Sophie Calle and the Art of Leaving a TraceLili Owen Rowlands, New Yorker

reviews, 11/17/21

The French artist has attained celebrity—and attracted controversy—by pursuing the objects of her obsession. What is she really after?

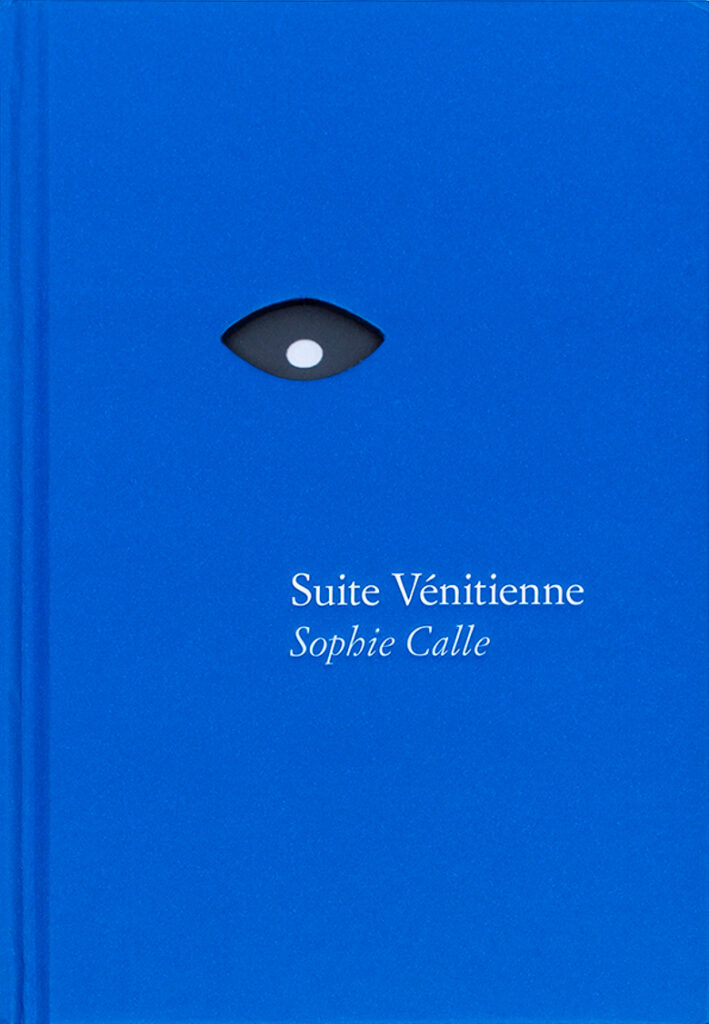

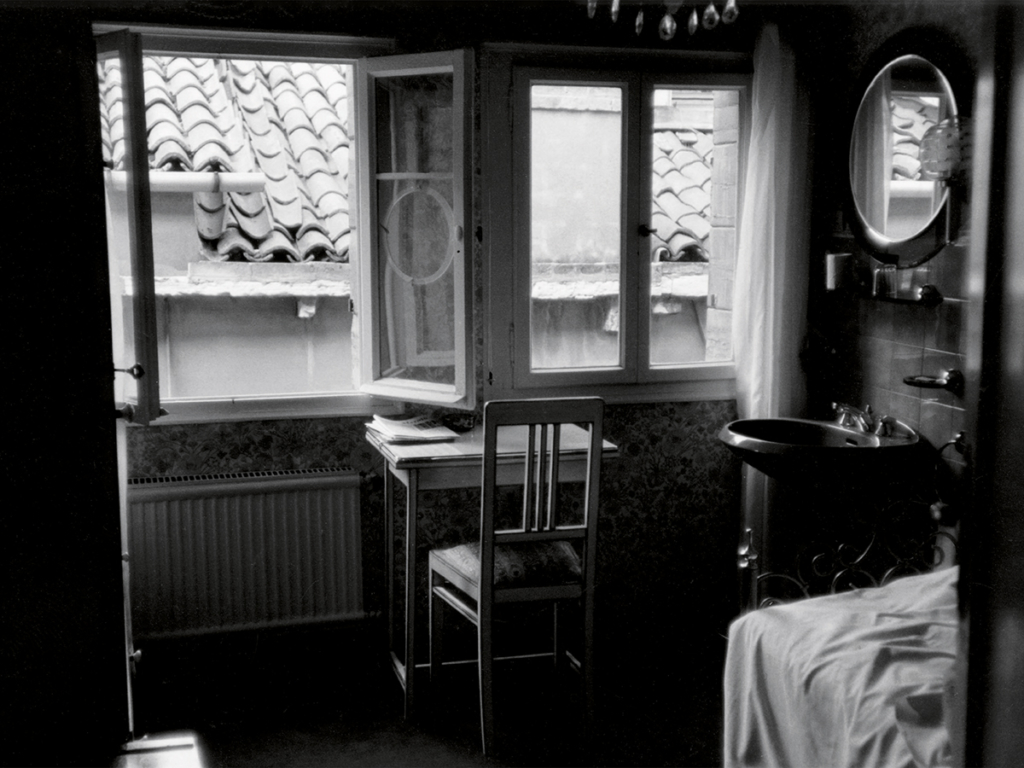

In February, 1981, the French artist Sophie Calle took a job as a hotel maid in Venice. In the course of three weeks, with a camera and tape recorder hidden in her mop bucket, she recorded whatever she found in the rooms that she had been charged with cleaning. She looked through wallets and transcribed unsent postcards, photographed the contents of wastebaskets and inventoried the clothes hanging in closets. Her only rule, it seems, was to leave untouched any luggage that owners had had the foresight to lock. That is, unless they also left the luggage key, which, for Calle, was as good as an invitation.

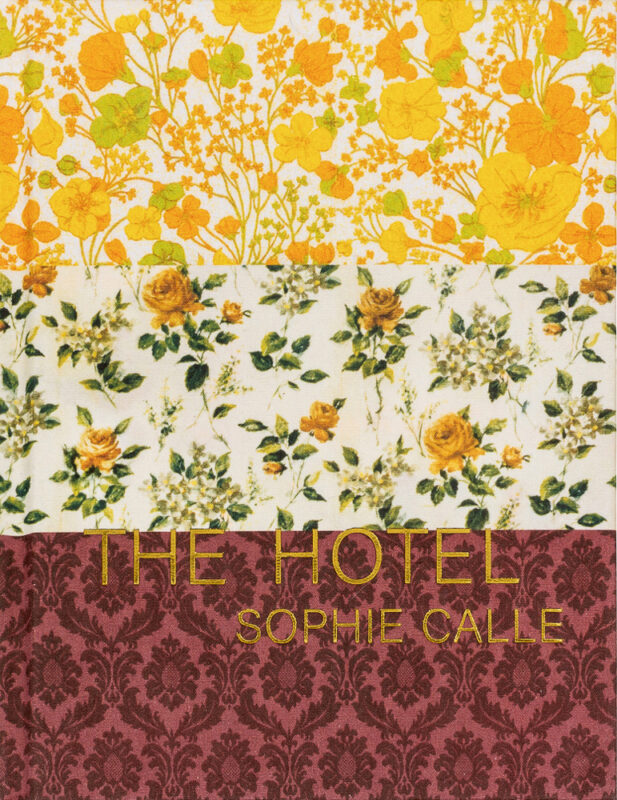

The result of this invitation—or intrusion—is “The Hotel,” a diary, organized by room number, that gathers together photographic documentation and meticulous, often droll observation. (In a set of drawers in Room 30: “socks, stockings, bras . . . very well equipped.”) Calle first presented the project as an installation of large diptychs that paired images with text, and later turned it into a book. Now an English translation has been reissued by Siglio, in a clothbound edition with pages edged in gold.

It is an especially sturdy and opulent artifact for a project chiefly concerned with what is transient and ordinary—the ephemera of strangers. In an embroidered handbag apparently belonging to a Frenchwoman, Calle finds five hundred and forty-five francs and a sixteen-year-old telegram sent from Chicago that reads “What is going on darling?” In Room 12, where two Viennese men are staying, she discovers a brass candlestick, dinner jackets, and a copy of Freud’s “Totem and Taboo.” A pair of Italian women, a truck driver and a sales clerk, have brought with them three porn magazines, two sets of flannel pajamas, and one Teddy bear. Calle photographs the chintzy hotel décor—Baroque wallpaper, dark bed frames, gilt sconces—in vibrant color, and smaller details in black-and-white: a pair of pressed Y-fronts in an open drawer, a handkerchief soaking in a glass of water, a steady accumulation of medicines on a nightstand, the crease on a bedsheet where someone has recently lain.

