A Serpentine AssortmentRay Johnson and Snakes

affinities, 04/15/14

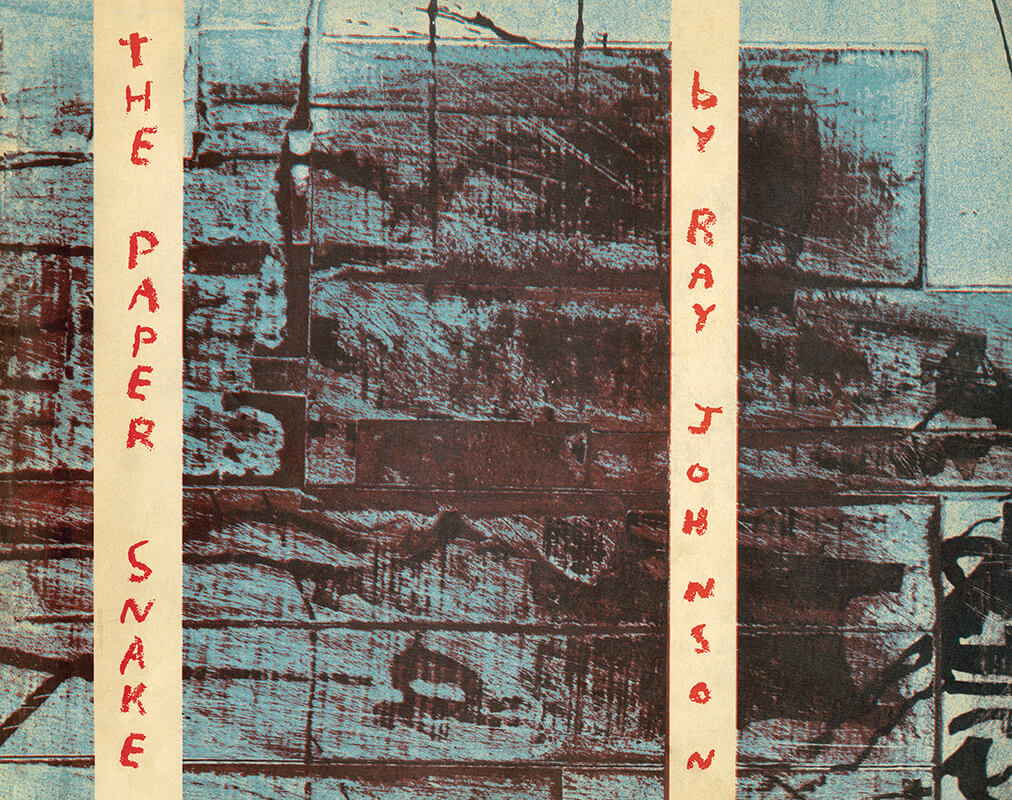

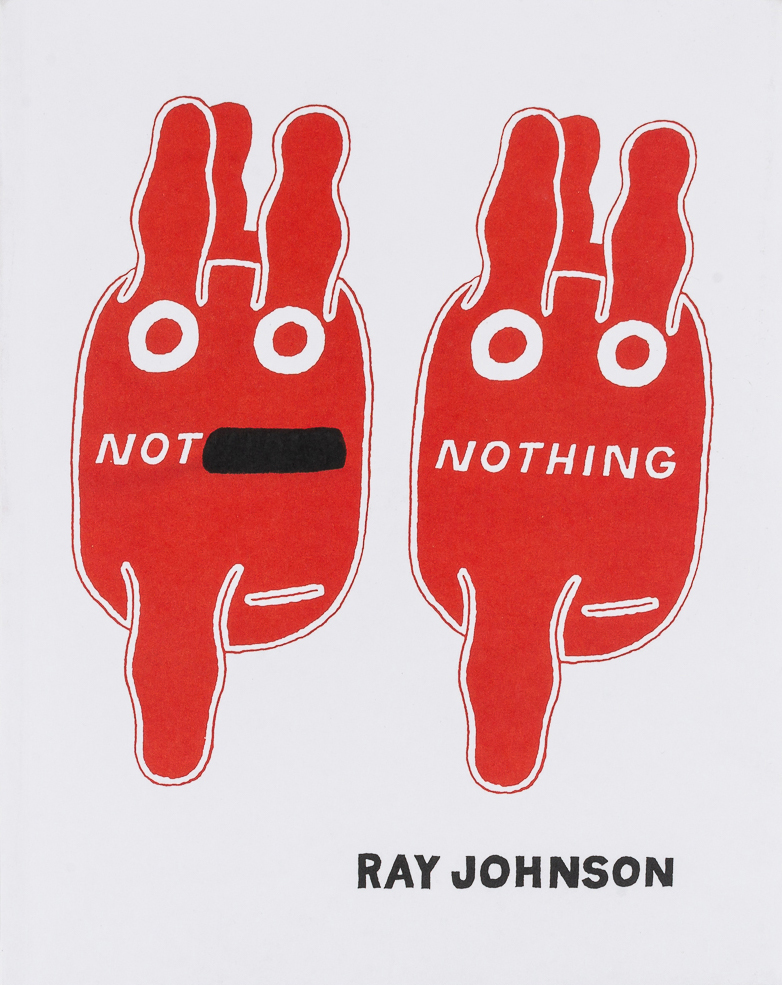

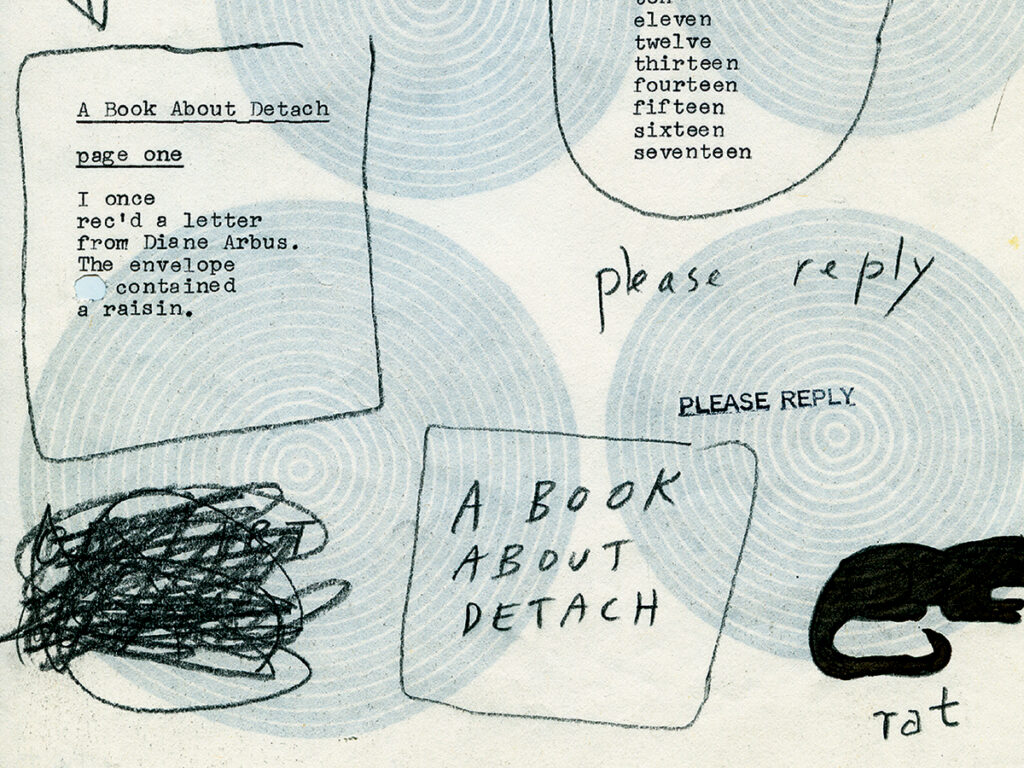

This first blog post in our series on Ray Johnson is inspired by his persistent play with “the snake” in its many forms. “Snakes” are featured (or mentioned) in many of the works in Siglio’s upcoming publication of Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954–1994 and in his artist’s book The Paper Snake by Ray Johnson. In the spirit of this play, collected here are summaries of scientific articles interspersed with some snake-related Johnsonia to suggest all kinds of connections—between species, between the real and the constructed, between word and object. Selected and arranged by Lisa Thorne.

