Diary of a ChambermaidA woman who pursues a lost love affair in disguiseLauren Elkin, Times Literary Supplement

reviews, 12/23/22

Originally published in the December 23–30, 2022 issue.

“On Monday, February 16, 1981”, Sophie Calle begins The Hotel:

I was hired as a temporary chambermaid for three weeks in a Venetian hotel. I was assigned twelve bedrooms on the fourth floor. In the course of my cleaning duties, I examined the personal belongings of the hotel guests and observed, through details, lives which remained unknown to me. On Friday, March 6, the job came to an end.

Calle keeps detailed notes about the people whose rooms she cleans. Who sleeps in which of the twin beds. Who turns the bedside table around so the drawer opens into the wall. Who leaves their suitcases locked. Who wears what kind of pyjamas. What is inside a coat pocket. She empties everything, spreads it out, photographs it. In one room she rescues a pair of shoes from the bin; in others she uses guests’ toiletries, samples chocolates and sips from a glass of Coke.

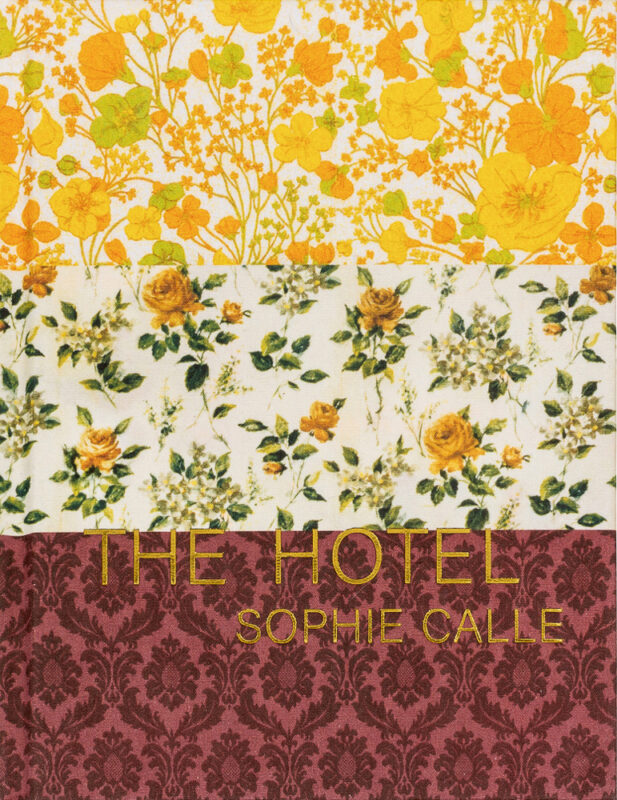

Calle’s now classic work of voyeurism has been reissued by Siglio Press in a beautiful gold-edged edition with a cloth cover that echoes the flocked wallpaper found, one imagines, in the hotel itself. The edition mixes black-and-white photographs – an open window; roof tiles; a desk with a newspaper on it; a washstand in the bedroom – with photographs in bright period colours – yellow wildflower wallpaper/olive green headboard/matching olive phone/multicoloured flower bedspread. It is a knowing mash-up of interior design magazine, arty travel diary and forensic photography.

Nothing here is inadvertent. “Taking a photograph is an act of ‘choosing’”, Janet Hand writes in a 2005 essay on Calle’s work. “Calle’s photographs equate ‘choosing’ with ‘clicking’ a camera as an instantaneous form of critique.” Because the guests’ belongings are being photographed – and implicitly opened up to critique – The Hotel “issues a level of voyeuristic anxiety”. What are our belongings saying about us, when we’re not there to mitigate their effect?

The first room Calle enters (number 25) has a crumpled pair of men’s pyjamas on the bed. The sight of them “does something to me”, she writes, noting the book the guest is reading (W. Somerset Maugham), the fruit on the windowsill, a travel notebook, which she opens, flicks through, puts down. The next day she opens the closet, takes stock of the clothes, their “subdued” colours (“gray, navy, brown”). By a process of elimination she works out what the man is wearing that day. She photographs his diary, with his “poor, irregular” handwriting. Also his tighty-whities.

