An Abbreviated Charlotte Salomon Biography

affinities, 03/26/12

Selected and arranged by Niyati Shenoy

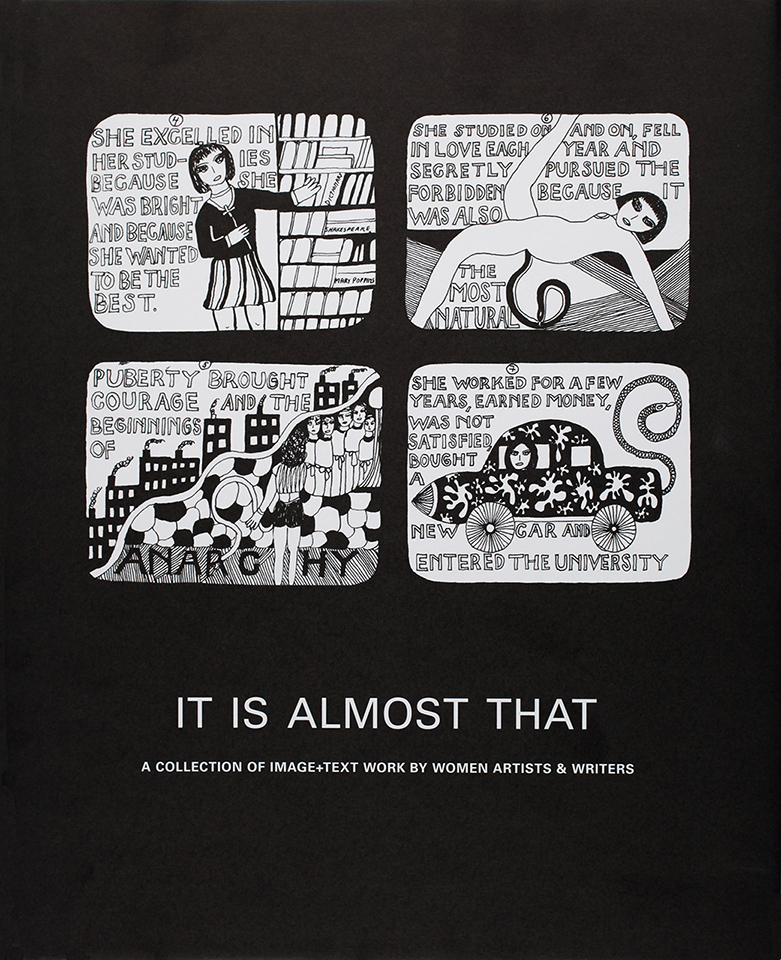

An excerpt from Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theater? A Song Play is a cornerstone of Siglio’s 2011 publication It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers. One of my aims in editing and publishing the book was to bring attention to artists and writers who have been overlooked or too tightly categorized and thus are known to a only a very particular audience. Salomon is certainly case in point. While the inclusion of her work in It Is Almost That may help to remedy that, this blog post—authored and organized by Siglio intern Niyati Shenoy—pulls together disparate sources of information to serve as a kind of hub and as resource for readers looking for ways to navigate (sometimes sparse) material on artists and writers who are not (or not yet) as well-known as we think they should be. See our other post on Unica Zürn and my short biography of Dorothy Iannone published in You Who Read Me With Passion Now Must Forever Be My Friends, 2014. —Lisa Pearson

1.

“I will live for them all.”

On the 10th of October 1943, Charlotte Salomon, a German Jew from Berlin, was executed upon arrival at Auschwitz after being deported from her exile in France. Before her death, Salomon had completed an epic visual autobiography entitled Life? Or Theater? (Leben? Oder Theater? Ein Singespiel) comprised of more than 1300 pages of drawings with text. The work was dedicated and later entrusted to Otillie Moore, an American woman who owned the garden cottage where Salomon lived in France and who returned it to Salomon’s father and stepmother who survived the war. The work is now in the care of the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam.

Structured in three parts—a prelude, the main section, and an epilogue—Life? or Theater? traverses three generations of Salomon’s family’s history during the decline of Weimar Germany and the Nazis’ rise to power. It employs sophisticated narrative techniques (both visual and textual) to create shifts in perspective and time as the stories unfold, double-back, and are re-envisioned from varying points of view. The text is, in the beginning, often written on overlaying tracing paper in ways that mirror the painting beneath. Later, much more of the text is actually painted on the page or, if written on the overlays, Salomon’s scrawled cursive suggests both the emotional urgency of the work as well as the pressure of bringing it to completion. Her visual composition also evolves through the course of the work, using methods of the Modernists, the Old Masters, as well as Medieval illuminated manuscripts.

Source: Introduction to Charlotte Salomon, “Excerpt: Main Section, Chapter 7: A Young Girl,” from Life? Or Theater? A Song Play in It Is Almost That: A Collection of Image+Text Work by Women Artists & Writers, edited by Lisa Pearson, Siglio, 2011.

2.

“This play is set in the period from 1913 to 1940 in Germany, later in Nice.”

