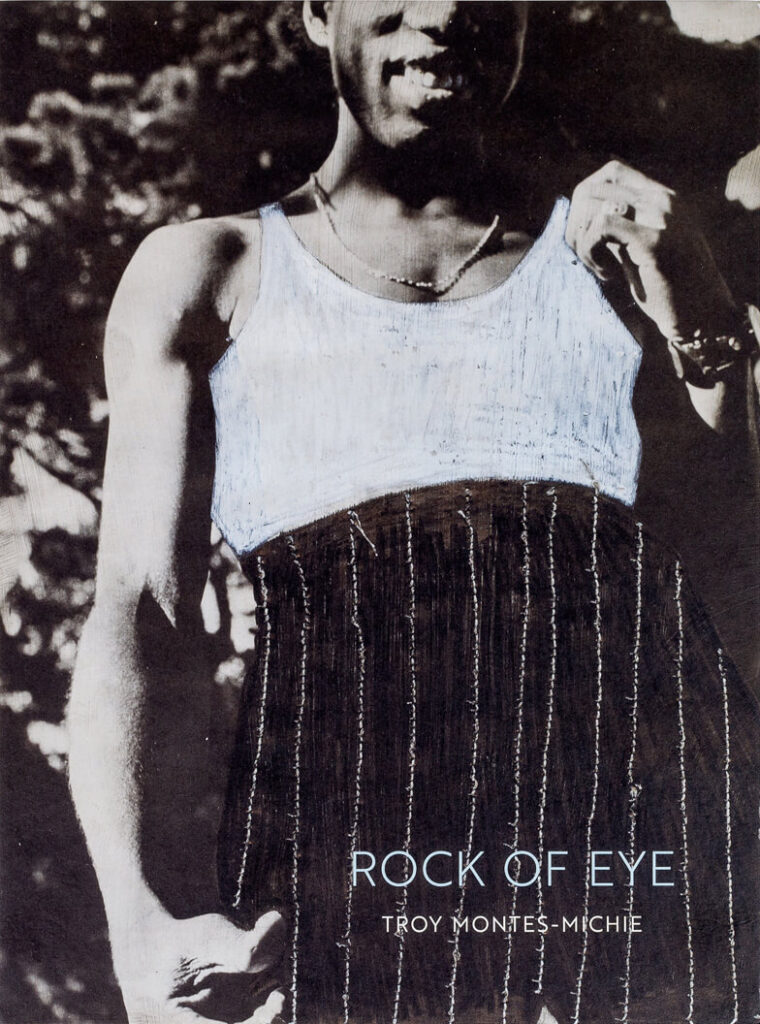

The BeholderIn Rock of Eye, Troy Montes-Michie refashions the dominant gaze upon Black masculinityRasheeda Saka, Alta

reviews, 12/20/21

Suture and sew share a root in the Latin suere, which means “to join” or “to fasten together.” Although both words express a certain primacy of precision, they are generally employed in different contexts—the first having to do with medicine or surgery and the second with the making of garments and the accentuation or obfuscation of one’s physique. In Rock of Eye, however, the artist Troy Montes-Michie seeks to reconnect them, exploring what it means to fashion oneself out of stultifying objecthood, emphasizing the materiality of experience, feeling, and instinct in his collage, portraiture, and painting.

“I am interested in the idea of redirecting the circulation of these images [of Black men] by reanimating the past and confronting the present,” Montes-Michie explains. This aesthetic impulse animates his preoccupation with the bodies of Black queer men, which opens up the possibilities of different intimacies, terrains, and visual experiments while remaining acutely attuned to fraught histories and violence.

Rock of Eye accompanies Montes-Michie’s upcoming solo exhibition at Los Angeles’s California African American Museum. (It will run from February 16 to September 4, 2022.) The book is a stunning and ambitious assemblage of repurposed and revised images, among them reproductions of ephemera and historical artifacts, taken from sources including vintage erotic magazines and collections of French tailoring. The result is a series of collages, sensuous portraits, layered embroidery, and skillful stitching patterns that distort and reframe the ossifying gaze we turn on Black men. “Each gaze is poised as an invitation but my critique is in the consumption of idealized body types, fetishization, and the performative aspects of masculinity,” Montes-Michie notes. The very act of looking becomes troubled, meant to make us confront our expectations and how we are implicated in that gaze.

Some of the images here, for example, present nude Black men covered by vertical white stitching patterns, which may be interpreted as the bars of a cage or the suturing of a wound. The men face away from the camera, their backs to us, anonymous but not unknown. In many images, Black men look directly at us, as if in curiosity or invitation. Still more show Black men with their genitals covered through painting or stitching or drawing; some touch themselves, but we are able to “see” this only in how they position their bodies—through implication, in other words. “By choosing to hide or remove the phallus,” Montes-Michie writes, “I am hoping for an alteration to the stereotypes placed on the Black male solely being reduced to their endowment and to notions of hypersexualization.”

For all that, the erotic potential of these images is never quite diminished; it lingers and is refracted, moving our eyes in different ways. Juxtaposing photographs of queer Black men with other images, Montes-Michie’s collages commingle disparate contexts. That creates a nexus of affect, blurring the line between refusal and cohesion, disunity and liberation. To encounter this work is to experience feelings of wonderment, enthrallment, ambiguity, and anarchy.

Continue reading at Alta

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

May 11, 2023 — It was spring. And then it was not. And now it is again. How far can you throw a ball? What if one could travel along a high arc, across a continent, an ocean? What if you could travel with the ball, see as it might what is above and below? And I wonder what its speed might be? Enough to stay aloft, but slow, not even so fast as a swallow? That was once how a single season felt. Now…

[...]