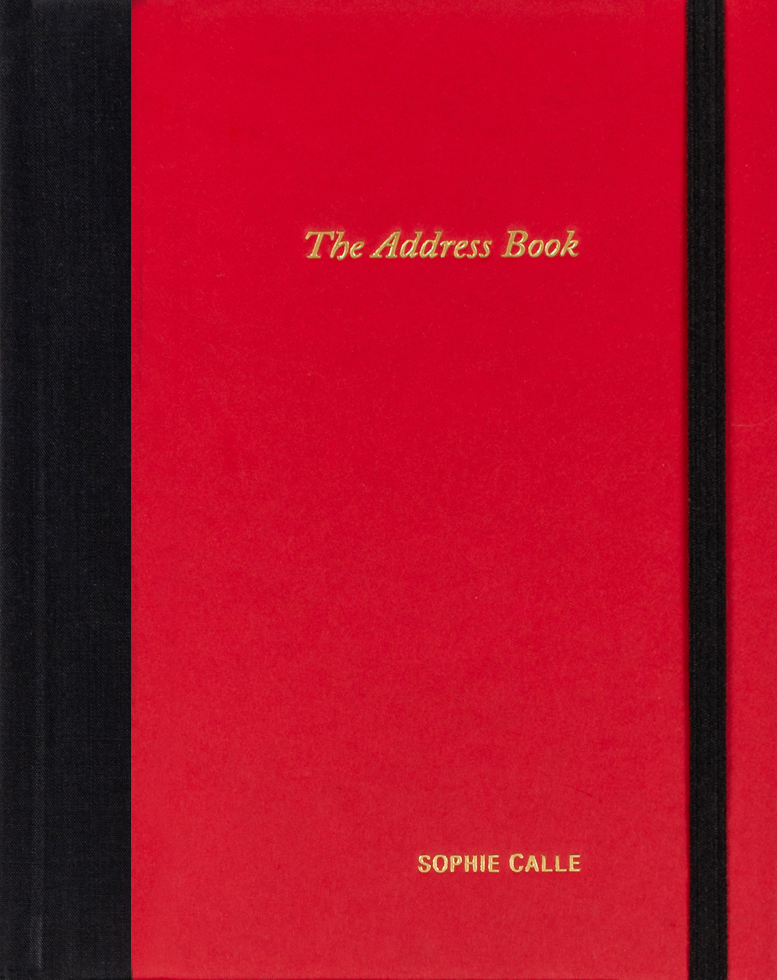

In the four decades since “The Hotel” first appeared, the imprint has remained Calle’s preferred form; she uses the negative space where someone has been to discern their outline, like a painter whose sitters have got up and left. The absence of her subjects, as in the vacant rooms of hotel guests, is often literal. A 1983 project began when Calle found a stranger’s address book in the street. She returned it to its owner, a documentary filmmaker, but not before photocopying its pages. In “The Address Book,” she interviewed the man’s contacts to form a composite portrait of him in absentia: “thirtyish, white hair”; “a little obsequious”; “a flat Woody Allen, with no pizzazz.”

Sometimes the absent subject is Calle herself. In “Take Care of Yourself,” perhaps her best-known piece and France’s entry for the 2007 Venice Biennale, Calle invited a hundred and seven women to interpret a breakup e-mail that she’d received from a former boyfriend in whatever way their profession dictated. A corporate headhunter compiled a report on the ex’s (limited) employability; a clothing designer reimagined the message as a patterned crisp blue shirt with an organza collar. Calle’s own response, if she has one, is not included, but through the words of the other women the shape of the relationship shades into view.

Although there is something oblique about these conceits, Calle is associated, above all, with acts of bald exposure. Her celebrity, which now extends far beyond France, has long been attached to charges of voyeurisme and exhibitionnisme (which have sometimes resulted in legal trouble). Yet, as “The Hotel” vividly shows, what Calle is really looking for is more enigmatic and compelling than other people’s dirty laundry. Rather than erase the residue of human presence, as a “real” maid is expected to, Calle does the opposite, preserving every stain and scrap as a sign or symbol. But of what? This is the question at the heart of Calle’s work, and the answer may hardly be the point; what interests her most is the seduction and projection involved in knowing another person—how fantasy intervenes in every attempt to see and be seen.

Continue reading at the New Yorker

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

october 23, 2024—a sojourn across the sea for the Small Publishers Fair in London! Our intrepid publisher has lugged three suitcases with the most minimum of clothing to maximize the books—almost 150 pounds of them. (For the lucky few, a first glimpse of Sophie Calle’s The Sleepers!)

[...]