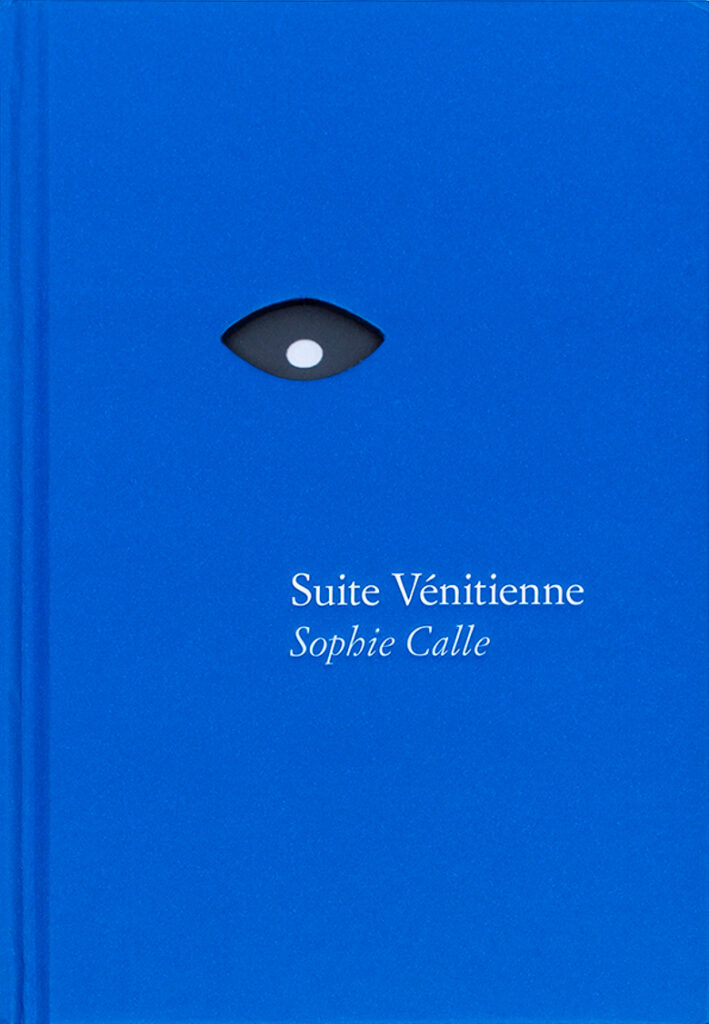

The Casa de Stefani, it so happens, is the hotel Henri B. stayed at in Calle’s previous project, Suite Vénitienne (1980). Following Henri B. to Venice, Calle tracks him through the city, persuading herself that she is in love with him. When he eventually leaves she fantasizes about sleeping in his bed. She tries to reserve his hotel room for the night after his departure, but it is already taken. Returning to the hotel to work as a chambermaid and spy on people so brazenly is a very Calleian move, born of confusing love with obsession. Some of the entries in The Hotel read like little love stories. “I will try to forget him”, she writes after encountering the man in room 25. He is indeed wearing the clothes she had worked out he’d be wearing.

Some of the guests are furtive, putting up the “Do not disturb sign” and leaving it there till they check out. Smart: maybe they realized they had a conceptual artist for a chambermaid. Others seem unaware that they even have a chambermaid; one leaves her dirty underwear in the bathtub with a bloodied sanitary napkin affixed to it. Calle photographs it. Click.

This is a fascinating moment in the book, and I keep coming back to it. Is it, as it reads at first, an example of just how feral people can become when staying in a hotel, a subtle reminder to readers to remember their manners during their next stay somewhere? Or is it a feminist gesture, a comment on the distaste we’ve been conditioned to feel at the sight of period blood, a refusal to see it as anything other than a normal human secretion, the napkin no different from a used tissue? Is there judgement in Calle’s photograph, and if so, who is being judged?