• • •

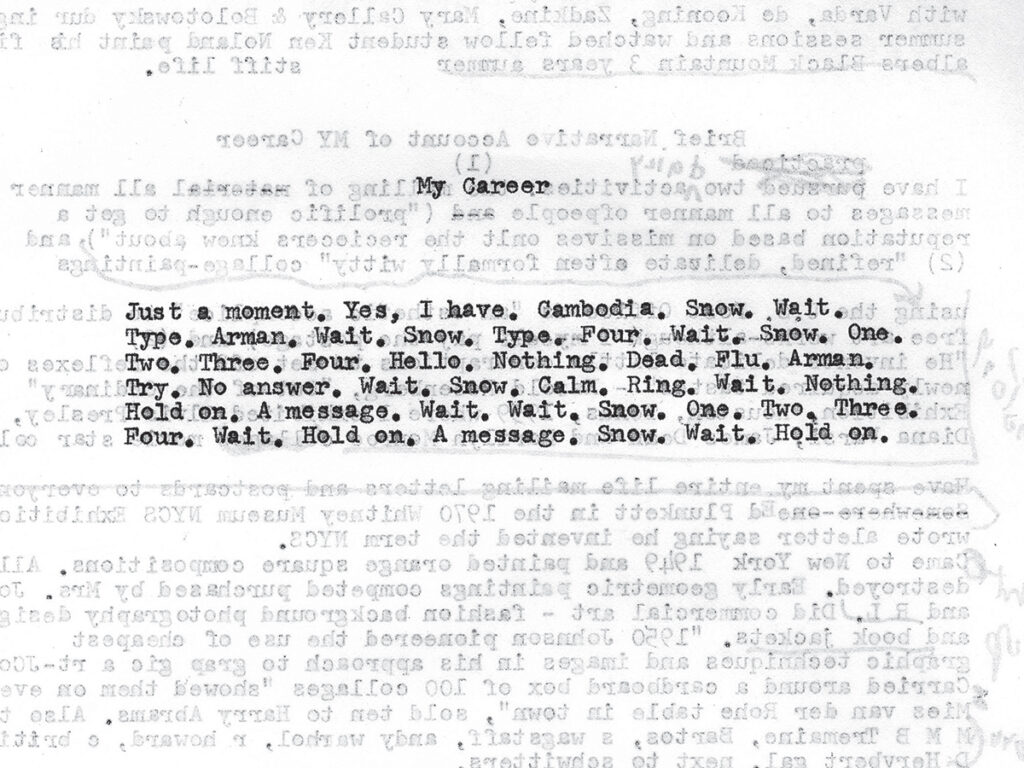

Andy Warhol says my snakes aren’t snakes—they’re worms because they aren’t life size. But some of my snakes are imaginary and inarticulate snakes, and what is life size about inarticulateness?

—Ray Johnson

Quoted in William S. Wilson, introduction, The Paper Snake by Ray Johnson, originally published in 1965 by Something Else Press, reprinted in facsimile by Siglio in 2014.

1.

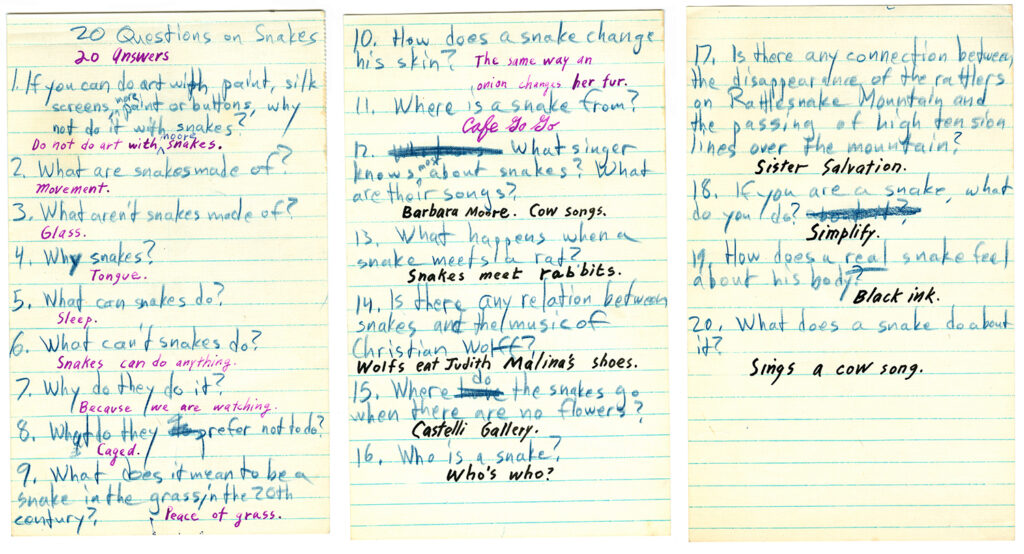

20 Questions on Snakes by Ray Johnson, c. 1980

2.

