The Alchemy of the BorderTroy Montes-Michie in Conversation with Brent Hayes Edwards

excerpts, 10/06/22

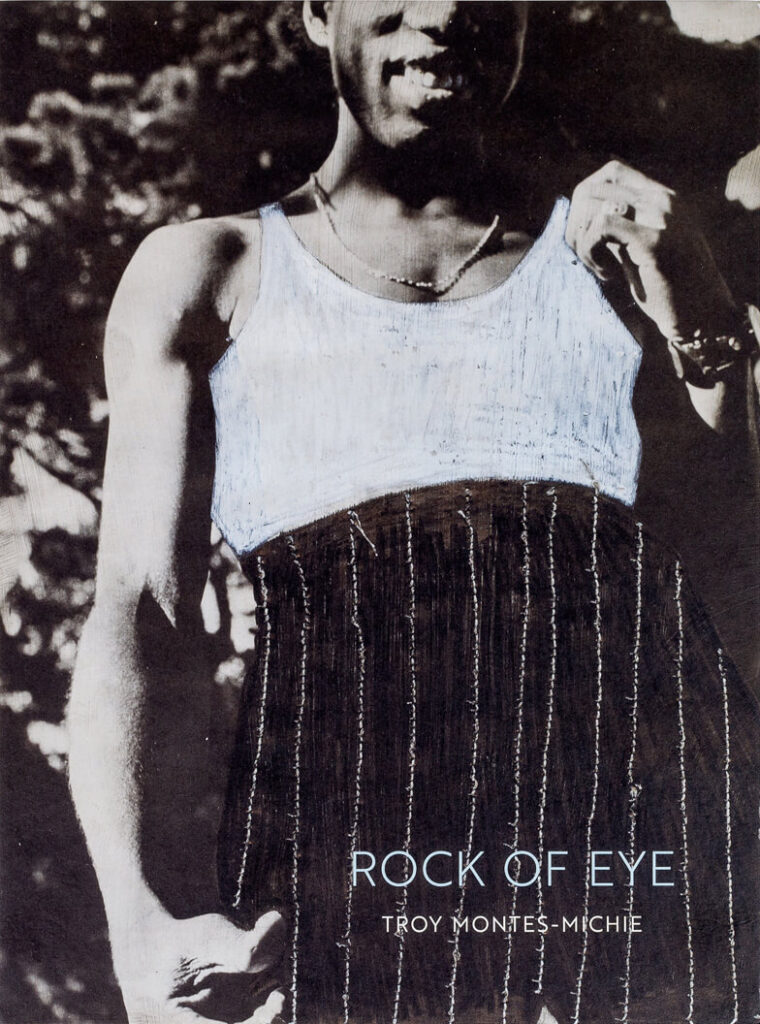

From Rock of Eye by Troy Montes-Michie, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2021. All rights reserved. © 2021 Troy Montes-Michie and Brent Hayes Edwards.