Calle asks the viewer to consider the hotel room as a hybrid space, private and public at the same time; we think we are away from the world, but the world still intrudes on the hotel room, at the very least to clean it. Calle’s project isn’t explicitly about labour – unlike, for example, the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles (for a time the artist in residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation), who in “Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Inside” (July 23, 1973) cleaned the floor of the Wadsworth Atheneum, turning the low-paid maintenance work necessary to keep such sites functioning into an artwork equivalent to those on the wall. But, like the imprint the hotel guest’s body leaves behind on the bed, the invisible chambermaid makes her presence felt: in the unwrapped cake of soap in the dish, the new towels on the rail, the magic turndown at the end of the day.

The Hotel brings to mind Joan Didion’s list of things “To Pack and Wear” (first published in 1979, which makes me think Calle probably read it). In Didion’s case it is the writer (a proto-influencer) who has invited us in: her suitcase is arranged for observation, made orderly and attractive (excuse me while I search for “vintage 1970s leotard” on eBay so I can dress like Didion); and she has, perhaps, left out the things she doesn’t want us to know she packs. Indeed, she goes on to account for one thing that isn’t on the list – a watch.

In other words I had skirts, jerseys, leotards, pullover sweater, shoes, stockings, bra, nightgown, robe, slippers, cigarettes, bourbon, shampoo, toothbrush and paste, Basis soap, razor, deodorant, aspirin, prescriptions, Tampax, face cream, powder, baby oil, mohair throw, typewriter, legal pads, pens, files and a house key, but I didn’t know what time it was.

This list is also about work; we know Didion will be working as a writer wherever she goes. (“This is a list which was taped inside my closet door in Hollywood during those years when I was reporting more or less steadily. The list enabled me to pack, without thinking, for any piece I was likely to do.”) But we know nothing about the invisible labour that makes her work possible. We do not know who will be cleaning her hotel room and what they will make of her belongings; we do not know how she will behave in these hotels, whether she will leave her dirty underwear in the bath.

Here is one of Calle’s lists, the contents of room 24 between March 2 and March 5:

The first things I notice are the books on the table. Alain Gerber’s La couleur orange and a French- Italian dictionary. In the closet: the usual clothes of an ordinary couple, photographic equipment in a camera case, an empty suitcase. The drawer is stuffed with handkerchiefs, medications for a deficient pancreas, and Caporal Gauloises cigarettes.

I empty the handbag on the floor: sugar cubes, Tampax, pink lipstick, postal orders made out to Paulette B., old tickets for a Xenakis concert, and a diary. On the first page I read, “In the event of my death, everything I own will go to Mr. François G. exclusively,” signed “Paulette B.” in a childish, touching handwriting. Under the heading “Notes,” the number 23485.69, the address of a rest home in Versailles, a sentence — “between the age of one year to eighteen months, a young chamois goat is called an ‘éterlou’” — plus a quote from Malraux I find hard to decipher.

But perhaps this too-detailed sketch cautions us against taking Calle too literally at her word. The photographs in Suite Vénitienne, for instance, are a re-creation of a man who could have been, but was not, Henri B. And – as Calle told the Swiss art historian Bice Curiger – one of the rooms in The Hotel is not one she observed during her time as a chambermaid, but one she filled with belongings she herself had sourced, with “what I would have wished to find”. Once we know this (but really we should have suspected it from the start), the amateur ethnography starts to look more like another playful autobiography in a career abounding in them. In Doubles-jeux (1998; a double entendre in French), Calle herself enacts for the camera a series of games that the novelist Paul Auster created for a character based on Calle in his 1992 novel Leviathan.