The Pop Out Effect: Detecting the Snake in the Grass

In this study, participants searched for pictures of snakes distributed among pictures of flowers as well as pictures of flowers distributed among pictures of snakes. The snakes among flowers were located nearly instantly and counted quickly, while the flowers among snakes were detected more slowly as participants had to actively ignore the snake stimuli that were demanding their visual attention. This “pop-out” effect demonstrates that fearful objects such as snakes take over the mind’s focus even when the person is occupied with another task. Moreover, participants who said they are specifically fearful of snakes were able to count the snakes even more quickly, indicating that the pop out effect is stronger when the fearful object is more emotionally provocative.

3.

Snake-Imitating Caterpillars Deter Avian Predators

Many species of caterpillar appear to gain protection from insect-eating birds because they possess eyespots, a pair of conspicuous markings on the body generally thought to resemble the eyes of a predator. Similarly, many caterpillars puff up several body segments when threatened, which may also deter attack because it emphasizes the caterpillar’s eyes and/or allows the caterpillar to more closely resemble a snake’s head. To disentangle the protective value of eyespots and enlarged body segments, researchers in Canada constructed artificial caterpillars and placed them on tree branches in the territories of wild birds. The models of snake-imitating caterpillars were found to have a clear survival advantage over the non-snake-imitating models, even at northern latitudes where there are relatively few arboreal snakes. Neither method of snake mimicry was found to be more effective than the other, and having both eyespots and enlarged body segments did not significantly reduce predation.

4.

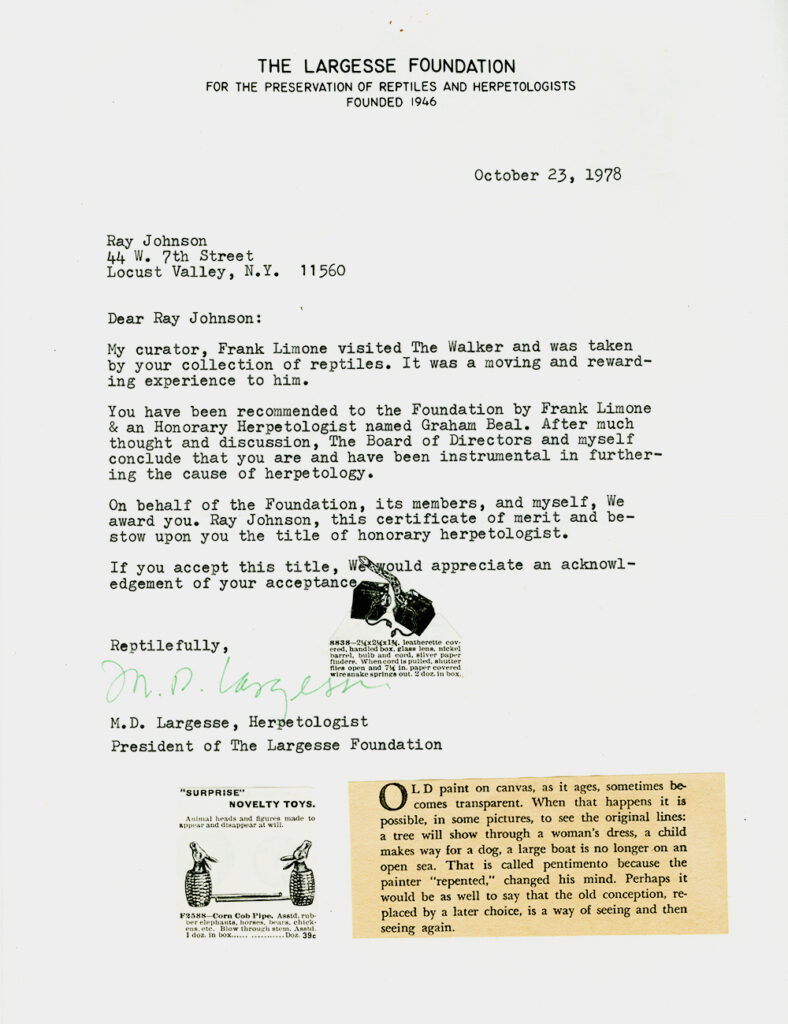

Untitled (Dear Ray Johnson—

from the Largesse Foundation) by Ray Johnson, 1978

5.

