How a symbol of god comes alive next to a smudge or smearIntroduction to Tantra Song: Tantric Painting from RajasthanLawrence Rinder

excerpts, 09/24/11

Introduction to Tantra Song: Tantric Painting from Rajasthan, edited by Franck André Jamme. All rights reserved. © 2011 Lawrence Rinder and Siglio Press.

I have a place in the country. I doubt there’s anything truly special about it: it’s just a little piece of California countryside, nothing more. Yet, at that place, when I can look at a tree, a constellation of stars, or even just a small patch of ground, it looks wonderful and strange. I have little idea what I am looking at, even though I might be able to give it a name, or perhaps recall some principle of nature that has made it as it is. What I see is color, texture, shape. I see energy, evidence of change, and the transforming powers of life and death.

Franck André Jamme’s collection of Tantric images affects me in a similar way. Just little scraps of paper really with barely a mark upon them. Simple. Anonymous. Repetitive. But utterly riveting. I can’t begin to say what these images are. I know virtually nothing about the tradition from which they spring. I sense that they are in some way technical and have a use in that tradition which is tool-like and, in some spiritual way, pragmatic. My fascination with them is likely as confused as that of the Hindu adepts who not long ago chose to enshrine a parking barrier in San Francisco, finding in it an echo of the divine. In these divine images, I find an echo of art.

It helps that I have a very broad definition of art, one that could even include those engrossing patches of bark, soil, and sky. Maybe art isn’t quite the right word: let’s call them experiences that ground us in the real, images that cut to the quick of what we might be. Obviously, things like this need not have an origin in human intent and certainly don’t require skill as commonly understood nor, for that matter, professional acumen. They have to have something but it is impossible to describe what that is. We can call it beauty.

I have noticed in the Tantric works how the simplicity of their conventional, geometric forms is complemented by the infinite complexity of their particular execution: water stains, flaws in the handmade paper, fragments of unrelated text combine to make each work not only unique but somehow perfect. These images would clearly not have the same power if they were drawn on a computer and digitally printed. It’s not just a desire for the antique or a nostalgic patina that makes the incidental marks so important, it’s precisely that ideal forms—forms plumbed from the depths of the mind, of the soul—need to co-exist with randomness and the emptiness of chance. How is it that a symbol of god alone is so dull, but when juxtaposed with a smudge or a smear it comes alive? Ever since I moved to the country I’ve fantasized about sleeping at night in the woods, with a blanket maybe but nothing else to separate me from the world and the life around me. I haven’t done it, but I see in these Tantric images what such exposure might feel like and what awareness it might lead to.

I first saw Franck’s collection of Tantric art in the mid-1990s at a sidewalk café in Paris. I was on my way to India and I had contacted Franck to get his recommendations on artists to see. He brought along a portfolio of small paintings which, when opened, had the alarming effect of making Paris vanish. Of course, I asked Franck how I could find some in India and find the people who make them. He gave me some tips, directing me to Rajasthan and providing me with a couple of names. The search led me to Jaipur, Jodhpur, and Jaiselmer, to old markets and dusty back rooms. I found some marvelous Jain pieces, but nothing approaching the lucidity of the works in Franck’s collection.

The closest I came to touching something like a point of origin was at a rendezvous with the director of the Museum of Indology in Jaipur. The old fellow, Acharya Vyakul, was himself a tantrika and exceptionally cagey about the type of thing I was looking for, although he had some related works on view in his jumbled display cases. It wasn’t until well past midnight that he revealed that he had some pictures I might like to see, paintings he had done himself. They were not as precise as Franck’s and departed at times from conventional forms. Yet they had some spirit in them and I acquired three for my museum. Ultimately, I’m afraid that I fall into the category of foreigners who Franck has known who, “went too quickly over there—apparently because they didn’t have the time.”

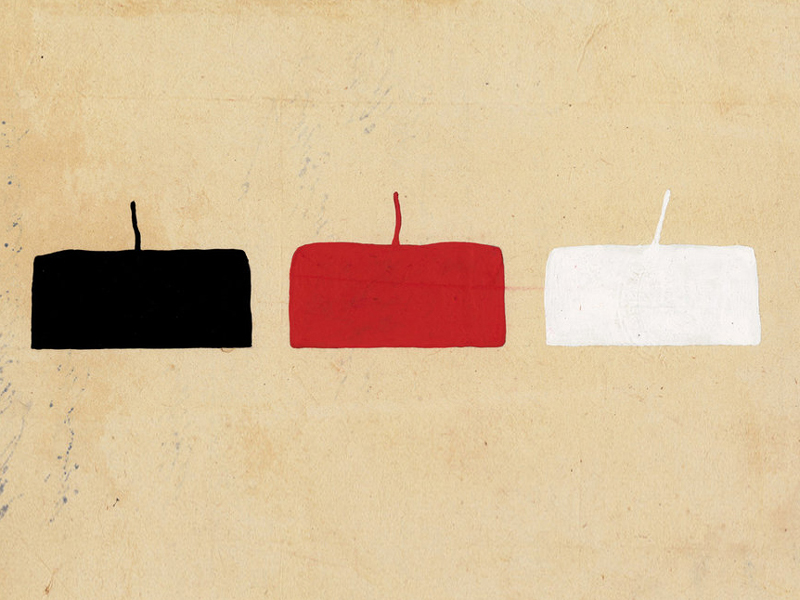

Subsequently, though, I’ve had the pleasure of including works from Franck’s collection in several exhibitions and I feel that some of these images are becoming old friends: the azure field covered with a thousand cattywampus arrows, the coal-black Shiva linga, the eye-like spirals in an oval of yellow, the “image” that is nothing but a square of chalky white enclosed by a vermillion line. I have come to see young artists’ works inspired by these images, drawn to their directness, elegance, and profound lack of posture. Something of the nature of these works has become part of the fabric of the art culture of my community. They guide us like stars we don’t need to go outside to see.

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

May 11, 2023 — It was spring. And then it was not. And now it is again. How far can you throw a ball? What if one could travel along a high arc, across a continent, an ocean? What if you could travel with the ball, see as it might what is above and below? And I wonder what its speed might be? Enough to stay aloft, but slow, not even so fast as a swallow? That was once how a single season felt. Now…

[...]