“Stitching is a violent and healing act”Megan Liberty, Brooklyn Rail

reviews, 02/15/22

Originally published in the February 2022 issue.

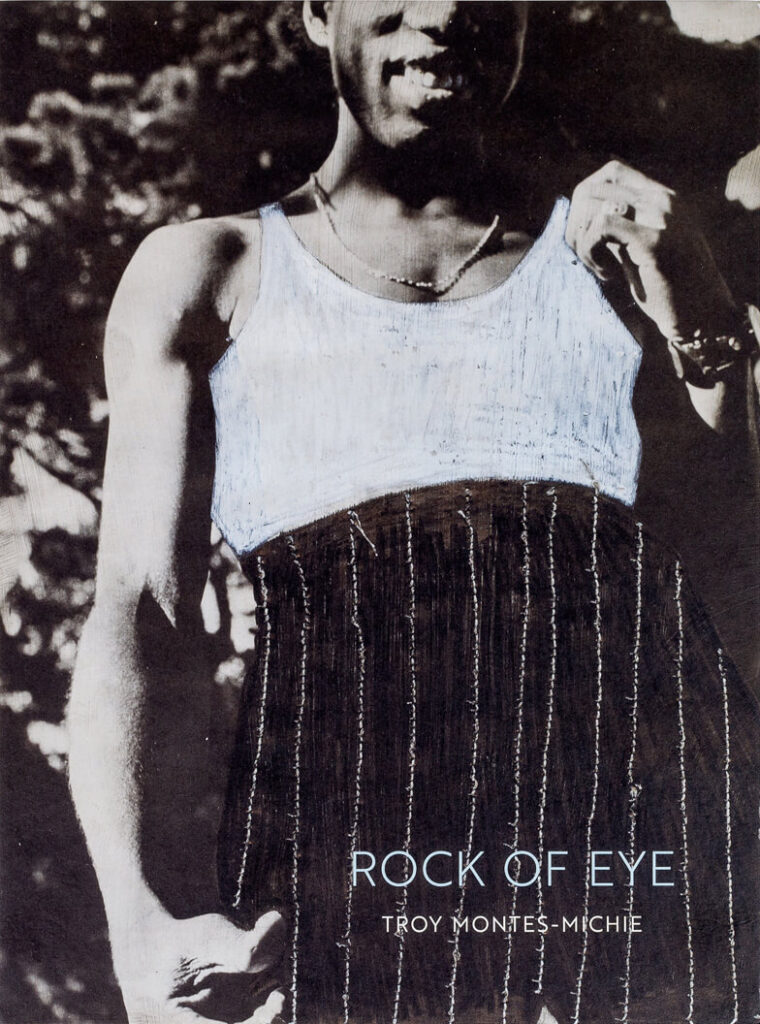

Troy Montes-Michie’s artwork is marked by the stitch. The stitch has a long, gendered social history, rooted in craft, domestic work, and women’s embroidery. Stitching is also a violent and healing act—puncturing as well as uniting—and can be used both functionally and decoratively to inscribe a tactile pattern onto something. Montes-Michie makes use of these multiple interpretations and histories of the stitch and men’s fashion and tailoring in his multimedia collages to explore masculinity, sexuality, and marginal identities (both metaphorical and geographical). Rock of Eye, a new book published on the occasion of his traveling solo show, gathers his collages of gay pornography, sewing pattern pages, men’s fashion and tailoring magazines, and quilted patterns, bound between raw-edged case boards with an exposed book block that leaves the yellow stitching of the book visible from the spine and the margins of the pages.

Montes-Michie grew up in El Paso, Texas in the borderlands between the US and Mexico in what he refers to as a “third space” that was his “first experience with the language of collage. The whole environment is an amalgam: two separate cultures colliding on every level,” he tells Brent Hayes Edwards in the interview included in the book. Blended, collaged identity is central to his artistic practice, as is his understanding of outsiderness, otherness, and the reductive ways Black and brown bodies are perceived, especially when it comes to borders. Rather than approach this directly, Montes-Michie investigates these multilayered notions of identity and visibility through the stich, employing the visual language of fabric and fashion to make larger statements about Black male (in)visibility. As the book title—a reference to a method of tailoring done by eyeing how fabric falls rather than measuring it out—suggests, Montes-Michie’s figurative collages give weight to the lived experience of men on the border rather than the long-held cultural presumptions.

The book opens with endpapers showing pattern pages, enlarged so the slight ripples and crease in pages are visible, emphasizing their fragility and materiality. Pattern pages reoccur throughout, incorporated into portraits and reproduced as full pages, like a pause between the figures. But the starting point for most of the works is gay pornography featuring Black men. “I came to realize what drew me to these materials was the way men of color were placed in a suspended state of objectification,” Montes-Michie explains. “It upset me. Since most of the photographers were white, the real question was about the gaze: what it meant for certain bodies to be viewed or desired by white men.” Collaging magazine pages together and adding in hand drawn items of clothing with ink, grease pencil, and thread lines, Montes-Michie conceals the men’s bodies, so much so that it’s not until a dozen pages in that we realize the erotic nature of the source material.

The first few images almost seamlessly (though of course the images have many visible seams) present scenes of men standing in fields of grass or near plants in fashionable wide-legged pinstriped zoot suit pants. Montes-Michie not only uses the visual imagery of sewing and men’s fashion, but also taps into its rich cultural history. The zoot suit in particular is itself a kind of wearable collage—popularized in the 1940s and associated with Black jazz musicians and the Pachuco counterculture—it represents a blended and self-made identity. It was seen as a powerful means of “self-fashioning,” in Montes-Michie’s words. Curator Andrea Andersson contributes an essay that further elucidates the history of this men’s fashion item and the Zoot Suit Riots they sparked in the 1940s, adding a deeper context to the collages and illustrating the research behind Montes-Michie’s images.

These references to the racial history of fashion hint at larger questions: who is afforded privacy and who has the luxury to be unobserved? In Montes-Michie’s scenes, Black men are given these luxuries that historically have been withheld: privacy and agency. An image of a man reclining on a bed masturbating performatively is transformed into one of a man pensively resting, daringly meeting the gaze of the viewer. In a moment when conversations around the policing of Black bodies in public space continue to grow and gain momentum, Montes-Michie’s quiet scenes of interiority, of “reclamation”—to use Tina Campt’s word from her essay in the book—dramatically change the context.

Continue reading at the Brooklyn Rail

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

April 11, 2024 — The spring peepers have thawed (these little frogs freeze in winter) and now, unabashedly randy, they chirp. At first there was one, then two, and now it sounds like thousands. Two days ago, when it was truly spring, their adamantine chorus was almost deafening (we closed the windows to simply think!). Siglio has relocated to a lush, thriving hollow at the furthest most edge of the Berkshires after two years of peripatetics, sans library—which is now unpacked in a less than Benjaminian manner (little time to contemplate—our urgency in getting books on shelves mirrored the peepers need to mate). The first few months of 2024 were almost unendurable, but we’re home, spring is here, and there are books to made. We are singing!

[...]