Salomon was born to a well-to-do assimilated Jewish family in the wealthy Charlottenburg district of Berlin on 16 April 1917. Her happy, early life consisted of grammar school, governesses, and holidays to the Alps. Then at the age of nine, Salomon lost her mother. While she was told it was influenza that had killed her, her mother had, in fact, committed suicide.

In September 1930 her father Albert Salomon, a surgeon, married his second wife, Paula Lindberg, a highly regarded singer. When the National Socialist Party came to power in 1933, Salomon’s life changed dramatically again as her family endured restrictions on their professional lives. Dr. Salomon could now practice medicine only at the Jewish Hospital, having lost his right to practice surgery as well as his professorship. Lindberg was permitted only to sing at the theaters and synagogues of the Kulturbund deutscher Juden, an organization that became the center of Jewish cultural life. Lindberg’s circle of friends in this period included artists and scholars such as Paul Hindemith, Kurt Singer, Erich Mendelsohn, Albert Einstein, and Rabbi Leo Baeck, and Salomon was often silent witness to their discussions. Salomon left school due to increasing anti-Semitic hostility and was increasingly confined to her home as she began to take private drawing lessons in preparation for entrance to art college. She was admitted to the State Art Academy in 1936 under a rule that stipulated 1.5 per cent of students could be Jews provided their fathers had served at the front during World War I (Albert Salomon had been an army doctor).

One of the first people to take Salomon’s art seriously was the music theorist Albert Wolfsohn. Paula Lindberg hired him as her music teacher as he needed a job to be protected from arbitrary deportation. He soon became a fixture in the Salomon home, not only working with Lindberg, but also engaging and critiquing Salomon’s work. He was also the object of Salomon’s intense fascination and infatuation.

In 1938, during a period of particularly intense anti-Semitic persecution following Kristallnacht, Albert Salomon was arrested and temporarily interned in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Once Paula was able to procure his release, she and her husband decided to send their daughter to Villefranche in southern France to live with her grandparents who had left Germany in 1934 and rented a house from a sympathetic American landlady, Otillie Moore. Soon after Germany invaded Poland and the war began in 1939, Salomon’s grandmother committed suicide. Once Germany and Italy declared war on France in May and June 1940 respectively, French authorities of the Vichy regime began interning immigrants and Jews in particular. Salomon and her grandfather were sent to a camp in the Pyrenees but allowed to return to Nice after only a month. When she was released, after the crisis of her grandmother’s suicide as well as learning that her mother had ended her own life as well, Salomon began working obsessively on Life? Or Theater?, rarely eating or sleeping, until it was complete by the end of the summer of 1942. Her grandfather passed away of natural causes about six months later.

By then the Mediterranean coast of France had been occupied by Italy, and in September 1943, by Germany. Life since 1942 was increasingly perilous and difficult for Jewish refugees who were forced to conceal their identities; but Salomon had help; as she wrote when her American landlady departed, ‘Mrs Moore left me a friend. I didn’t know quite what to do with him.’ When Salomon fell in love with and married this man, Alexander Nagler, an Austrian businessman, in June 1943, they made the mistake of registering their marriage, which alerted the Germans to their presence. On the evening of September 24 that year, a Gestapo truck drew up outside their house in Villefranche and took them away to their deaths. Salomon was twenty-six years old and four months pregnant.

Abridged from Life: Biography 1917–1943, by Christine Fischer-Defoy and Judith C.E. Belinfante, p. 15–26, from Life? Or Theater?, Charlotte Salomon, Waanders Publishers, Zolle, 1998.

3.

“I will create a story so as not to lose my mind.”

At a transport camp on the way to Auschwitz, Salomon listed her occupation as ‘graphic artist’. During her detainment at the previous camp in the Pyrenees in 1940, following the terrible revelation of suicides in her family, she had observed many artists produce work amid wretched conditions. Upon her release from that camp she had written to her parents, ‘I will create a story so as not to lose my mind’.

In Life? Or Theater?, writing herself in the third person from the departure point of this moment of choice between ‘whether to take her own life or to undertake something eccentric and mad’, Salomon narrates, ‘with dream-awakened eyes, she saw all the beauty around her, saw the ocean, felt the sun, and knew: she must disappear for a time from the human surface, and sacrifice everything for this – to recreate herself from the depths of her world. And from that emerged Life? Or Theater?.’ When the work was finished she gave it to a friend of her husband-to-be, Doctor Moridis, saying, ‘Keep this safe. It is my whole life.’ He passed it on to Otillie Moore after the war was over.

Salomon had depicted in her work all those who were closest to her. She writes in her introduction to it, “The varied nature of the paintings should be attributed less to the author, than to the varied nature of the characters to be portrayed. The author has tried…to go completely out of herself and to allow the characters to sing or speak in their own voices. In order to achieve this, many artistic values had to be renounced, but I hope that, in view of the soul-penetrating nature of the work, this will be forgiven.”