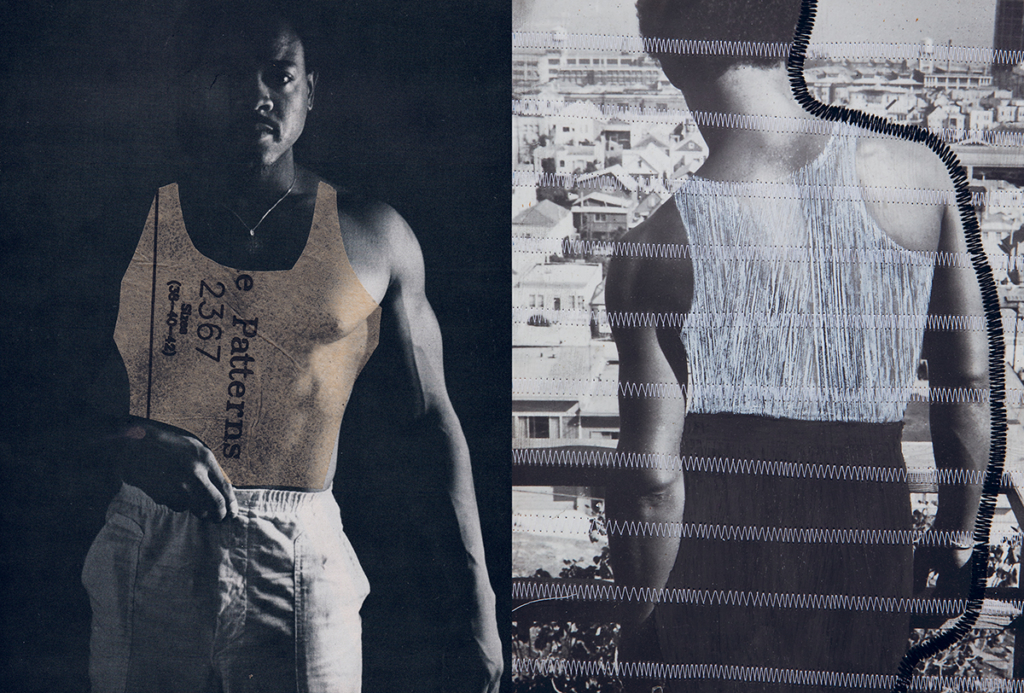

detail from Rock of Eye

Brent Hayes Edwards

There are many ways to think about the idea of a border: as a political frontier, as a geographic demarcation, as a figure for division or separation. But I wanted to start by asking you to talk about the border as a lived experience, growing up in El Paso. How did that atmosphere shape your sensibility as an artist?

Troy Montes-Michie

I’ve come to think of it as my first experience with the language of collage. The whole environment is an amalgam: two very separate cultures colliding on every level. It really is a kind of third space, a third territory, neither Mexico nor the United States, and yet it contains elements of both. Which is akin to the language of collage, a dialogue that forms out of these disparate elements put next to each other.

BHE

Does it feel like things are blurring into each other, or instead like two distinct worlds in juxtaposition?

TMM

Sometimes it feels fluid, a sort of overlapping, an easy back-and-forth: moving between English and Spanish and a combination of visual signifiers from both Mexican and American culture.

But there is a constant reminder of the border wall that runs along the Rio Grande. In certain vicinities, there are check points and you have to confirm your citizenship. The distinction of nationality emanates even though residents of both cities move regularly between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez. For me, all this was normal. I didn’t know anything else. The first time I traveled to the East Coast was to attend the Yale Norfolk School of Art, a six-week undergraduate summer residency program. I remember driving with some other students to neighboring states and being surprised by the absence of state-line checkpoints. I didn’t realize until then that I was raised in an environment of high surveillance. Around that time, I came across Gloria Anzaldúa’s book Borderlands/La Frontera, which I found striking in the way it accurately captures the essence and complexity of border identity.

BHE

I was teaching Anzaldúa last month. I’m always fascinated by the bilingual strategy of that book: she switches between English and Spanish, but most of the time she doesn’t translate. So, if you don’t know one of the languages, those sentences remain opaque. If you’re monolingual, it creates a kind of partition—a feeling of exclusion. That’s another way to think about the border: as mutual opacity. You might not understand everything.

It makes me think of the way so much of your work is divided up into sections, regions, grids. At times the parts seem to speak to or echo off each other, but often there’s a discontinuity. There’s one thing going on over here and, three feet away on the canvas, something very different is happening. So the border isn’t just everything flowing together, but also that sensation of multiple areas of action that are not transparent to each other.

TMM

I can definitely see that. The grids started first as a reference to fabric when magnified, which informed my interest in paper-weaving. But then I started to think about the parameters of shape—the way that parts of the artwork could suggest territories. And being multi-ethnic myself, I do think there’s a kind of opacity that happens. It’s also there with the history of the zoot suit. That’s one of the things I kept asking myself as I made the work. Why was the zoot suiters’ self-fashioning such a threat? Why was it seen as so outlandish? Why did it make them a target? Their parents wanted them to assimilate to American culture. But these young Mexican Americans insisted on making their own status with the creation of Pachuco subculture, a mixture of identities—drawing upon the music and style of jazz coming out of Harlem with Cab Calloway, but also transforming it through the lens of location and border culture.

• • •

BHE

With all the layers and intricacy of your work, there are portals and apertures that draw you in—and of course, as a viewer, part of what you’re enticed by is the expectation of the “reveal.” But when that happens, when you get up close, you notice that the collages are less explicit than you think they’re going to be. Sometimes you even paint over their crotches or add a tank top. There’s a kind of concealment in the work—even a kind of care.

TMM

Yes. Collage in my practice is primarily used as a tool for disruption. For me the cut and juxtaposition are shifts that disrupt the objectified figure in an image, who was poised and directed in the historical circumstance of white gay consumption.

BHE

It’s a fraught strategy because collage has a parasitical relationship to photography. If you’re cutting and repurposing a photo, you’re relying on that original gaze and the perspective that’s embedded in it. In a sense, you’re looking through the eyes of the white photographers who were eroticizing those Black and brown bodies. When you cut out pieces and reposition parts of bodies, you seem to be trying to disrupt the very gaze that you’re inside of. It’s as though you’re cutting and pasting your way out of that white gaze. It’s one of the things I really appreciate about the work. The erotic charge is still there, but the collage almost proliferates it, makes it go in more directions, because the bodies are refracted and multiplied, suddenly re-seen from other angles. Not only is the eroticizing gaze disrupted, but it feels like the images are being layered or fractured with other lines of sight.