Forty years in from The Hotel, Calle is still writing playful autobiography set in hotels. Her latest project, Les Fantômes d’Orsay (at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris earlier this year), and its accompanying catalogue, The Elevator Resides in 501, draws on the time between 1978 and 1981 (the period during which Calle made Suite Vénitienne), when she squatted in the abandoned Hôtel d’Orsay, then part of the Gare d’Orsay and now absorbed into the upper floors of the museum.

At the end of 1978, Calle tells us in a fairy-tale preamble, she was idly walking along the banks of the Seine when she noticed an old wooden door in the side of the Gare d’Orsay. “Instinctively, or out of habit, I gave it a push. The door opened.” The hotel had been abandoned for five years. She moves into it – into room 501, to be precise – haunting it like a ghostly guest, gathering the enamelled room numbers, twirling in the ballroom, photographing it.

Filled with the pictures Calle took while she was there – peeling plaster and wallpaper, empty, shadowy hallways, disused pipes, piles of dusty blankets – The Elevator Resides in Room 501 is co-written with the archaeologist Jean-Paul Demoule and structured by two narratives: one is a straightforward account of the images; the other appears to be some kind of field report that looks back on the images from hundreds of years in the future and tries to work out what they might mean. The fact-based, detective-style narrative of The Hotel here gives way to something closer to science fiction. Examining a photograph of two armchairs in an abandoned hallway, the narrator describes them as thrones; they suggest “the existence of a royal couple”, “the king (or emperor) Oddo, who is often mentioned in the archives and whose feminine consort was, without a doubt the queen (or empress?) Odda.” In what the straight narrative identifies as the staff quarters, a series of photographs of pin-up girls is taken in the speculative narrative to be “portraits of the various manifestations of Oddo”, found on the highest “and therefore undoubtedly the most prestigious floor”. The black box on the wall may have been used “as a musical instrument during ceremonies”. It is a knowing wink at how little archaeologists actually have to go on when they construct their narratives of the past, and at how often they must get it wrong. Oddo, we learn in the straight narrative, is the name of the hotel’s handyman; the armchairs indicate that this is a luxury hotel; the black box on the wall is a telephone.

In one section there is speculation about the original use of a “heap of small red pieces of red metal marked with white numbers”. Were these tokens in a game of chance, “blindly selected from a bag by each player, one at a time, and thrown into the middle”? This might explain why some of them appeared damaged. Or perhaps they were part of a game of divination, or the chips from a lottery. “A still more unlikely hypothesis”, the future ethnographer concedes, “might be that the plates bear the room numbers of a hotel that has disappeared”.

At the address Calle gives for the Casa de Stefani in Venice – Calle del Traghetto 2786 – there is apparently a hotel called the Locanda San Barnaba, for which there are no dates available, not this week, not next week, not six months from now. I can find no evidence that anything like the Casa de Stefani existed at all, except in Calle’s project, and in a sales listing from the Lempertz auction house in Cologne of five felt-tip pen-and-paper works from the 1980s by the American conceptual artist James Lee Byers, consisting of the words “JLB Casa Stefani Venice” on headed notepaper. Except for this corroboration by Byers, I would be tempted to suggest that the hotel in The Hotel is made up — that Sophie Calle is as skilled a novelist as Auster, if not more so, in her ability to make us mistake fiction for history.

Lauren Elkin’s next book, Art Monsters: Unruly bodies in feminist art, will be published next year.

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

April 11, 2024 — The spring peepers have thawed (these little frogs freeze in winter) and now, unabashedly randy, they chirp. At first there was one, then two, and now it sounds like thousands. Two days ago, when it was truly spring, their adamantine chorus was almost deafening (we closed the windows to simply think!). Siglio has relocated to a lush, thriving hollow at the furthest most edge of the Berkshires after two years of peripatetics, sans library—which is now unpacked in a less than Benjaminian manner (little time to contemplate—our urgency in getting books on shelves mirrored the peepers need to mate). The first few months of 2024 were almost unendurable, but we’re home, spring is here, and there are books to made. We are singing!

[...]