Source: Charlotte Salomon: 1917–1943, by Mary Lowenthal Felstiner, Jewish Women’s Archive online.

4.

“Do you really love me?”

In 1961 the first exhibition of Life? Or Theater? was undertaken by Amsterdam’s Stedelijk museum. Paula Lindberg sent a brochure of the exhibition to another character who had appeared prominently in the work – Albert Wolfsohn. Wolfsohn had emigrated to England in 1939 and enlisted in the army. He was completely devastated to see pictures of himself with her [Salomon] and to realize how much he had in fact misunderstood the impression he had made on her. He was deep in thought for two days.

Albert Wolfsohn is given the pseudonym Amadeus Daberlohn in Life? Or Theater? – a reference both to Mozart and to Wolfsohn’s impoverished state. Of the 769 paintings that ended up in the final version of Salomon’s work, almost four hundred of them relate to or contain him, and are entitled ‘The Main Section’. He leaves Salomon with the benediction, ‘May you never forget that I believe in you.’

Wolfsohn was born in 1896 in Berlin, and studied literature, art and music. He played the piano, violin and viola. In 1914, before he could enroll to study law he was conscripted into the army, and fought on both the French and Russian fronts. A painful experience in battle where he was unable to save the life of an injured comrade crying out for help left Wolfsohn scarred for life with guilt and emotional trauma. Eventually he was able to find solace in the study of art and music, and became preoccupied with helping other people to express themselves artistically and find fulfillment – he has been quoted saying that all his work was the expression of a deeply entrenched saviour complex, ‘bound up with the need to help people, almost to an idiotic degree.’

By the time Wolfsohn returned to Berlin in 1930, his interests had coalesced around the human voice and its capacity to express the soul – a concept that had intrigued him even as a child. To support his sick mother, Wolfsohn played the piano for silent films, tutored schoolchildren at math and worked in a bank; on the side, he was a voice teacher. He had begun to write a work, entitled Orpheus, Or the Way to a Death Mask, which Salomon liberally excerpts and quotes verbatim in Life? Or Theater?. Orpheus derived its title from the mythical Greek figure, who must descend into the despair of the Underworld, into the depths of his own psyche, in order to find his lost wife, his anima or soul, his voice.

Salomon was a puzzle to Wolfsohn—he wrote to a friend of hers after the war that he had found her ‘extraordinarily taciturn, quite unable to break through and emerge from the barrier she had built around herself. I felt compelled to attack this barrier but when I talked to her, trying to break it down, she would gaze at me with such a challenging look which spurred me on to even greater activity, forcing me to play the clown…I always felt I had to bring her closer to reality, there was such an air of unreality about her.’

“Whatever induces me to play this ridiculous role?” he asks. “What forces me to go on talking in a never-ending torrent of words? What makes me speak about every deep realization? Only because I want to help a little? – a bit embarrassing, isn’t it?”

Source: Albert Wolfsohn alias Amadeus Daberlohn: The Man and his Ideas, by Sheila Braggins, a lecture at the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam, September 2007, accessed online.

5.

“A tune suddenly enters her mind.”

Various scenes and chapters of Life? or Theater? are “accompanied” by music or have notations as to which dialogue should be sung. It was intended as a Gesamtwerk. Salomon’s work makes references to several kinds of music – Carmen by Bizet, Orpheus & Eurydice by Gluck, lots of Bach, Schubert, folk songs and popular film tunes – and contains many musical themes that are often used and repeated in different sections to melt together scenes of joy and tragedy, irony and comedy. Salomon was introduced to much of this œuvre by her stepmother, Paula Lindberg-Salomon, and uses them to set a mood that becomes integral to her work.

She narrates, ‘The creation of the following paintings is to be imagined as follows: A person is sitting by the sea. She is painting. A tune suddenly enters her mind. As she starts to hum it, she notices that the tune exactly matches what she is trying to commit to paper. A text forms in her head, and she starts to sing the tune, with her own words, over and over again in a loud voice until the painting seems complete. Frequently, several texts take shape, and the result is a duet, or it even happens that each character has to sing a different text, resulting in a chorus.’

Life? Or Theater? is best appreciated in conjunction with its musical score. The Jewish Historical Museum’s archive has clips of music appended to the paintings in which they are mentioned.

Quotes by Charlotte Salomon at the beginning of each section:

- From Charlotte Salomon: 1917-1943, by Mary Lowenthal Felstiner, Jewish Women’s Archive online.

- From Life? Or Theater?, Charlotte Salomon, Waanders Publishers, Zolle, 1998: pg 43.

- From Charlotte Salomon: 1917-1943, by Mary Lowenthal Felstiner, Jewish Women’s Archive online.

- From Life? Or Theater?, Charlotte Salomon, Waanders Publishers, Zolle, 1998: pg 508.

- From Life? Or Theater?, Charlotte Salomon, Waanders Publishers, Zolle, 1998: pg 45.

see also

✼ affinities:

“I can not understand how you … would publish such filth. The book cost $39.95. This was not works of art.”

[...]