Snake Warnings and Snake Searches Among Vervet Monkeys

Vervet monkeys produce distinct vocalizations upon spotting certain types of predators and also react differently when hearing these alarm calls. For example, when a vervet spots a snake, he will produce high-pitched chutters (acoustically distinct from the short tonal “leopard alarm” calls or low-pitched staccato “eagle alarm”) and other monkeys will subsequently scan the ground around them, presumably to locate the encroaching snake. By playing back recordings of the alarms when predators were absent, this study provides further evidence that these reactions are based only on hearing an alarm call, indicating a form of complex communication rarely observed outside of human language. Data also show that infant vervets give snake alarms to various long thin objects, suggesting that predator classification improves with age and experience.

6.

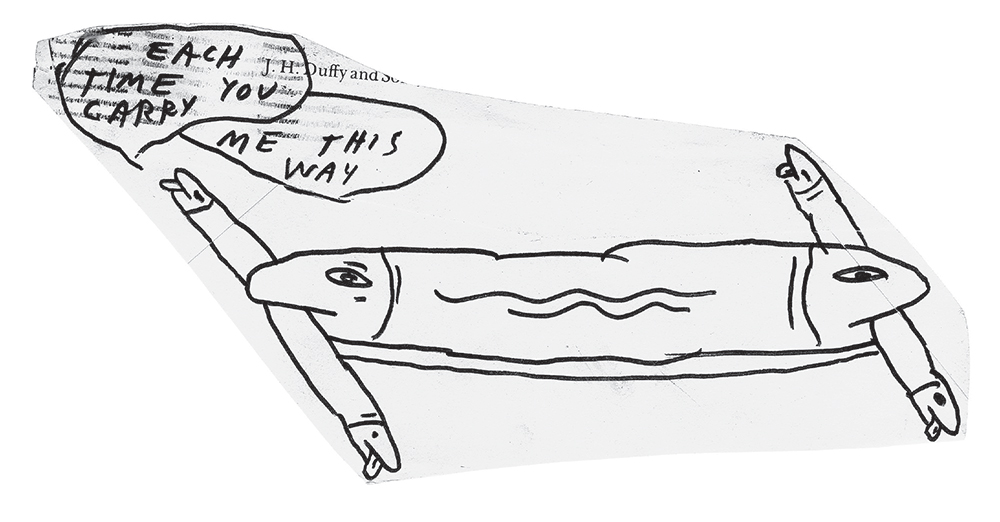

Untitled (Each time you carry me this way)

by Ray Johnson, c. 1986

7.

Testing the Gliding Performance of a Flying Snake

When gliding, the flying snake Chrysopelea paradisi morphs its circular cross-section into a triangular shape by splaying its ribs and flattening its body, which acts to create a lifting surface in the absence of wings. This study aimed to understand the aerodynamic properties of the snake’s shape to determine its contribution to gliding at low velocities. Using an anatomically-similar model, tests showed that this geometry helps the snake glide higher and farther than many other shapes. These aerodynamic characteristics help to explain how the snake can glide at steep angles and over a wide range of angles of attack, although more research on aerial undulation is required to fully understand the gliding performance of flying snakes.

8.

