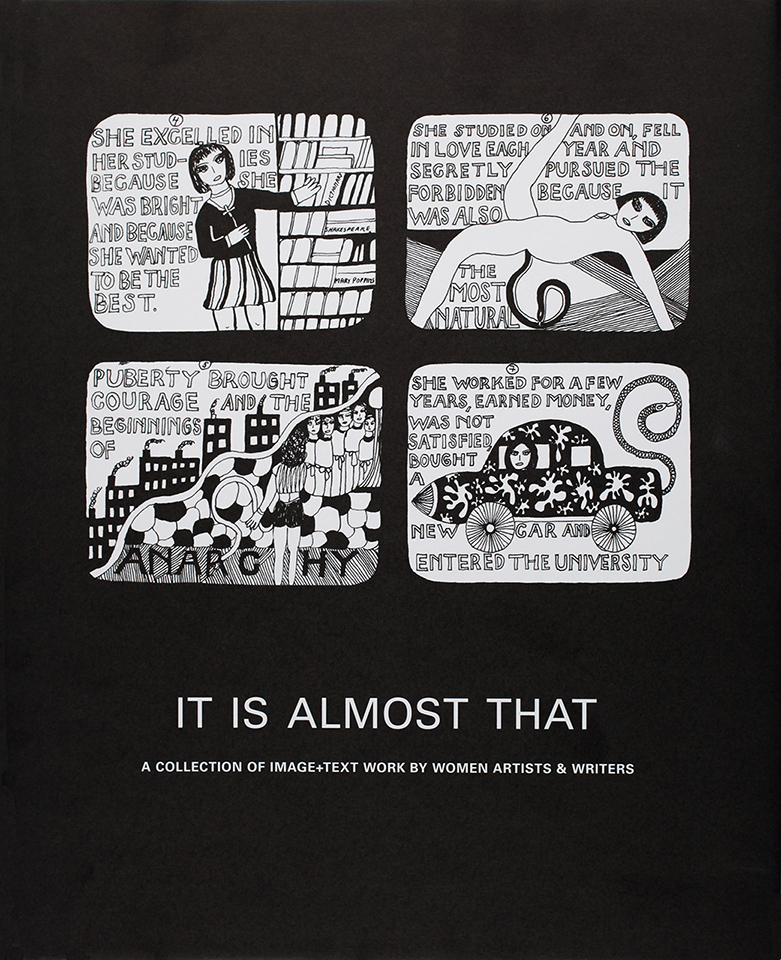

In their unique use of image and text, in their own expansion of the given conventions and paradigms, the individual works included in this collection live in both the visual and the literary. But they are works that are often relegated to a single world — art or literature — and thus they are “read” in one particular way within that particular context by that particular audience. Thus, they are partly (almost) visible to one world, often entirely invisible to another. There are differences between seeing a work of art and reading it, between reading a literary work and seeing its visual presence within the space of the page. These are works that are truly hybrid, in which language and image are inextricable and thus must be seen and read—not as two separate acts but multiple ones.

• • •

The selection process began by recognizing that the available categories (of aesthetic approaches, subject matter, nationalities, ethnicities, eras, etc.) flattened a very round, vast, and almost unnavigable world of image+text work. A survey of any kind seemed to me not only impossible but anathema to the nature of the work itself. In the beginning, it became clear that the selection would have to be driven by an act of collection rather than of anthologizing. In other words, I would not be looking for works that could be arranged inside a set of categories of any kind; rather, I would be adding and subtracting as interesting relationships between the works evolved. The process was also fueled by that combination of love and frustration that serves as a kind of divining rod — moving one ever closer to the object of desire that cannot yet be seen. Literally, that meant locating works that were out-of-print, poorly or incompletely reproduced, or entirely unpublished, and figuratively, uncovering works that a different kind of search might reveal.

Early in the process, it became clear that, because of the diversity and breadth of this kind of hybrid work, a series would be necessary. Only then did the criteria for this first collection in the series take shape: (1) that the works make explicit use of image and text; (2) that they play with, subvert, disrupt, or transform narrative in some way; (3) that they can actually be “read” on the page, experienced fully in two-dimensions, in black and white and gray, and reproduce legibly when legibility is intended; (4) that they invite readers to not only engage in unexpected and multiple modes of reading, but also yield something more, something different with each re-reading; and (5) that they are by women. This set of criteria doesn’t have the poetry of a Borgesian taxonomy, but I hope the reader has found the individual works that fulfill it visionary and inimitable — qualities that most often do not obey definition. I also hope that it has provided for a surprising selection with its own, albeit idiosyncratic, coherence. And finally, I hope that the limitations of these criteria suggest what might be possible for future collections in the series.

The sequencing, ungoverned by a chronology, an alphabet, or a list of subjects, reflects a sense of subversion as well as of wonder in its aim to rouse ever multiplying questions. I arranged and juxtaposed the works so that relationships — conversations of sorts — could emerge between the works themselves. The sequencing itself affected the selection: there were many works that fulfilled the criteria, but did they enrich the conversation? There are shared sympathies (in subject matter in some cases, but also in formal strategies, emotional tenor, metaphor, etc.) but the connective tissue is also layered with tensions, expansions, and contradictions. There is, for example, a thread of “domesticity” running from Eleanor Antin’s Domestic Peace through to Hannah Weiner’s Pictures & Early Words, from family and the interior space of home, to the construction of houses, to gardens, weaving, arranging flowers, and shopping, and so forth. But the reader will quickly see that “domesticity” is hardly a theme. Between each of the works in that section of the sequence there are conversations of various sorts about the conceptual application of science, the spaces between the impossible and the unimaginable and the dwellings that can be “built” there, the beauty in banality, the lens of illness, and, among still many other things, the formal manifestations of consciousness — human, animal, omniscient, and polyphonous. If the reader delights in making connections that I may or may not have intended, then the sequence has achieved its ambition: the collection as a cabinet of wonders in which familiar classifications are undermined and new ones emerge, sometimes by arrangement, sometimes by chance.

