Editor’s ChoiceBruce LaBruce, BOMB Magazine

reviews, 03/02/22

Originally published in issue #159, Spring 2022

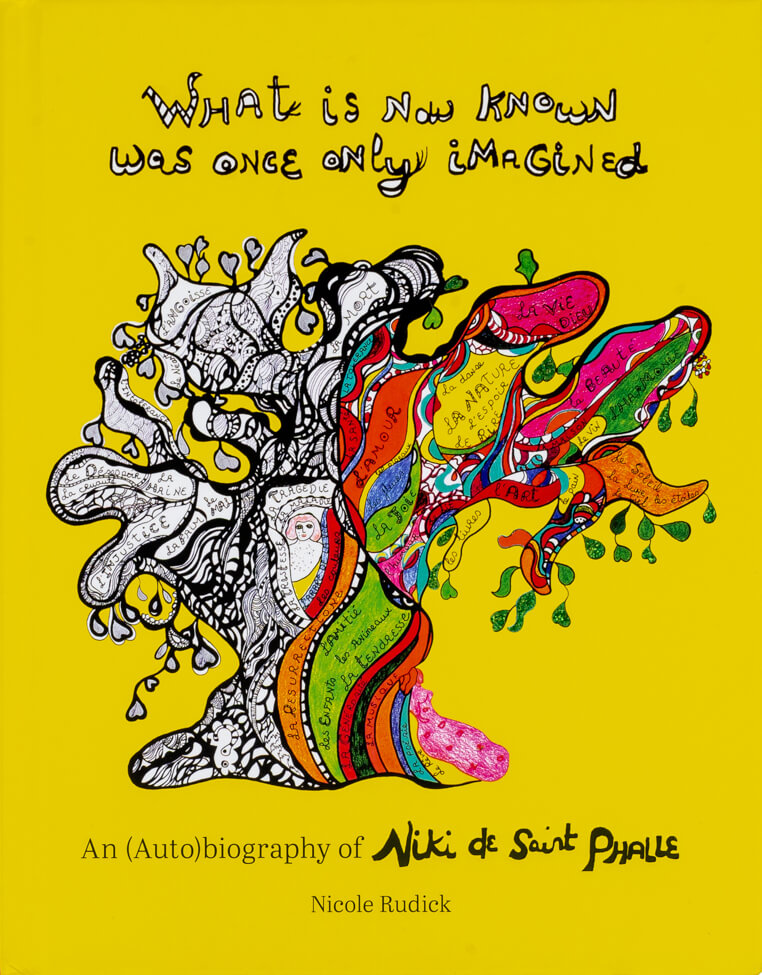

Its title alluding to a William Blake quote, What Is Now Known Was Once Only Imagined is a sublime and stimulating “(auto)biography” of the late French-American artist Niki de Saint Phalle (1930–2002). Edited by Nicole Rudick, the visually splendid book brings to life all the complexities and contradictions of the legendary sculptor, painter, and filmmaker. By strictly relying on Saint Phalle’s own writings, scribblings, letters, memoirs, essays, and often text-heavy graphic artworks, Rudick adroitly creates a loose narrative of the artist’s unruly life while resisting interpretation. The result is a kind of legerdemain of editing without judgment or speculation, an open text that invites the reader to linger on Saint Phalle’s lushly reproduced imagery and to contemplate her inextricably linked work and life. (I suggest using a magnifying glass, as I did, to explore the artist’s intricate drawings and occasionally tiny handwriting.)

The narrative that Rudick presents is frank and unsparing, starting with the child Niki, who wanted to be half woman, half man, eschewing any fixed identity, and was aware very early on that she was born into a man’s world. Recognizing the power and freedom her father exhibited, and witnessing the entrapment felt by her mother, Saint Phalle developed a protofeminist sensibility, but not one that would ever be expressed by identification with orthodox feminism. We discover that in her private girls’ school, Saint Phalle was chastised and threatened by the headmaster for writing “wild pornographic pages” about her attractive male cousin. Throughout her life, Saint Phalle had turbulent romantic and sexual relationships with difficult men. She eloped at eighteen and became a mother at a young age, and later left her husband and two small children to pursue her art full-time. It was a choice both liberating and torturous: “I felt that I had done such a terrible thing… that I buried myself 100% in my work for the rest of my life to make up for it. I needed to prove that what I had done had not been in vain and had been worthwhile.” It should be noted that Saint Phalle did not abandon her children and remained a strong presence in their lives.

The book contains numerous handwritten, illustrated, and typed letters to friends and supporters, in which she reflects on different stages of her social and family life, and her career. The letters also recount, in detail, the realization of several major projects, such as the Nana Maison sculptures,

HON, and her enormously ambitious Tarot Garden, a fourteen-acre sculpture garden built in Tuscany. Her partner of thirty years, the Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, is mentioned throughout the book as a source of inspiration and as a constant collaborator in the challenging production of her colossal sculptures. A letter addressed to him after he died pays homage to their unique artistic bond.

When Saint Phalle was in her twenties, her father admitted in a letter to having raped her when she was eleven years old. Her summary of the event is painfully matter-of-fact: “The Summer of Snakes was when my father, this banker, this aristocrat, put his cock in my mouth.” It was the same summer that she happened upon two black copperhead snakes locked in a death grip. And it was the same summer that her brother put a dead snake in her bed because he was jealous of her being taller than him. It’s not at all surprising that snakes appear frequently in Saint Phalle’s work and that her experimental film Daddy (1972) ends with a symbolic killing of her father, by shooting a sculptural depiction of his body. (She was already infamous for her Tirs or Shooting Paintings, in which she fired guns to explode paint-filled bags embedded in her sculptures.) In the voice-over in Daddy, she says, “Mother, I have marvelous news: finally, Papa is dead.” The film, which evokes Sylvia Plath’s brilliant poem “Daddy,” created a scandal; according to the artist, “Only my mother, some rare critics, and Jacques Lacan stood up for me!”

Niki de Saint Phalle led a life of genuine passion and obsession. She not only lived her art, but at times actually lived in it. She experienced torment but also great joy and freedom, and evinced a strong compassion for others. “I have been a wild, wild weed. Done everything. It’s possible in art to be a rebel and to experiment. Now I am much more concerned with bringing joy.”

Continue reading at BOMB Magazine

see also

✼ consideration:

“Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera … achieves the hidden aim of all postmodern work. Namely, befuddling the reader with the dilemma: is this sheer brilliance? Or merely incomprehensible nonsense?”

[...]