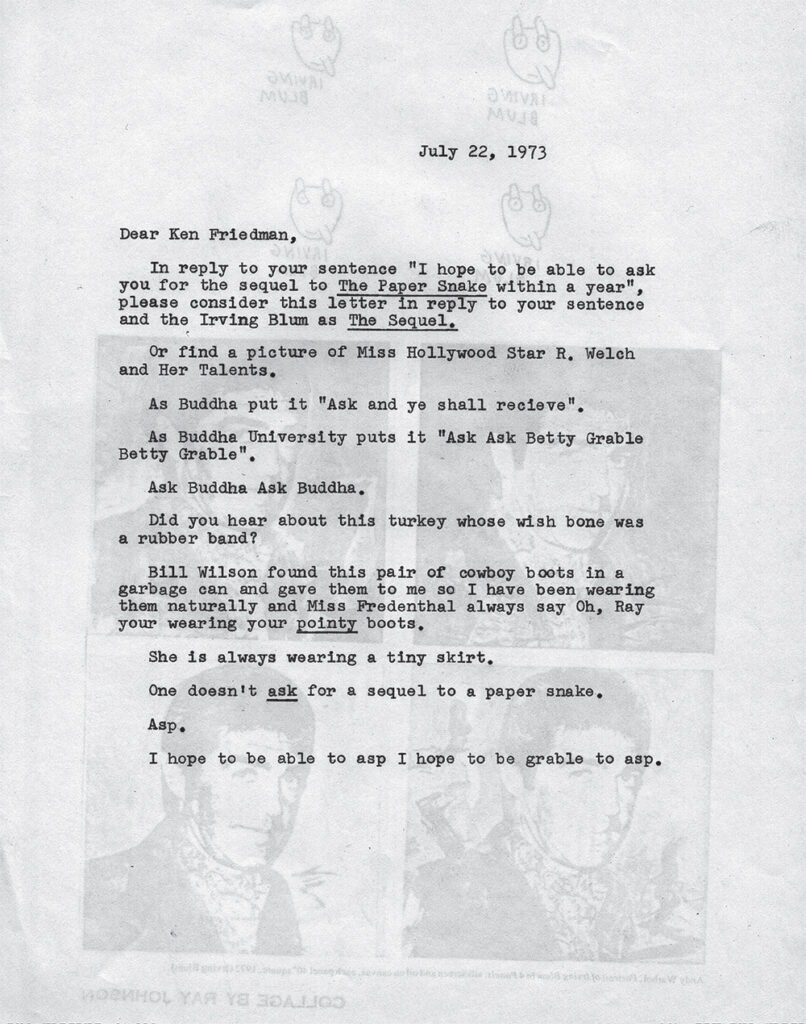

Untitled (Dear Ken Friedman) by Ray Johnson, 1973

footnotes

- “20 Questions About Snakes“ by Ray Johnson, c. 1980. Copyright the Ray Johnson Estate Archives, courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. All rights reserved. Previously unpublished.

- Arne Öhman, Anders Flykt, and Francisco Esteves. “Emotion Drives Attention: Detecting the Snake in the Grass.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 130, no. 3 (2001): 466–478.

- Thomas John Hossie and Thomas N. Sherratt. “Defensive Posture and Eyespots Deter Avian Predators from Attacking Caterpillar Models.” Animal Behaviour 86, no. 2 (2013): 383–389.

- Untitled (Dear Ray Johnson—from the Largesse Foundation) by Ray Johnson, 1978. Copyright the Ray Johnson Estate Archives, courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. All rights reserved. Previously unpublished.

- Robert M. Seyfarth, Dorothy L. Cheney, and Peter Marler. “Monkey Responses to Three Different Alarm Calls: Evidence of Predator Classification and Semantic Communication.” Science 210, no. 4471 (1980): 801–803.

- Untitled (Each time you carry me this way) by Ray Johnson, c. 1986. Copyright the Ray Johnson Estate Archives, courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. All rights reserved. Published in Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954-1994, edited by Elizabeth Zuba (Siglio, 2014).

- Daniel Holden, John J. Socha, Nicholas D. Cardwell, and Pavlos P. Vlachos. “Aerodynamics of the Flying Snake Chrysopelea paradisi: How a Bluff Body Cross-Sectional Shape Contributes to Gliding Performance.” Journal of Experimental Biology 217, no. 3 (2014): 382–394.

- Untitled (Dear Ken Friedman), 1973. Copyright the Ray Johnson Estate Archives, courtesy Richard L. Feigen & Co. All rights reserved. Published in Not Nothing: Selected Writings by Ray Johnson, 1954-1994, edited by Elizabeth Zuba (Siglio, 2014).

see also

✼ natalie’s upstate weather report:

May 11, 2023 — It was spring. And then it was not. And now it is again. How far can you throw a ball? What if one could travel along a high arc, across a continent, an ocean? What if you could travel with the ball, see as it might what is above and below? And I wonder what its speed might be? Enough to stay aloft, but slow, not even so fast as a swallow? That was once how a single season felt. Now…

[...]