TMM

Definitely. I think it goes beyond photography and reflects the dual consciousness that people of color endure inside the violent expansiveness of mass-media culture. One is forced to measure oneself through the lens of a culture that glamorizes European standards of beauty and traditions while denouncing what is perceived as “other.” …

Complete interview available in Rock of Eye by Troy Montes-Michie, Siglio/Rivers/CAAM, 2021.

see also

Books

Rock of EyeEssays by Andrea Andersson and Tina Campt, interview by Brent Hayes Edwards and afterword by Cameron Shaw

Books

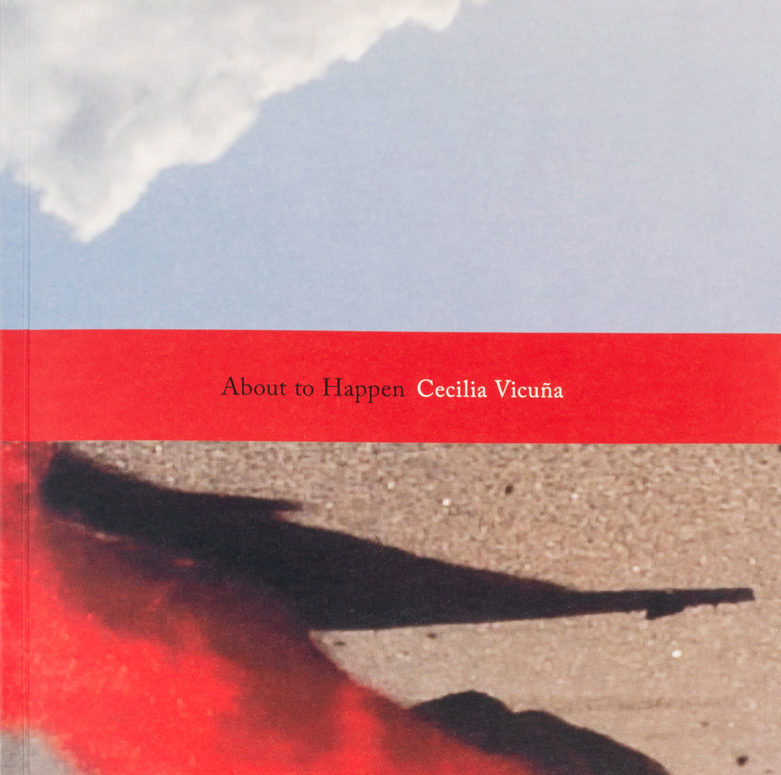

About to HappenEssays by Andrea Andersson, Lucy Lippard and Macarena Gómez-Barris and an interview by Julia Bryan-Wilson

Books

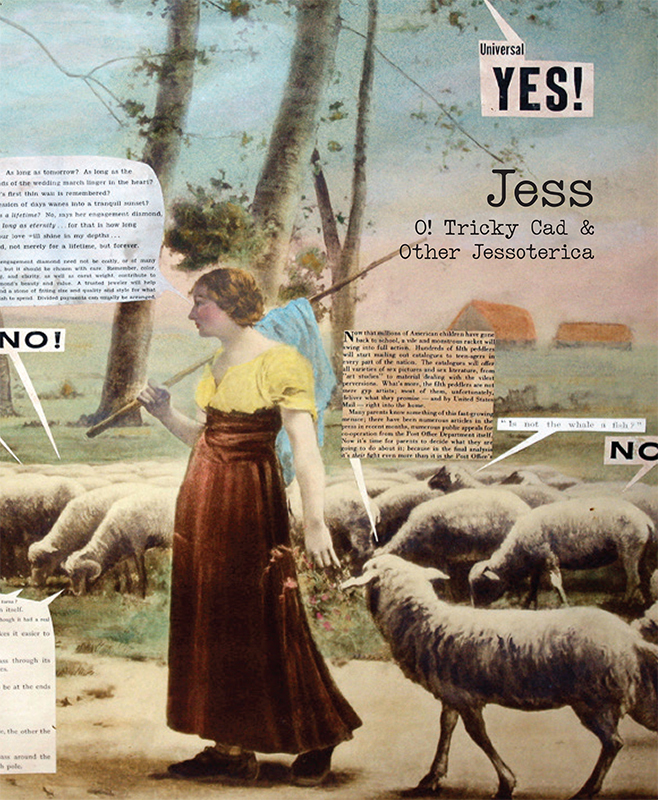

O! Tricky Cad & Other JessotericaEdited by Michael Duncan

✼ consideration:

“Here Comes Kitty: A Comic Opera … achieves the hidden aim of all postmodern work. Namely, befuddling the reader with the dilemma: is this sheer brilliance? Or merely incomprehensible nonsense?”

[...]