Beyond the selection and sequencing of the works, the reader’s own experience of the works, individually and in connection to one another, is primary. That is to say, every work is as legible as it intends to be, so that the reader can see the work and actually read it — often not the case with many reproductions. These works ask readers to look and look again, read in one way and then another and perhaps another. Each work —if not reproduced in its entirety as several are — is excerpted substantially, unfolding over several pages and inviting a sustained engagement with the reader so that he or she can discover ways to read it. The collection is not meant to simply represent an artist’s or writer’s work; rather, the work lives on the page and within the form of a book. In some cases, that demanded “translating” the work into two-dimensions, creating a kind of parallel piece that exists with or as an extension of the original installation or sculpture. For example, in the museum, Jane Hammond’s Fallen is an installed platform covered with thousands of leaves; here it is a sequence of single leaves accumulating into an uncountable field: both call close attention to the individual lives lost and to the vast and ever-increasing number of dead. I leave it to exhibition catalogues to document the work with reproductions that offer a more concrete view of a work’s presence in space. Because they are often too distant (literally and figuratively), those images offer one particular way of seeing the work and often no means to actually read it. Finally, where possible, I quote the artist before each work to provide some kind of insight (whether direct or oblique) into the work itself and its particular ambitions, the artist’s practice, how she situates her work as a whole in the world, or even, simply, into the universe of her imagination. I tried to intervene with descriptions only when it seemed the reader might need more contextualization, particularly if the work had been “translated” or excerpted. Otherwise, the works speak for themselves.

• • •

This collection includes twenty-six works by women and excludes the work of the hundreds of artists and writers I considered (and — by virtue of my own ignorance — the work of many, many more). With the designation of “works by women,” it may infer to some a particular gender-oriented agenda. Yet there are books and exhibitions that still exclude women altogether while having no label as a male-only affair or any professed editorial inquiry into gender. If I’d included work by two or three men as well, I might’ve seemed to have turned the tables and eschewed the “women-only” label. But, quite simply, there is still deep gender inequality when it comes to the coveted real estate of exhibitions and publications, and in this collection I preferred to make space — and various kinds of it — for work by women as a very small gesture toward some measure of equality.

Yet, even in selecting work only by women, 300 pages were not nearly enough. I could have easily included twice as many works, bringing some modest attention to a far greater number of women artists and writers whose works deserve much more recognition. But, as mentioned, this book aims to create space for the reader to truly read the work, to be immersed in it. Some works unfold over five or six pages, but others in ten, fifteen, twenty, or more. In order to open the expanse (and thus a wider view of and richer experience with the work itself), I limited the number of works. I excluded several obvious choices simply because those women are already widely and well published, easily located, and (as “obvious choices”) always included in the few other books exclusively reproducing image+text work. There are several very well-known artists I did include because the work itself is lesser-known, because it has not been reproduced in full before or in a way that has made it truly legible, or because the work is rarely, if ever, exhibited. And while I made several more choices with the intention of either historical recuperation or claiming space for younger artists and writers, mostly my selection was shaped —beyond the initial criteria — by looking for the most trenchant relationships between individual works. That they are all by women may very well raise some provocative questions in which gender is a significant factor, but this collection will raise other questions in which it is not. Ultimately, these works were chosen because they incite more questions than answers.

• • •

Of the twenty-six works in this collection, there are only seven that truly live in color. The others are drawings in pencil, oil crayon, black ink or marker, black-and-white photographs, paintings and collages rendered originally in shades of gray, or they are printed matter of black text on white paper. (Of course, the blue lines of Eleanor Antin’s graph paper and the green ribbons of Alison Knowles’ computer printout are lost, but the mind’s eye can easily evoke them as they are utterly familiar.) In making selections for the collection, I did not look only for works that were originally in black and white, but I did rule out many works because I knew they would not translate well to grayscale: they would be illegible and the reader’s experience of them would be utterly deflated. The works in color that I did choose (by Bamabanani Women’s Group, Jane Hammond, Rohini Kapil, Helen Kim, Bernadette Mayer, Charlotte Salomon, and one of Sue William’s paintings) I believe have another life in gray. The nuances of their emotional tones, the content of their subtexts, and the clarity of their formal composition have lent themselves well to reproduction here.

From the beginning, I envisioned the images in this collection in gray. Gray is the color of ambiguity, of it is almost that, of infinite shading, of the in-between like twilight and shadows, of the merging of the white of the page and the black of printed text. Gray is, when reading, unseen but sensed (the figurative gray is always there in the best work). In this collection, gray signals that the familiar modes of reading will not be sufficient—texts do not always appear on pristine white fields; images are not illustrative and language does not explain; stories do not unfold in predictable ways—and yet every page is meant to be read. In gray, there is multiplicity.

—Lisa Pearson

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

May 27, 2024—Eggs, books, etc.: The first book in siglio’s new habitat is just about laid. Our local snapping turtle George perambulated the house in driving rain, determined and curious, then laid her eggs at our doorstep. Do snapping turtles and publishers share common traits? Oh, so very, very slow. Reportedly testy but actually timid. A group of them might be a bale, nest, turn, dole, or creep—though ours seems solitary. Only 10% of her eggs will survive as hatchlings. Make of it what you will. Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers goes on press very soon. One sleeper said to Calle: “I’ve often dreamt of an egg that was enormous ovoid transgression. The original sin of Adam & Eve is a hard-boiled egg.” Meanwhile, many sightings of goslings, kits, poults, and one fawn too: how easily the others propagate, alas.

[...]